“Hopefully, all the research we are putting into this is going to pay off and kind of show that this new technology is not just a fluke,” John Chrosniak, who graduated in December with a master’s in computer science, said. “This is something that is going to be seen as reliable for the general public.”

But vanquishing opponents at high speed is pretty cool, too.

The final race came down to the Cavalier Autonomous Racing vehicle, backed by a team of about 30 students, pitted against TUM Autonomous Motorsport, a German team. Because of its rough showings in previous years, the Cavalier team arrived at race week initially unseeded. But it breezed through a series of qualifying challenges, earning the top seed heading into the finals.

Unlike a traditional Indy race, where dozens of cars crowd the track and jockey for position, this kind of autonomous racing pits just one car against another, culminating a series of playoffs – or rather, race-offs. The most visual and exciting challenge is when the opponents take turns passing each other at increasingly higher speeds. The contest ends when one car reaches its limit or when its team throws in the towel.

And this year, UVA’s car was the fastest heading into that final test. It was the first time in two years the Wahoos had a shot at a championship.

In 2021, the UVA team burst onto the scene with the fastest American autonomous car on the track, but not quite as fast as an international team. A crash the following year dashed the team’s 2022 hopes. And last year, mechanical set-up problems and issues with high-speed stability dealt another setback.

“The past few years were definitely really hard,” Chrosniak said. “It was heartbreaking, just sitting there, observing the competition.”

But this year, the car was humming and, save for a few glitches, the machine was primed for a dogfight in the finals. On one fateful lap, it was the German car’s turn to be the “attacker,” to overtake the Cavalier machine as the speeds kept creeping up. But as the car from TUM pulled even, the Cavalier car on its own refused to back down, momentarily baffling the Wahoo team.

“I forget the exact numbers, but I think we were going like 80,” Chrosniak said, “and then all of a sudden it kicked into the next gear to about 120.”

It turns out the Cavalier car sensed that it was close to banging into the German car and performed a high-speed evasive maneuver, goosing the throttle to stay safe. So, a win for the technology, but a disqualification in the race and a runner-up trophy.

Even though it wasn’t a win, after two years of overwhelming setbacks, it sure felt like one, Behl said.

“I keep saying this, and I sound like a broken record, but it goes to show how remarkable the students are under pressure,” Behl said. “They are able to operate calmly, analyze the data, trust the rigorous engineering process and not get overwhelmed when something doesn’t work. They have the confidence to figure it out and do not hesitate to put in the effort. That’s the biggest lesson these students have learned.”

In the coming months, the Cavalier race car will undergo upgrades to its sensors and drive-by-wire system before the team races in June at a Formula One track in Monza, Italy. “We’re also planning another recruitment cycle this semester to welcome new students into the team,” Behl said.

Chrosniak is facing another and maybe more daunting challenge. His graduation means his time with the team is ending “and right now I am looking for jobs.”

“But I have to admit,” he said. “It’s really hard to find something that’s as exciting as this.”

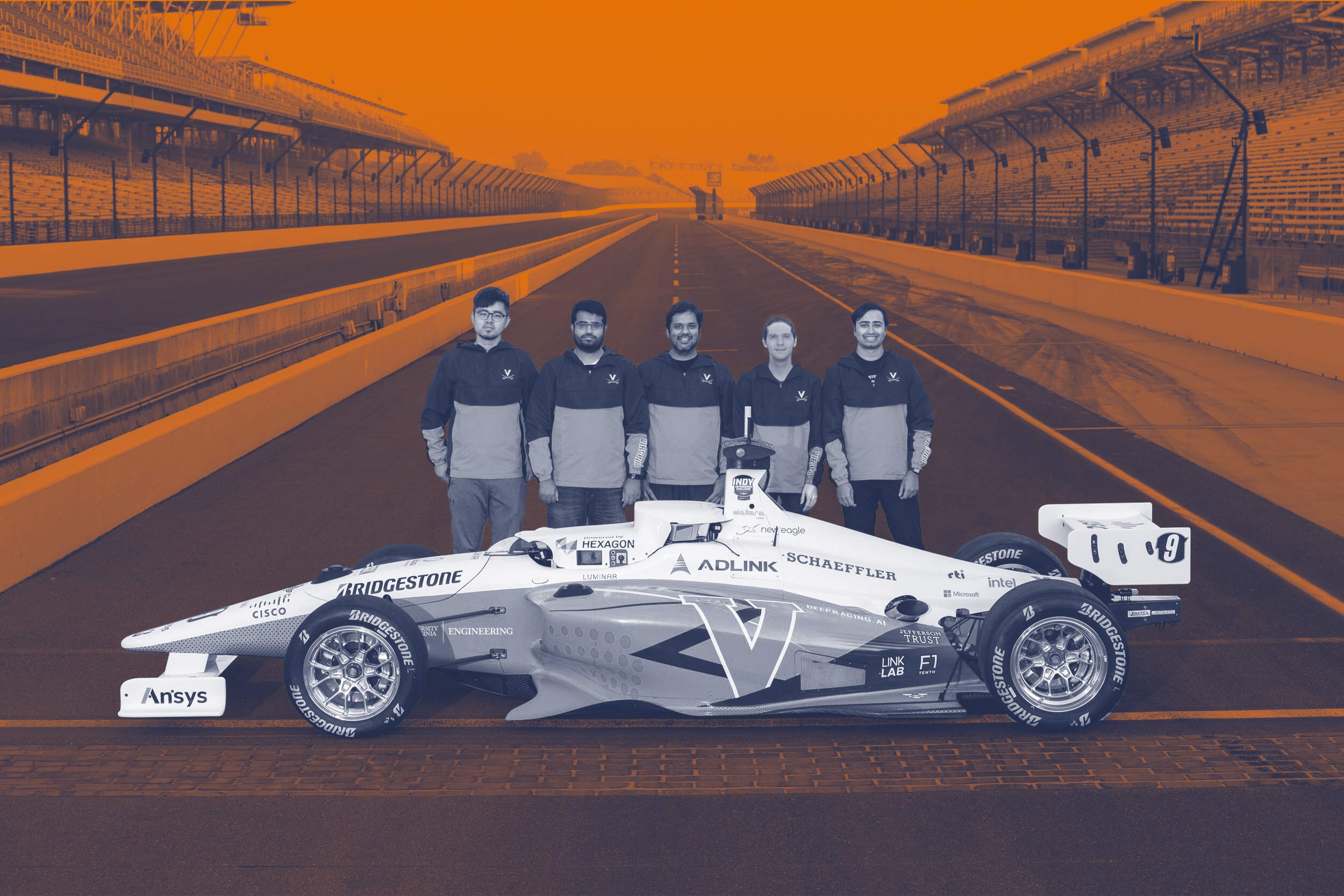

The Cavalier on-site race crew included Chrosniak, Aron Harder, Amar Kulkarni , Jingyun Ning, John Link, Shreepa Parthaje, Srikar Gouru, Siddharth Lakkoju, Michael Fatemi, Aditya Kak, Akash Pamal and visiting student Niklas Holle. The remote crew included Trent Weiss, Kyle McDonald, Ekow Daniels, Annabel Li, Mark Piatko, David Xiang, Harshal Nallapareddy, Preetham Minchu and Viraj Samant.