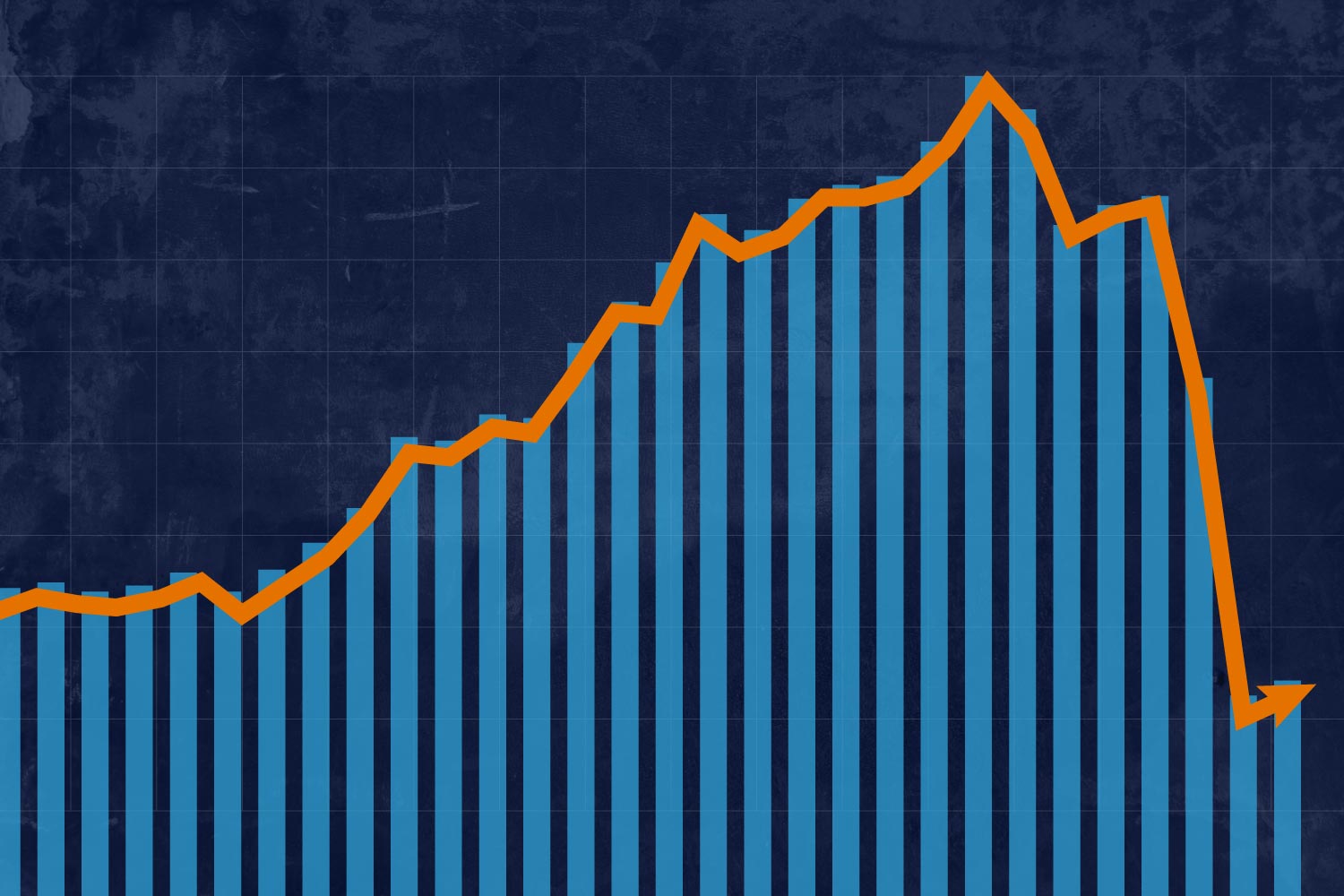

On Monday, the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged more than 1,100 points – its largest one-day points drop in history.

The rapid downturn, which came just over a week after the Dow hit a record high at the end of January, sparked a frenzy on the stock market floor and gave investors around the world cause for concern, especially when Asian and European markets also took a nosedive.

However, there were also positive signs. Though the points drop was large, the percentage drop, 4.6 percent, was far from the largest percentage fall on record – the 2008 financial crisis, for example, included larger percentage drops. By Tuesday morning, the market was already showing an uptick, though it remained volatile.

We turned to two professors in the University of Virginia’s McIntire School of Commerce to help make some sense of this roller coaster. David Chapman and Patrick Dennis both specialize in finance and have taught on subjects including investments, portfolio management and market volatility, among others.

Q. What could have caused Monday’s rapid drop?

Chapman: I think it is a bad idea to look for one simple cause, as tempting as that is. Financial markets are extraordinarily complicated and have millions of participants, across thousands of different platforms and with many different objectives. Some might be worried about the possibility of rising inflation, others might be worried about the impact of ongoing trade negotiations, still others are worrying about something else. All of those things matter, but there is not one simple cause.

David Chapman is a professor of finance in UVA’s McIntire School of Commerce and the area coordinator for finance. (Contributed photo)

Dennis: I agree. Psychology played a large role in Monday’s drop, perhaps more than anything else. People have been nervous for a while about the market being overvalued. It was almost like a game of musical chairs – you know the music has to stop soon and you don’t want to be the one caught out. I think that is what we saw Monday.

Overall, though, the economy is objectively doing well. Unemployment is low, companies are doing well, tax cuts are likely to kick in soon. Fundamentally, there is no one cause or bad number that stands out.

Q. There has been a lot of talk about inflation, especially after the January jobs report released Friday showed rising wages. Should Americans be concerned about inflation?

Dennis: Some economists and brokers are worried that wage growth could feed inflation and push the Federal Reserve to increase interest rates at a faster clip. However, this is not a new worry – we have known this for a while.

We also know that having higher wages will give workers more money to spend, which in turn increases company earnings. So, there are two countervailing forces at work that can hopefully balance each other.

Chapman: It’s not uncommon for a positive announcement like Friday’s jobs report to generate a short-term negative response. Our data shows that has happened many times before. Inflation could be part of that, but again, there are many other things that people are worried about. I think inflation itself is too simple an explanation.

Q. Can you put Monday’s drop in the context of other major downturns, such as those recorded during the 2008 financial crisis?

Chapman: In this case, it’s important to focus on the percentage drop, not the points drop. The top 20 points losses have all come in the last 20 years, because market levels are higher. Percentage-wise, the market dropped about 4 percent on Monday. Though it’s attention-getting, that does not even crack the top 20 in terms of worst percentage drops.

Dennis: It’s much, much less than what we saw on Black Monday in 1987 (a 22.6 percent drop) or during the financial crisis in 2008 (where the S&P fell by 39 percent during the year) In a way, I think Monday’s drop could be a good thing. Markets typically have some volatility, and that had been missing for a while.

Q. Should we be alarmed about another recession? If not, what would be a cause for alarm?

Dennis: I honestly don’t believe we need to be concerned about that right now. We are pretty much at full employment. Tax cuts will kick in both for companies and, on a smaller scale, for individuals. I don’t see anything on the horizon that would directly cause a recession absent some large geopolitical conflict.

Patrick Dennis is a professor of finance in UVA’s McIntire School of Commerce who has studied market volatility. (Contributed photo)

Chapman: I agree that there is not cause for immediate concern. I do think there is a good chance we could see a recession sometime in the next several years, based purely on history. Business moves in cycles and we have enjoyed a long expansion recently. It is reasonable to think a recession could come soon.

But picking the turning point of a recession is very hard to do. Even the greatest economists in the world do not date business cycles until after the fact. For now, I do not think there is any immediate danger.

Q. Is there anything investors can or should do to safeguard their investments?

Chapman: The first thing I would say is do not do anything immediately. It is virtually impossible to time the market and safely jump in and out based on a simple, observable thing like price change. The biggest bounces are almost always within a few days of the biggest drops, so I would recommend sitting tight for a few days.

That being said, I think it is reasonable to assume that the markets will be more volatile for the foreseeable future. Concerned investors should use this as an opportunity to reevaluate how much risk they are willing to bear and adjust their portfolio accordingly.

Dennis: One point to keep in mind is that the bond market is currently overvalued as well, so moving a lot of money from stocks to bonds is not as safe as it could be. Overall, I would not recommend any fundamental changes at this point, except perhaps to assess what you would do if a larger drop comes along. Are you willing to bear the risk of a 20 percent drop? A 30 percent drop? This is a good time to ask those questions.

Q. Do you have any specific advice for younger or middle-aged stockholders versus older stockholders?

Dennis: Younger stockholders should not worry right now. If you look back at major crashes, like the 1987 crash, the tech bubble or the housing crisis, Monday will just appear as a little speed bump. If you have 40 years to retirement or so, this is a nonissue.

Chapman: I agree; this does not change much for younger or middle-aged investors. Older investors, ideally, have already thought about how much equity they want in their portfolio. However, if you are closer to retirement and have not changed your portfolio in a while, it would be a good idea to take another look and make sure you are comfortable with the balance of stocks and bonds and the level of risk you are taking.

Media Contact

Article Information

February 6, 2018

/content/qa-whats-going-stock-market