Past is Prologue: How UVA Has Risen to Meet Crises Throughout History

As the world is responding to the spreading COVID-19 pandemic, the University of Virginia is doing its part, from medical research to closing its facilities for the health and safety of its students, faculty and staff. Courses have gone online, students have helped track the virus, and alumni are reaching out to students and each other in this time of uncertainty. The University has postponed Final Exercises and sent students home.

But this is not the first time the University has reacted to a disease or to a major crisis. Typhoid fever has closed the school for periods of time; international wars have elicited response from UVA; and tragedies such as the fire that nearly destroyed the Rotunda and the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks have tested the mettle of the University community, which has always responded with vigor.

This is a look at some of the challenges Hoos have faced over the last two centuries.

Typhoid Fever

The University was closed for two months in 1829 due to an outbreak of typhoid fever, which was blamed at the time on poor cleanliness in the residence halls and in the hotels where the meals were served. Poor ventilation in the rooms and difficulties with the water supply were also blamed.

Dr. Robley Dunglison, who then chaired the faculty, suggested to the Board of Visitors that an infirmary be built or that one of the University’s hotels be converted to an infirmary. He believed that typhus and other contagious diseases were airborne.

“Typhus and, indeed, all contagious diseases require large airy apartments where ventilation can be effected without exposing the sick to unnecessary draughts of air,” he wrote in a letter to the Board of Visitors.

Dunglison proposed that a hotel on the Range be converted to a place where ailing students could be treated, that all students be charged a small fee at the onset of the school term for a nursing fund and that hotelkeepers be required to supply nurses and additional accommodation, to be reimbursed from the student fund. The Board of Visitors considered an 1836 proposal to create a separate space for ailing students, but did not carry it out for lack of funds.

Members of the University’s medical faculty occasionally treated seriously ill students in their pavilions, but this was considered unsatisfactory because they were endangering the health of their own families.

But as the University grew, the Board of Visitors made attempts to protect student health, including upgrading the water system, building a gymnasium near the southern edge of Grounds for students to exercise and practice for athletics in inclement weather, and having health officers inspect student rooms quarterly to assure that they were habitable.

The University’s first infirmary, photographed here in 1901, is now known as Varsity Hall. (Photo courtesy Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

In 1857, the Board of Visitors approved the construction of a health care facility, under the guidance of the University’s health care officers, Dr. James Lawrence Cabell and Dr. John Staige Davis. Designed by architect William A. Pratt, the infirmary had a unique air handling system designed to bring fresh outside air into each room. It was one of the first infirmaries built for a university and served this role until the construction of the University Hospital at the start of 20th century. The infirmary, which accepted its first patients in the 1858-59 school year, survives today as Varsity Hall.

Typhoid returned in 1857 and five students died between June and November. The Board of Visitors had ordered a thorough cleaning of the University the previous year. In March 1858, the Range rooms were closed after more typhoid cases were reported among students who lived there. In an effort to stem the outbreak, the University improved the room ventilation, removed the livestock from Grounds and inspected cisterns daily, However, 14 more students died and many students left the University; the University closed from the end of March through April 1, after which many students returned and finished their session.

The Civil War

The University remained open during the Civil War, despite low enrollment, with only 46 students enrolled in 1862. Some of the professors acted as advisers to the Confederacy, including Socrates Maupin, a chemistry professor, who consulted the Southern Army on explosives and artillery. The faculty formed its own military unit with antiquated firearms, but it was never deployed in the field. While classes continued at the University, there were few extracurricular activities, such as debating societies and publications.

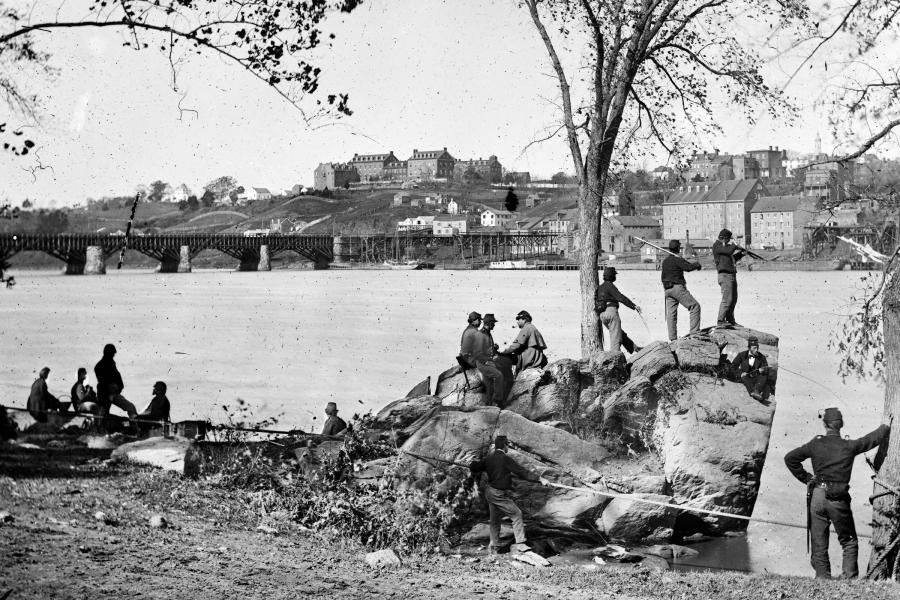

A pontoon bridge at Bull Run, Virginia, 1862. After the First Battle of Bull Run, 1,200 wounded soldiers were brought to Charlottesville; some were treated in student rooms, in the Rotunda and in the infirmary. (Photo courtesy the National Archives)

The Confederate Army established the Charlottesville General Hospital in 1861, with beds in a variety of buildings, including University facilities. After the First Battle of Bull Run, 1,200 wounded soldiers were brought to Charlottesville, and some of them were treated in student rooms, in the Rotunda and in the infirmary. After the May 1862 Port Republic battle, 1,400 were brought to Charlottesville and the Confederate Army insisted all University facilities be used to treat the wounded. Tents on the Lawn handled the overflow of the wounded. University officials complained that this was hampering the University’s operations as they prepared for the next term.

The University authorized the proctor to rent vacant University space for other purposes, with the provision that these tenants vacate the space if students needed the space.

While most of UVA students and alumni were allied with the Confederacy, some sided with the Union cause, including four from the Class of 1861. Included in those enrollment numbers were Union veterans who came to UVA for medical education.

As Union troops advanced on Charlottesville, a delegation of faculty members and local leaders met with Gen. George Armstrong Custer and requested that the University be protected. After four days, Union troops withdrew from Charlottesville, leaving the University intact; after the war, the University enrollment bounced back faster than other Southern universities.

The Rotunda and Annex Fire

Tragedy struck the University on Oct. 27, 1895, when fire destroyed the Rotunda Annex – built on the site of the current plaza to the north of the Rotunda – and heavily damaged the Rotunda. The Annex had been built in the early 1850s, in response to the University’s growth; its five-story structure contained classrooms, offices, laboratories and performance space.

The fire, which was blamed on faulty wiring, started on a Sunday morning in the northwest corner of the Annex, and spread toward the Rotunda, which served as the University’s Library. Students were able to rescue many of the books stored there, as well as Alexander Galt’s life-sized statue of University founder Thomas Jefferson.

After the fire, the faculty met at around 3 p.m. and determined how and where they would hold classes the next day. They used the spaces in the halls of the literary societies, the Temperance Hall, the lecture rooms in the Brooks Hall Museum and the chemical library, as well as using the using the private offices of the professors for smaller classes. Provision was made for all the schools that met in the Annex and the Rotunda, and classes were held that Monday.

World War I

The Great War came early to the University. In 1914, as Europe roiled with war, James R. McConnell, a UVA law student, dropped out of school and traveled to France to join the fight against Germany – three years before the United States entered the conflict.

Working as a volunteer ambulance driver, McConnell was awarded the Croix de Guerre for rescuing a wounded French soldier under fire. With a desire to do more, McConnell and several other ambulance drivers who had been part of the American Field Service created the Lafayette Escadrille, an all-American air squadron flying biplanes against Germany.

In 1914, James R. McConnell, a UVA law student, dropped out of school and traveled to France to join the fight against Germany. (Photo courtesy Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

McConnell was killed on March 19, 1917 – five days after his 30th birthday – in a dogfight with two German fliers, becoming the last American pilot killed in the war before the United States became a combatant.

Less than a week after McConnell’s death, alumni and friends were encouraging University President Edwin A. Alderman to erect a memorial to him. Gutzon Borglum, who sculpted Mt. Rushmore, was commissioned and the statue was unveiled on June 23, 1919. The bronze “winged aviator” now sits on the plaza outside Clemons Library.

As the U.S. entered the war, the University contributed, with many students joining the Reserve Officer Training Corps and holding drills on Grounds.

As in the Civil War, several faculty members became advisers to, and participants in, the military effort. Dr. William H. Goodwin, an associate professor in the School of Medicine, organized a medical field unit, recruiting among alumni to man the unit, which trained under commanding officer Major Julian M. Cabell, an 1886 UVA graduate. Established outside Paris, the hospital cared for 4,700 patients between August 1918 and January 1919.

Roughly 2,500 students and alumni participated in the war; 80 were killed.

1918 Influenza Pandemic

Virginia was hit with the Spanish influenza epidemic in 1918-19. Approximately 326,000 Virginians caught the flu; an estimated 15,679 died.

In Albemarle County, the first death was reported in September 1918; within days, the Charlottesville City Council prohibited large public gatherings and the local schools were closed. The University remained open, although several members of the University community died of the flu, including William Heck, professor of education.

But having the University Hospital proved very beneficial to Charlottesville, where the other local hospital had only about 20 beds, compared to the roughly 200 beds at the University Hospital. Flu victims were treated by hospital personnel. The State Board of Health called for third- and fourth-year medical students to be released from classes to volunteer with flu patients.

World War II

When World War II started for the United States with the attack on U.S. facilities at Pearl Harbor; Marine Lt. Harry Gaver Jr., a 1939 UVA graduate, was among the casualties. Military formations were already common on Grounds, the Selective Service Act having been approved months before. Once war was declared, armed guards patrolled Grounds to protect research facilities and students volunteered for civil defense duties.

By the summer of 1942, the University was operating on a year-round basis as students studied for accelerated degrees. And by 1943, 1,300 of the University’s 1,700 students were enrolled in some form of military-related program.

As with previous wars, the faculty also made its contributions, with around 50 faculty members on leave to serve the war effort. The University contributed to atomic energy and guided missile research, among many classified projects.

Dr. Staige Davis Blackford, an associate professor of medicine, formed the 8th Evacuation Hospital medical unit after convincing School of Medicine Dean Harvey Jordan there was enough personnel to staff the University Hospital and create the military unit. Blackford was assisted by Dr. E. Cato Drash, associate professor of surgery and chief of thoracic surgery. Because Blackford was directed to recruit his own nurses, he prevailed upon Ruth Beery, a former instructor at the School of Nursing, to be the chief nurse of the unit.

Members of UVA’s 8th Evacuation Hospital medical unit in World War II. From left to right: Technician 4th class Dawson, Capt. Guerrant, and Technician 5th class Kavanaugh. (Photo courtesy Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

The University was also provided secret archive for books and manuscripts from the Library of Congress when the government feared invasion.

Enrollment fell during the war, from around 1,700 students in 1942 to 560 in 1944. Students in engineering and the hard sciences were given service deferrals to finish their education, because their knowledge was considered vital to the war effort. Even while continuing their courses, students had to endure the rationing of gasoline, tires, food, sugar, alcohol and cigarettes, through which the general population was also suffering.

Gaver, the UVA alumnus who died at Pearl Harbor, was finally laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery in July 2019.

September 11, 2001

The morning of Sept. 11, 2001, was a warm Tuesday that opened with no hint of what was coming. Students went to classes as normal, but as hijacked airplanes crashed into the Twin Towers in New York City, the Pentagon and a field in Pennsylvania, word spread and the Grounds fell silent.

Elizabeth Simpson, a 2003 political and social thought graduate, heard the news after attending a class in Bryan Hall.

“When we left, Grounds was eerily silent,” Simpson said in 2011. “There was no one around – at 11 a.m. on a Tuesday morning. I felt scared, because I knew something must have happened, but I had no idea what. I ran back to Brown College and found everyone in the lounge, watching TV and crying.”

Some students stood in small clusters, swapping what little information they had. Those with mobile telephones frequently punched in numbers to contact family and friends, only to be frustrated by the overloaded networks. Students gathered around television sets in common areas, constantly seeking updates. Economics professor Kenneth Elzinga, knowing that mobile telephones were less common among students at that time, opened his afternoon lecture in the Chemistry Building by offering his mobile telephone to any student who needed to call and check on someone.

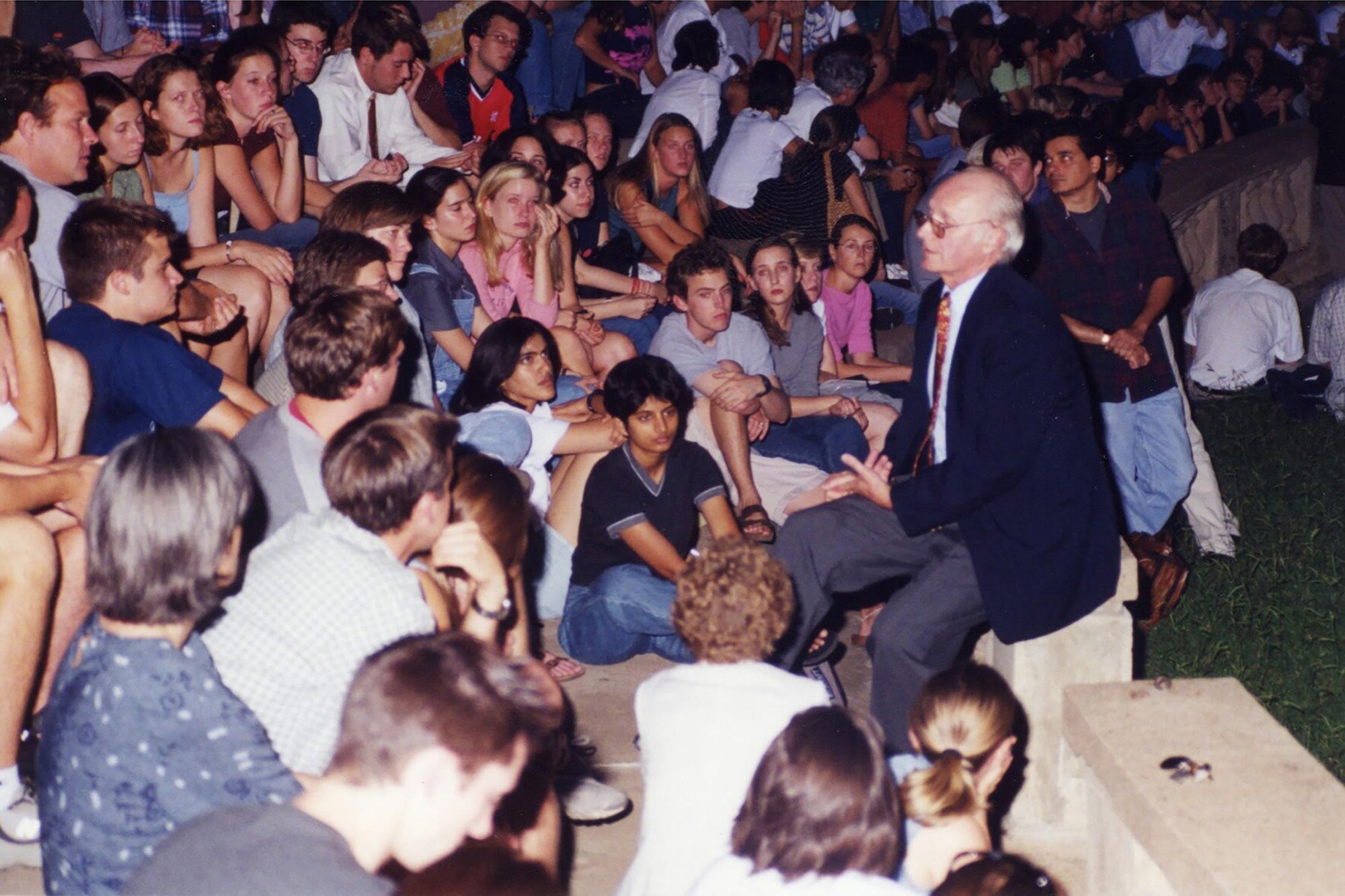

In the wake of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, UVA faculty led a “teach-in” in McIntire Amphitheatre. Here, government and foreign affairs professor William Quandt speaks to students. (Photo by Matt Kelly, University Communications)

Classes were cancelled for several days. Air traffic was halted; students commented how strange it was not to see planes in the sky. Sarah Jobe, who graduated in 2003 with a religious studies degree, organized a candlelight vigil on the Lawn. University Hall hosted a reflection and meditation ceremony, and faculty led a “teach-in” in McIntire Amphitheatre, with speakers including Abdulaziz Sachedina, a professor of religious studies; Peter Ochs, Bronfman Chair of Judaic Studies; politics professor Michael J. Smith; and William Quandt, Edward R. Stettinius Jr. Professor of Government and Foreign Affairs and then-vice provost of international affairs. After problems developed with the sound system, the professors moved into the crowd to talk to groups of students.

Five UVA alumni died in the attacks on the World Trade Center: Glenn Davis Kirwin, class of 1982 and a partner at Cantor Fitzgerald; his co-worker, Douglas Ketcham, class of 1996; A. Todd Ranke, a 1986 graduate of the Darden School of Business, who was with Sandler O’Neill and Partners; Michael J. Cahill, class of 1986, a senior vice president and claims attorney for Marsh & McLennan; and Patrick Sean Murphy, class of 1987 and a vice president at Marsh & McLennan.

The Coronavirus Pandemic

As the University heads into its third full week of online courses, its students spread across the country, the future is uncertain. But it has always been. What is certain is that members of the University community will respond in a positive and active way when confronted with a crisis.

Sources for this story include “Varsity Hall Historic Structures Report” by John G. Waite & Associates, Architects; “Segregation’s Science: The American Eugenics Movement and Virginia – 1900 to 1980,” by Gregory Michael Dorr, M.A., UVA, 1994; “The Alumni Bulletin,” November 1895; “Once and Future Plague - Coming to grips with a pandemic,” Paul Evans, Virginia Magazine; The Influenza Pandemic in Virginia (1918–1919) contributed by Addeane S. Caelleigh, Encyclopedia Virginia; “Formation of the 8th Evacuation Hospital” Historical Collections at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library; “Higher Education Goes to War: The University of Virginia’s Response to World War II” by Jennings L. Wagoner, Jr. and Robert L. Baxter, Jr., Virginia Magazine of History and Biography July 1992; “The Impact of the 1918-1919 Influenza Epidemic,” Stephanie Forrest Barker, 2002 master’s thesis, University of Richmond.

Media Contacts

University News Associate Office of University Communications

mkelly@virginia.edu (434) 924-7291