Q. That means you’ve been reading Whitman for how long?

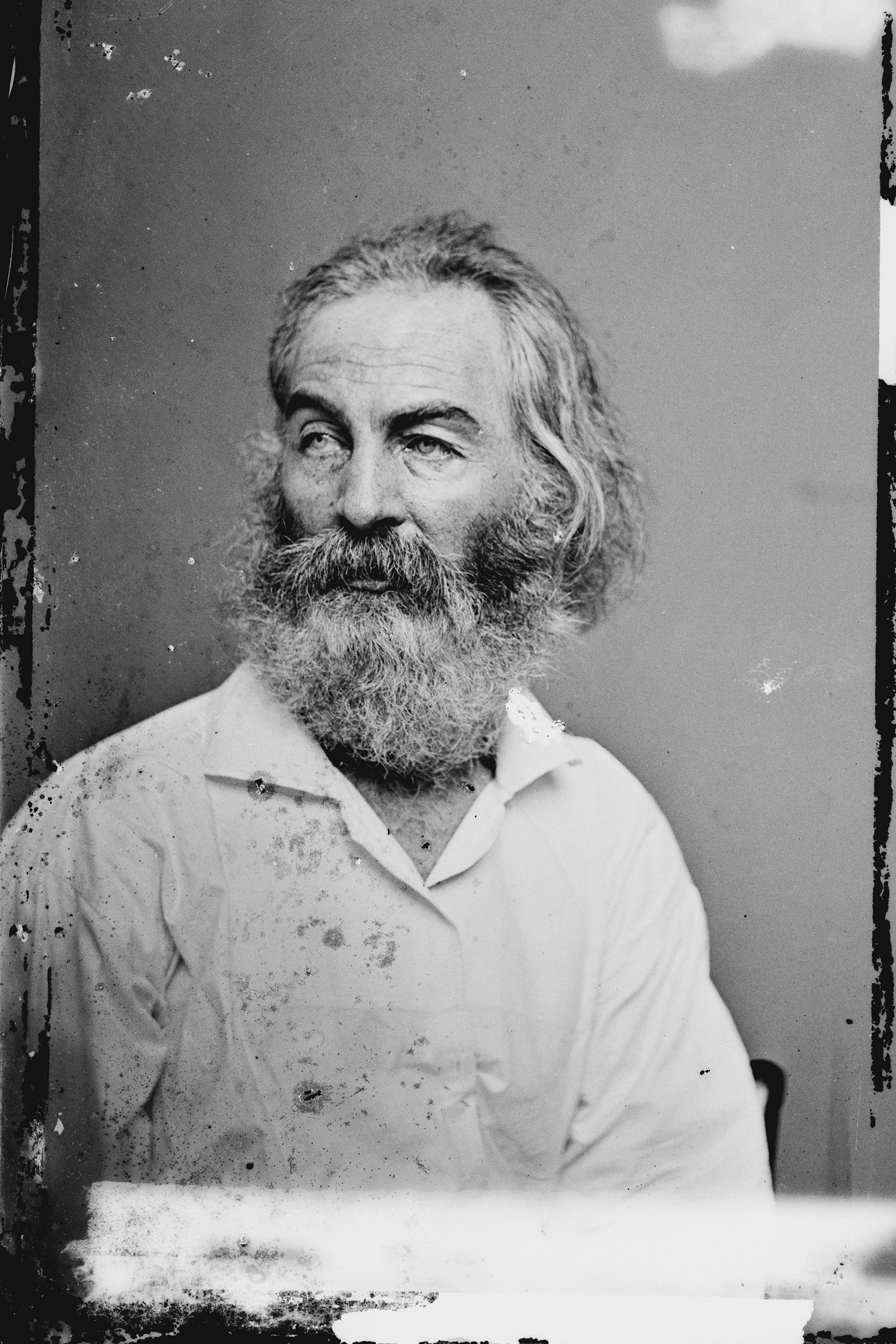

A. I confess: It’s been 50 years. A couple of things pushed me into a stronger engagement with the poet, starting three or four years ago. With Trump’s election, it came home to me that our democracy really was in trouble. This risky, promising, turbulent form of government and social connection actually could die out. Whitman insists that we must not allow this to happen without a fight.

Q. So Whitman was concerned that democracy could die?

A. He was. He felt that democracy faced two major dangers.

The first was hatred between Americans, which of course exploded about five years after Whitman published the first edition of “Leaves of Grass,” with the Civil War.

The second was fascination with what we could broadly call aristocracy. Whitman feared that Americans could come to hold each other in contempt, and that they could invest themselves in hierarchy, and begin worshipping those at the top. It’s easy to see that now, in 2021, these remain major issues.

Q. What did Whitman want to do about that?

A. Whitman believed that the democratic project was incomplete: We had the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. But we would never really succeed in going beyond feudalism until we had made democracy spiritual.

Q. What does that mean?

A. Whitman wanted the love of and appreciation for our fellow citizens to be at the center of our lives. He doesn’t usually try to debunk feudalism or solve person-to-person antagonism directly. He wants us to turn away from strife and the worship of charismatic figures and see how marvelous everyday people are – thus those vast catalogues, where Whitman depicts all sorts of people working and playing, and living their common lives. He helps us see those lives – many of them working-class, but far from all – as beautifully admirable, and so absorbing that it’s natural to turn away from the great and the special, celebrate your fellow countrymen and women and befriend them, even when there are strong differences.

Q. Did Whitman find it possible actually to do that?

A. Whitman came pretty close. During the Civil War he traveled to Washington and became what he called a hospital visitor. Almost every day, he went to the hospitals and moved among the sick and dying, offering a word of encouragement, something good to eat, a calm conversation. He did this for everyone and anyone: Union and Confederate.

He turned up on a ward once with two 10-gallon vats of ice cream, and served it out to men who had never tasted the wonderful concoction. He took dictation from men who could not read or write or who had lost the use of their hands, and helped them get letters, sometimes containing their last words, home to their families. If you stopped by one of the tents, you might see him playing 20 questions with a group of soldiers; or passing out writing paper, apples, and tobacco; or sitting on a cot holding a young man’s hand as he died, far from home, but not quite alone.

He was an everyday person, Walt, no big deal: a thriving member of the American democracy.