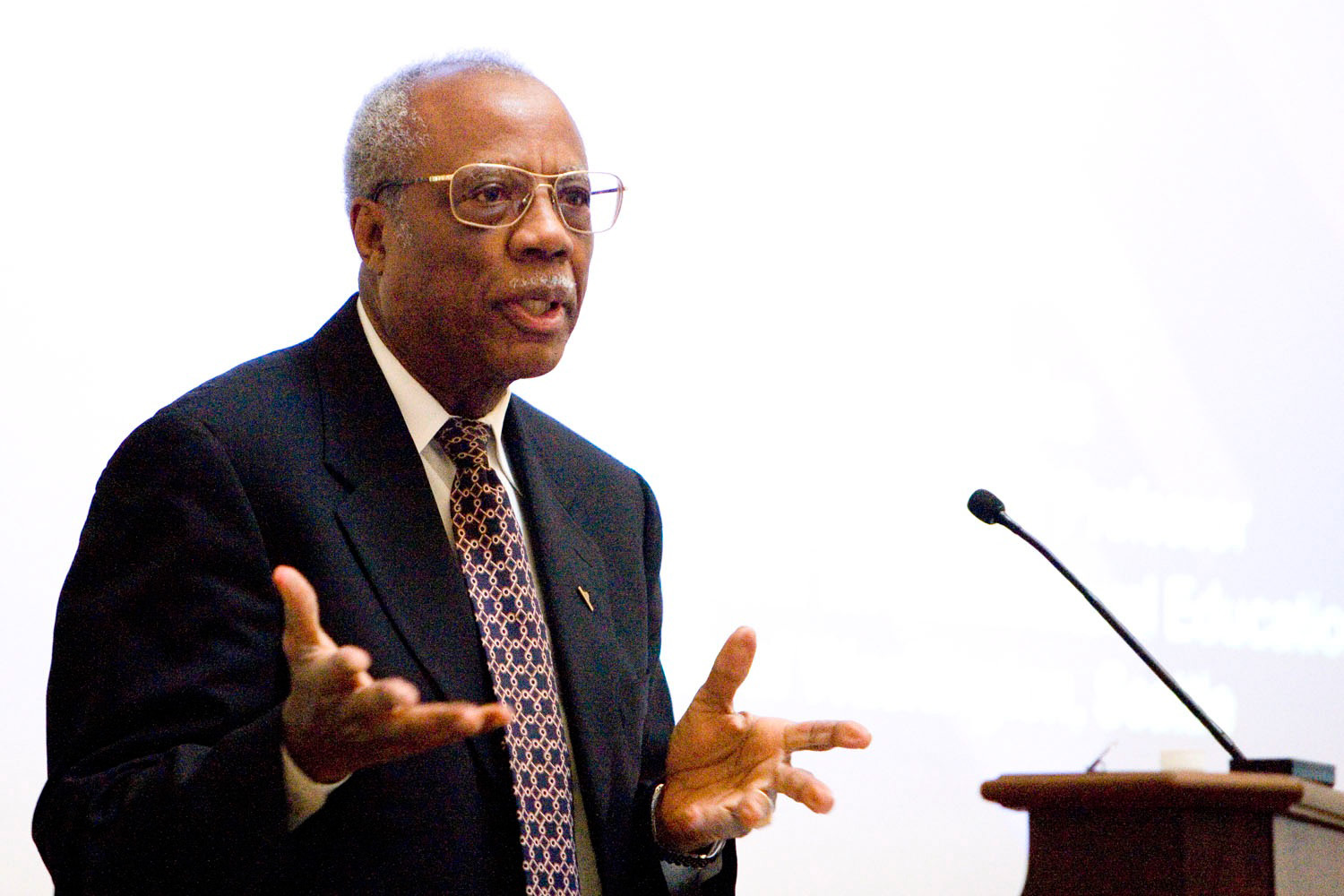

April 4, 2008 — In an increasingly diverse nation and interconnected world, educators must teach students to be global citizens committed to justice for all people, a leading voice in multicultural education told a audience at the annual Walter A. Ridley Distinguished Lecture at the University of Virginia, held April 3 in the Rotunda's Dome Room.

According to James A. Banks, director of the University of Washington's Center for Multicultural Education and the Kerry and Linda Killinger Professor of Diversity Studies, schools across the nation and the world are becoming increasingly diverse due to immigration. He stated there were 191 million migrants worldwide in 2005, and one in every five children in the U.S. is the child of an immigrant. If current trends continue, the number of persons of color in U.S. public schools will equal or exceed the percentage of whites within one to two decades — a situation that is already true in six U.S. states, he noted.

In his lecture, titled "Diversity in America: Challenges and Opportunities for Educating Citizens in Global Times," Banks stressed that this increased diversity requires changes in the way students are taught.

"Because of the way in which people are moving back and forth across national borders today, we must educate students to function across borders, to become global citizens and to develop cosmopolitan values and commitments," Banks said.

He added that this focus on global citizenship requires educators to look beyond a curriculum limited to the "testing and assessment" of basic academic proficiency.

"All students of course need to master basic skills in reading, writing and math," Banks said. "However, these skills are necessary, but not sufficient. I am deeply concerned about an education that is narrowly defined as academic achievement in basic skills. ... Reading, writing and arithmetic are only important if they serve to make students humane."

Banks stated that students should be taught not only "the ability to master, access and use factual knowledge, but also the ability to challenge assumptions, to interrogate and reconstruct knowledge" and learn "to know, to care, and to act," the three goals of global citizenship education. This type of teaching will educate "students' heads, but also their hearts," and create "transformative" citizens who are prepared to take an active role in their society and work for social justice.

The notion of simple patriotism to one nation has become obsolete and our society needs to accept the multi-dimensional nature of diversity, Banks said. A person is not simply a citizen of one country or a member of one ethnic group. Instead, one's identity incorporates a variety of factors, including nation and race, but also factors such as sexual orientation, religion, language and class.

Banks encouraged educators to nurture three levels of identification in their students: cultural, national and global. This will help create a necessary balance between unity and diversity because, according to Banks, "unity without diversity leads to hegemony, and diversity without unity leads to chaos."

This balance between respecting a student's individual cultural background and at the same encouraging national and global identification is what Banks said will ultimately nurture students who are global citizens and answer the question, "How can we educate our students so they grieve for people dying in Darfur and Iraq as much as they do for our own?"

The Ridley Lecture Series honors Walter N. Ridley, U.Va.'s first African-American graduate, who received his doctorate in education from the Curry School in 1953 and went on to a distinguished career in higher education administration. The Curry School, U.Va. Vice President and Chief Officer for Diversity and Equity and the Walter Ridley Scholarship Fund co-sponsor the series.

According to James A. Banks, director of the University of Washington's Center for Multicultural Education and the Kerry and Linda Killinger Professor of Diversity Studies, schools across the nation and the world are becoming increasingly diverse due to immigration. He stated there were 191 million migrants worldwide in 2005, and one in every five children in the U.S. is the child of an immigrant. If current trends continue, the number of persons of color in U.S. public schools will equal or exceed the percentage of whites within one to two decades — a situation that is already true in six U.S. states, he noted.

In his lecture, titled "Diversity in America: Challenges and Opportunities for Educating Citizens in Global Times," Banks stressed that this increased diversity requires changes in the way students are taught.

"Because of the way in which people are moving back and forth across national borders today, we must educate students to function across borders, to become global citizens and to develop cosmopolitan values and commitments," Banks said.

He added that this focus on global citizenship requires educators to look beyond a curriculum limited to the "testing and assessment" of basic academic proficiency.

"All students of course need to master basic skills in reading, writing and math," Banks said. "However, these skills are necessary, but not sufficient. I am deeply concerned about an education that is narrowly defined as academic achievement in basic skills. ... Reading, writing and arithmetic are only important if they serve to make students humane."

Banks stated that students should be taught not only "the ability to master, access and use factual knowledge, but also the ability to challenge assumptions, to interrogate and reconstruct knowledge" and learn "to know, to care, and to act," the three goals of global citizenship education. This type of teaching will educate "students' heads, but also their hearts," and create "transformative" citizens who are prepared to take an active role in their society and work for social justice.

The notion of simple patriotism to one nation has become obsolete and our society needs to accept the multi-dimensional nature of diversity, Banks said. A person is not simply a citizen of one country or a member of one ethnic group. Instead, one's identity incorporates a variety of factors, including nation and race, but also factors such as sexual orientation, religion, language and class.

Banks encouraged educators to nurture three levels of identification in their students: cultural, national and global. This will help create a necessary balance between unity and diversity because, according to Banks, "unity without diversity leads to hegemony, and diversity without unity leads to chaos."

This balance between respecting a student's individual cultural background and at the same encouraging national and global identification is what Banks said will ultimately nurture students who are global citizens and answer the question, "How can we educate our students so they grieve for people dying in Darfur and Iraq as much as they do for our own?"

The Ridley Lecture Series honors Walter N. Ridley, U.Va.'s first African-American graduate, who received his doctorate in education from the Curry School in 1953 and went on to a distinguished career in higher education administration. The Curry School, U.Va. Vice President and Chief Officer for Diversity and Equity and the Walter Ridley Scholarship Fund co-sponsor the series.

— By Catherine Conkle

Media Contact

Article Information

April 4, 2008

/content/professor-james-banks-encourages-educating-students-be-global-citizens-annual-ridley-lecture