Talk about shedding light on the unknown: A University of Virginia researcher has developed a way to set biological matter aglow that is 100 times brighter than what scientists commonly use. This offers major advantages to medical researchers who use bioluminescence to track cancer tumors, chart biological processes, understand the functions of genes and develop new drugs to treat and cure disease.

In addition, the improved tool – known as a bioluminescence reporter – shifts that illuminating glow into the red end of the light spectrum. This will let researchers peer deeper into tissues and overcome limitations that have plagued existing approaches. In some applications, the glow can even be seen with the naked eye.

Improving on Nature

Bioluminescence occurs naturally in nature; for example, it’s what gives fireflies their light. Scientists have derived bioluminescent reporters from those blinking beacons of the evening air and also from other natural sources, including beetles and deep-sea shrimp. One recent shrimp derivative proved very useful because it offers a bright blue glow, but scientists thought shifting toward the red end of the spectrum could make it even more powerful. That’s because the blue color interacts strongly with living mammalian tissue, limiting the reporter’s usefulness for deep examination of tissue in the lab setting.

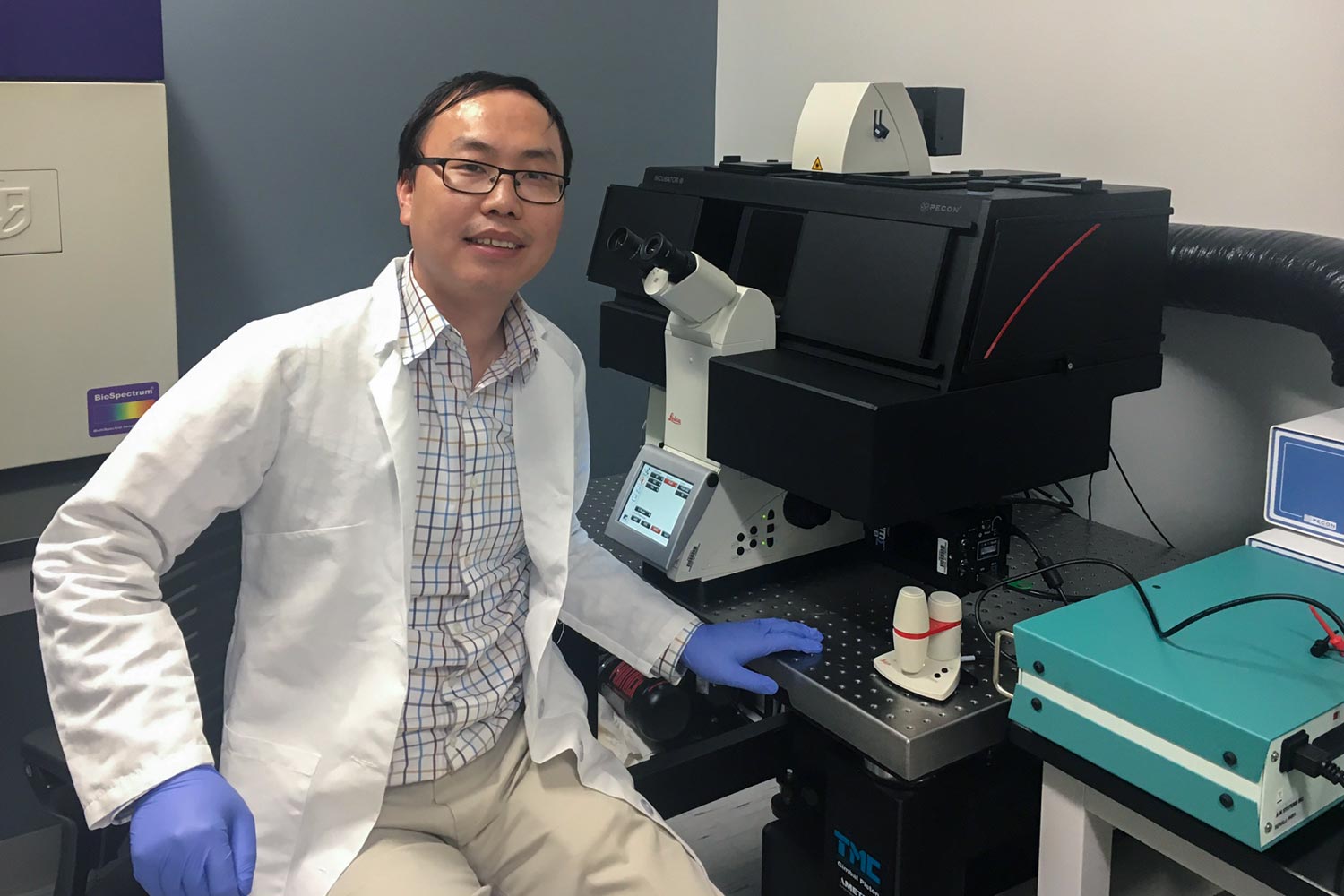

Hui-wang Ai and his team have re-engineered a bioluminescent marker to make it brighter and redder – and thus potentially more useful to researchers. (Photo by Josh Barney, UVA Health System)

Hui-wang Ai, of the Department of Molecular Physiology and Biological Physics in UVA’s School of Medicine, overcame that problem. He and his team re-engineered the reporter and turned the glow redder, creating a potent tool for scientists to use.

“It is approximately 100 times brighter than the most commonly used firefly luciferase, so it is, basically, 100 times more sensitive,” said Ai, who also is affiliated with the Center for Membrane and Cell Physiology and UVA’s Department of Chemistry.

“It means that you can better observe molecules, and if you are tracking, for example, tumor migration, it means that you can track it much more accurately,” he said. “So it’s going to give you much better sensitivity. … Depending on different situations, the improvement is about 15 to 150 times.”

The new reporter is expected have widespread applications – not just in medical research, but in the fields of biology and chemistry as well.

Sharing the News

Ai and his team described their new reporter in the scientific journal Nature Methods. The article authors are Ai, his graduate student Hsien-Wei Yeh, and four former colleagues at the University of California, Riverside: Omran Karmach, Ao Ji, David Carter and Manuela M. Martins-Green.

Ai received the 2017 Chemical Research in Toxicology Young Investigator Award from the American Chemical Society for “applying innovative chemical technologies to the solution of important toxicology problems.”

Media Contact

Article Information

December 15, 2017

/content/powerful-glow-lights-way-medical-breakthroughs