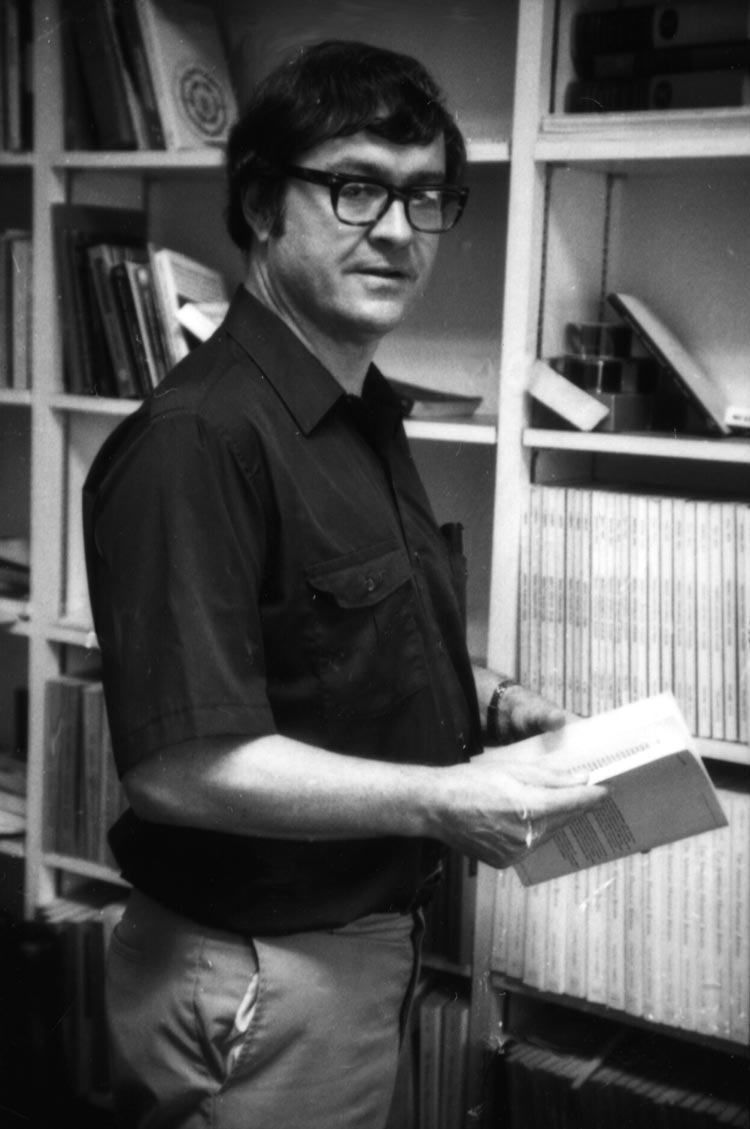

Alexander Sedgwick was one of those University of Virginia faculty members who felt a responsibility – one colleague described it as a calling – to serve UVA in several ways during his long tenure on Grounds.

The former dean of the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences and University Professor Emeritus died July 22 in Charlottesville. A professor in the Corcoran Department of History who specialized in early modern French history, Sedgwick came to UVA in 1963 and stayed for 34 years.

Sedgwick, who earned his Ph.D. from Harvard University after serving in the U.S. Army, chaired UVA’s history department from 1979 to ’85, served as dean of the College from 1985 to ’90, and then served as dean of graduate studies for the next five years. A member of the American Association of University Professors, he was on its national council from 1976 to ’79. He held a University Professorship from 1995 to ’97, and retired as emeritus in 1997.

His scholarship focused on French politics and religion, especially of the 17th-century movement called Jansenism, the subject of his last book, “The Travails of Conscience: The Arnaud Family and the Ancien Régime,” published by Harvard University Press in 1998.

Sedgwick joined the University faculty in 1963, when “there was a lot going on,” his wife, Charlene, recalled.

He came to the University at a turbulent time, said his wife Charlene Sedgwick, who eventually joined the English department faculty. “It was after Massive Resistance, and the schools were opening up as integrated schools. There was a lot going on,” she said, saying they were active with other faculty members, including William Elwood and Paul Gaston, in seeking to improve conditions for African-Americans in Charlottesville and at the University.

In addition, Sedgwick would travel with the late Bill Harbaugh, another UVA history professor, to teach-ins all around the state against the Vietnam War, she said.

As history department chair, he worked with the late Armstead Robinson, a history professor who was establishing the Carter G. Woodson Institute of African-American and African Studies, Charlene said. Retired history professor Joseph Miller, who also helped build the Woodson Institute, said Alex Sedgwick was an important leader at the departmental level as UVA sought to hire faculty in joint appointments with departments such as history and the institute’s innovative fields of African-American and African studies.

“These were joint department/institute appointments – a significant and not uncontroversial innovation at the time,” Miller said. “… We, including Alex, were dedicated to scholarship and teaching. Hence the importance of buy-ins from the department chairs, who were the trustees of the various disciplines involved.”

When H.C. Erik Midelfort, who counted Sedgwick as one of his dearest friends and colleagues, came to UVA in 1970, they shared scholarship in the same time period in the neighboring countries of France and Germany, the latter of which Midelfort studied.

Sedgwick, whom Midelfort described as well-read, was an early advocate of interdisciplinary scholarship. Along with the Woodson Institute, he also supported the University’s new Program in Political and Social Thought, which Midelfort directed for five years.

Sedgwick’s involvement with the American Association of University Professors was very important during the 1980s, when academia was struggling to become more diverse and inclusive. He helped in treating faculty and students fairly, Midelfort said. The organization set standards for hiring, tenure and promotion.

“Alex was an effective spokesman for broader academic concerns that he carried from the chair’s office to the dean’s office,” he said. “I think he saw it as a calling – to deal with larger issues than just in the department, that it was important to have someone in leadership to guide the University in humane and fair practices.”

Charlene Sedgwick mentioned that her husband was supportive of women in academia, knowing the situation so well through their experience. Although they both studied history, nepotism policy prohibited her from being hired in the same department. After filling in to teach a course in the English department, she switched topics and later directed the department’s program in academic writing.

Mary B. McKinley, French professor emeritus and former chair of that department, remembered, “Alex was always very kind to me from the time I arrived here, a young assistant professor and one of the few women on the faculty,” she said. “He expressed interest in my research, but he also showed me the quiet sense of humor that I later had many opportunities to appreciate.”

Gordon Stewart, an association dean who worked with Sedgwick in Arts & Sciences, lauded his concern for others and commitment to the University.

“Alex stood out above all as a human being,” Stewart said, “considerate of all and ready to go to bat for students and faculty alike. I count Alex among those colleagues who for me have always defined the best of the University of Virginia.”

Charles McCurdy, an emeritus professor of history and law, remembers Sedgwick as “a fine scholar and a good manager of people.”

McCurdy praised Sedgwick’s work as chair of the department. “He was a terrific department chair, and a good listener,” McCurdy said. “Every meeting was well-run and decisions were made by consensus. So they made him a dean.” At that time in the 1980s, Arts & Sciences had a dean of the College – the post Sedgwick held – as well as dean of the faculty.

Sedgwick first hired John “Frank” Papovich on an interim basis in the Arts & Sciences office and then into a full-time position as an association dean.

Papovich recently retired and a reception for him was scheduled on what turned out to be several days after Sedgwick’s death, so he shared his reminiscences with the group gathered there. “He was very kind, and he took great concern with my professional development,” Papovich said. “He helped me in ways I didn’t even know I needed to be mentored.”

Beyond his duties, Sedgwick was an enthusiastic Cavalier basketball fan, bringing his whole family to games, his wife said. He also served on the board of Charlottesville’s Tuesday Evening Concert Series, which the couple attended regularly.

Sedgwick hailed from Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he often returned to his ancestral home of an old and storied New England family.

Media Contact

Article Information

August 9, 2017

/content/memoriam-former-arts-sciences-dean-french-historian-alexander-sedgwick