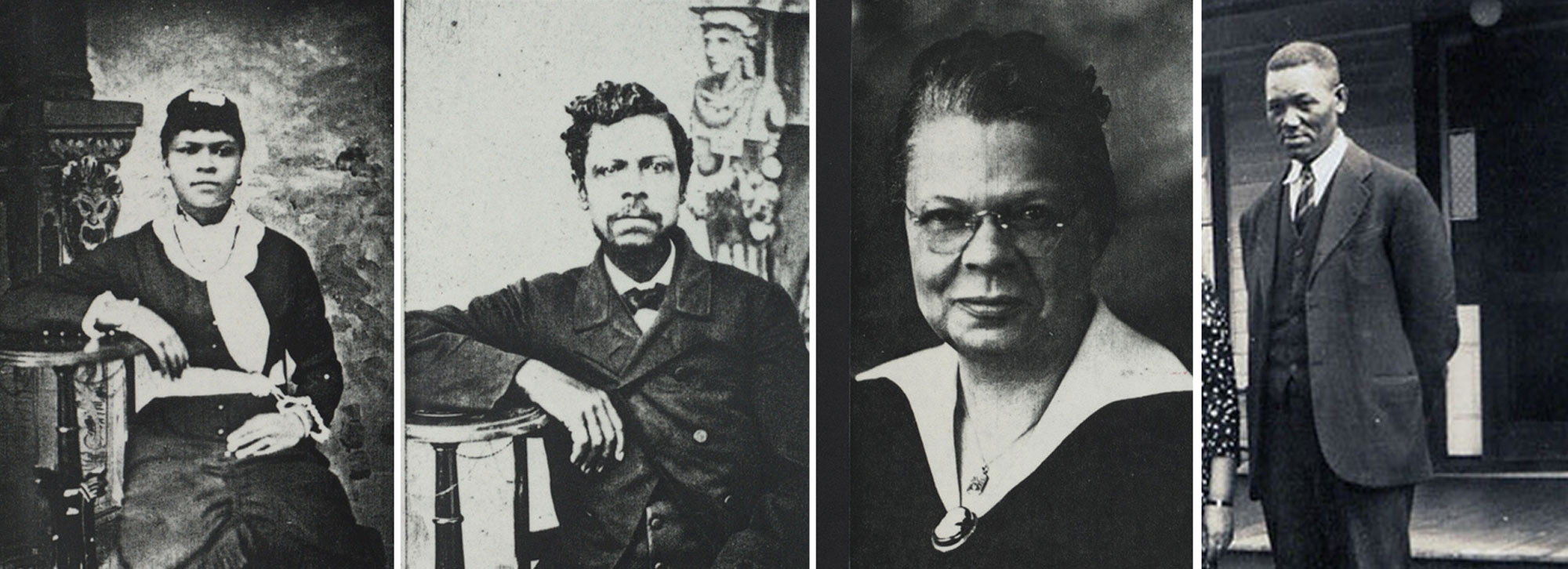

It began in 1870, when Hugh Carr, a recently emancipated Black farmer, paid $100 for 58 acres of land near the intersection of Ivy Creek and the Rivanna River. Carr continued to accumulate land, growing the property to nearly 125 acres. He built a farmhouse and multiple outbuildings and raised seven children with his wife, Texie Mae Hawkins.

Their eldest daughter, Mary, inherited the farm and served as a prominent educator in the African American community, eventually becoming principal of Albemarle Training School – one of the only schools in the area where Black children could continue their education beyond seventh grade.

She, too, added to the farm over the years by buying adjacent pieces of land. Her husband, Conly Greer, was the first Black agricultural extension agent in Albemarle County. He traveled the county by horseback to train other Black farmers in cutting-edge agricultural methods. From 1937 to ’38, he built the large frame demonstration barn that caught Lisa Shutt’s attention so many years later.

“I became fascinated by this place and wanted to preserve and share the legacy of this incredible family, especially with UVA students,” Shutt said. “Most of the people I come across who are deeply invested in the preservation of non-UVA local histories tend to be community members. I want our students to be just as invested in local histories.”

While the City of Charlottesville and Albemarle County own the land and maintain the buildings, the Ivy Creek Foundation helped get the property listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Over the past few years, Susie Farmer, the director of education for the Ivy Creek Foundation, has worked with UVA’s Special Collections Library, where many documents relating to the family and farm are held.

Shutt reached out to Farmer and local historian Alice Cannon to further research the work and teachings of the Carr and Greer families. This past spring, with the permission and support of the Ivy Creek Foundation, including its Descendants’ Committee, Shutt taught a UVA African American Studies seminar, “Engaging Local Histories: River View Farm.”

The class brought undergraduate students to the land, as well as to Special Collections.

“I wanted students to think about what Black communities and Black individuals had to do in order to be successful in time periods where that was made extremely difficult by white power structures,” Shutt said.

“Successful research and preservation are a wildly collaborative effort that calls upon a variety of specialized skills for advancement: genealogy, 3D scanning, archival maintenance, navigation, cataloging, and even re-cataloging,” said Katrina Spencer, librarian for African American and African studies, who helped Shutt’s students with their research. “The work on River View Farm with local community members is a great example of that.”

History Made Real

Students in Shutt’s class hiked the land, learning which areas were used for farming, and explored the barn’s interior. They visited local food scholar Leni Sorensen on her farmstead in Crozet, where, in the tradition of Mary Carr Greer’s food preservation classes, Sorensen taught them how to make and preserve strawberry jam.

The students were trained to be barn docents, giving them the ability to lead tours of the entire farm. And Shutt reached out to Spencer, who is also the Library’s subject liaison to the Woodson Institute, to help guide her students through the Carr family papers in Special Collections.

Spencer prepared an instructional session for Shutt’s students and enlisted Jean Cooper, the library’s principal cataloger and genealogical resources specialist, to assist. The two tailored the session, held in Clemons Library, to the topics on which students were focusing: Black education and Black land ownership.

The librarians gave an overview of how to identify primary sources, how to search databases and access Special Collections, and how to interpret census data, with a deep dive into genealogy, a specialty of Cooper’s.