During the prime-time hour in the United States Monday night, President Donald Trump will begin talks with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, marking the first time that a sitting U.S. president has met with the dictator’s regime.

The historic summit, starting at 9 a.m. local time at the Capella Hotel in Singapore, comes after many months of negotiations and threats from both countries as the U.S. seeks to eliminate or limit North Korea’s nuclear capabilities. Politicians and citizens alike will watch closely to see how the two leaders react to each other and what, if any, deal will emerge.

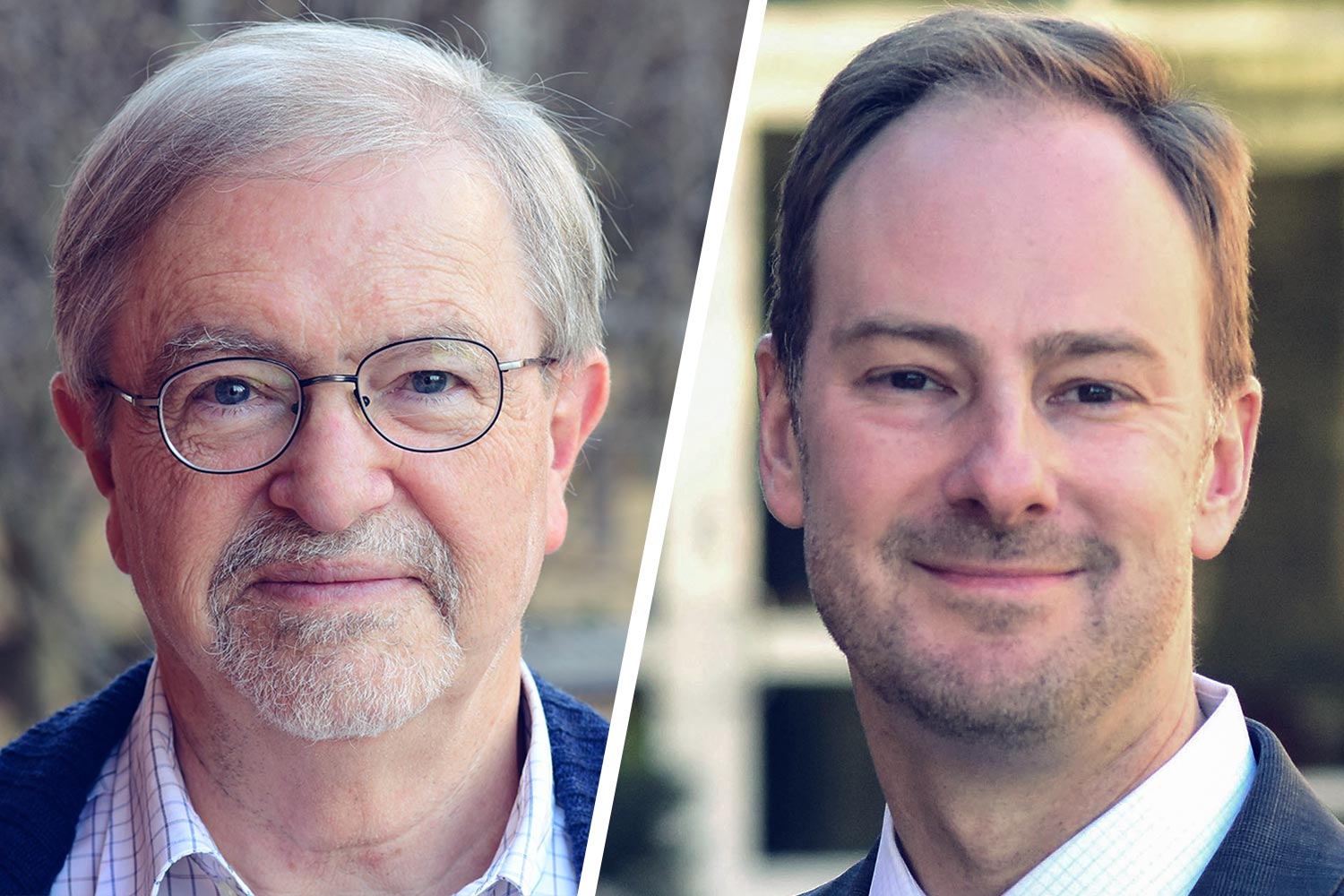

UVA Today sat down with two University of Virginia politics professors, Todd Sechser and Brantly Womack, ahead of Monday’s summit to discuss the key points they will be looking for in any new deal and the potential impact of the summit on U.S. foreign policy. Both also appeared on a Facebook Live session hosted by UVA’s Miller Center Thursday afternoon.

Sechser, an associate professor in UVA’s Woodrow Wilson Department of Politics and the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, is a nationally recognized expert on nuclear security. He is also a senior fellow at the Miller Center and co-author of the 2017 book, “Nuclear Weapons and Coercive Diplomacy.”

Womack, a professor of foreign affairs and the C.K. Yen Chair at the Miller Center, pioneered the study of asymmetric relations between large and small powers like the U.S. and North Korea. He has just returned from a short trip to China and has spent years studying that country’s impact on international relations.

Here are their thoughts, culled from our conversation and the Facebook Live discussion.

Q. What are the key things you will be looking for as news of the summit unfolds?

Womack: First, it’s important to note that this really is a historic meeting. It’s the first bilateral meeting between the United States and North Korean leaders, and the prospect of the meeting has already changed North Korea’s relationship not only with the U.S., but with other key players in the region like China, Japan and South Korea.

Sechser: I want to know what the North Koreans are going to ask for. They have been very quiet about it so far, offering vague promises instead of saying what they might want. That is the big question for me.

Related to that is how the president and key players in his administration, such as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Secretary of Defense Gen. James Mattis and National Security Advisor John Bolton, will react. They will play a big role in the success or failure of the summit.

Q. From the U.S. perspective, what is an optimistic outcome? Is full denuclearization truly on the table?

Sechser: At this point, the conditions under which North Korea would agree to full denuclearization are extremely narrow and might not even exist. They have spent billions of scarce dollars, subjected themselves to punishing international sanctions and become an international pariah to acquire nuclear weapons, and they likely have thermonuclear weapons at this point. It’s hard to imagine them exchanging that for a bit of economic aid and a handshake with the president.

At best, we can hope for continued negotiations after this summit that might set the stage for eventual reductions, or even a cap on North Korean’s nuclear weapons program. But verified nuclear disarmament, I think, is extremely unlikely.

Womack: I do believe the two sides could reach an agreement on some type of peace treaty to replace the current armistice and officially end the Korean War. That seems a bit empty and symbolic to us, but it is more meaningful to North Korea. I think it would be of considerable interest to both the U.S. and North Korea to reach that agreement bilaterally. Kim certainly does not want China involved in that type of agreement, and I don’t believe the U.S. does either. So that could be an important but formal gesture that could come out of this bilateral meeting.

Q. From an American perspective, what are some potential pitfalls the president might need to avoid when making a deal?

Sechser: Feeling pressure to come home with a deal – any deal – is dangerous. Though expectations have been lowered somewhat, they have been extremely, almost dangerously high and that has put enormous pressure on the president to come back with something to show for his efforts.

The question is what he might be willing to give up in exchange for that. I am hoping that the answer is not selling the farm, so to speak, in exchange for a few small concessions.

Related to that, it is a mistake to believe that North Korea has no leverage. They actually have a lot of leverage right now because it looks like the U.S. needs the deal more than they do. They are in this summit because they have nuclear weapons. If they did not have those, we would not be having this summit. That is what gives them leverage and they will be reluctant to give it up.

Q. What might North Korea hope to gain?

Sechser: Their big wish list would include the removal of American troops in South Korea, a peace treaty to the Korean War and some recognition of their right to have nuclear capability.

In one sense, however, the summit itself is a victory for them. North Korea has been wanting this summit for years, maybe decades. It makes them a legitimate nuclear power, if not a legally recognized nuclear power. It puts Kim on the same stage as the president of the United States. From a status and prestige standpoint, that is a victory for North Korea.

That’s not to say the summit is a terrible idea. It might be a sacrifice worth making, but it’s important to recognize that it is somewhat of a sacrifice for the U.S.

Q. North Korea appeared to dismantle a nuclear test site at Punggye-ri ahead of the summit. What do you make of that?

Sechser: They did blow up the Punggye-ri test site, but it was not clear the site was even viable any longer. Blowing it up is more of a symbolic gesture. Destroying it also means that the U.S. or other entities can no longer inspect the site to gather intelligence or data about what happened there.

I’m also not sure that North Korea needs to conduct further nuclear tests, at least for a while. They have already successfully tested what we think is a thermonuclear weapon, so from a technical standpoint they have succeeded.

Womack: They also made a conciliatory gesture in returning three U.S. prisoners before the summit, but as we know too well at UVA that is not the full story. [UVA student Otto Warmbier was imprisoned in North Korea for 15 months and died June 19, 2017 after he was returned to the United States in a coma with multiple injuries.]

Q. Absolutely. How might North Korea’s abysmal human rights track record factor into the talks?

Sechser: There has been resounding silence on human rights. I have not heard the president’s team mention it as part of the talks. Though you never know what might happen once the summit gets underway, I think it would be a surprise to North Korea if that comes up.

Q. Though this is a bilateral summit, leaders from Russia, China and even Syrian leader Bashar Assad have reached out to North Korea. What are the implications of those relationships?

Womack: Kim’s relationship with Chinese president Xi Jinping has grown closer, which is the opposite of the trend in North Korean-Chinese relationships recently. China’s cooperation in any nuclear inspections going forward will be important because they will be seen as the balancing element for North Korea in a multinational team of inspectors.

In fact, many would argue that Kim has already been successful because he has been able to solidify relationships with South Korea, China and even Russia. Those relationships have improved in part because of the impending summit, but they will have their own momentum if the summit fails. That could be a problem for the U.S., in part because of the president’s choice to withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal.

Q. How might that decision in Iran impact this summit?

Sechser: In some sense, it puts the U.S. between a rock and a hard place. If President Trump and Kim Jong Un agree to a deal, then Kim Jong Un can argue that any sanctions should be relaxed because he made the agreement. That gives China, especially, a pretext to relax sanctions and resist any U.S. pressure to reinstate them in the future.

On the other hand, if the summit collapses after Kim makes demands that Trump refuses, Kim can blame the U.S. for the failure and perhaps turn to Russia, China or other countries.

The unseen connection between walking away from the Iran deal and this summit is that it makes that story much more plausible. Kim can say the U.S. is to blame for not making a deal and point out that the U.S. has already walked away from an agreement that Iran had not violated.

Q. Anything else to add?

Womack: Though the stakes are high, the silver lining is that the situation in the region, which in March was looking very dire, has stabilized. Now, we are talking about an effective stalemate between North Korea not pushing its nuclear program further, at least not obviously, and the U.S. not immediately threatening a military strike. In the world we live in, that is some progress.

Media Contact

Article Information

June 8, 2018

/content/qa-uva-experts-share-what-they-will-watch-trump-kim-summit