During one of the periods, she fell asleep in the 15-person class. Her professor asked why and Perkins responded, “I stayed up all night painting” for her studio art thesis.

Rather than being offended, professor Michal Sabat told her of a project he had going on with The Fralin Museum of Art. They were trying to figure out whether a donated 14th-century icon was authentic using X-ray fluorescence. There, she saw a chemist working directly with art.

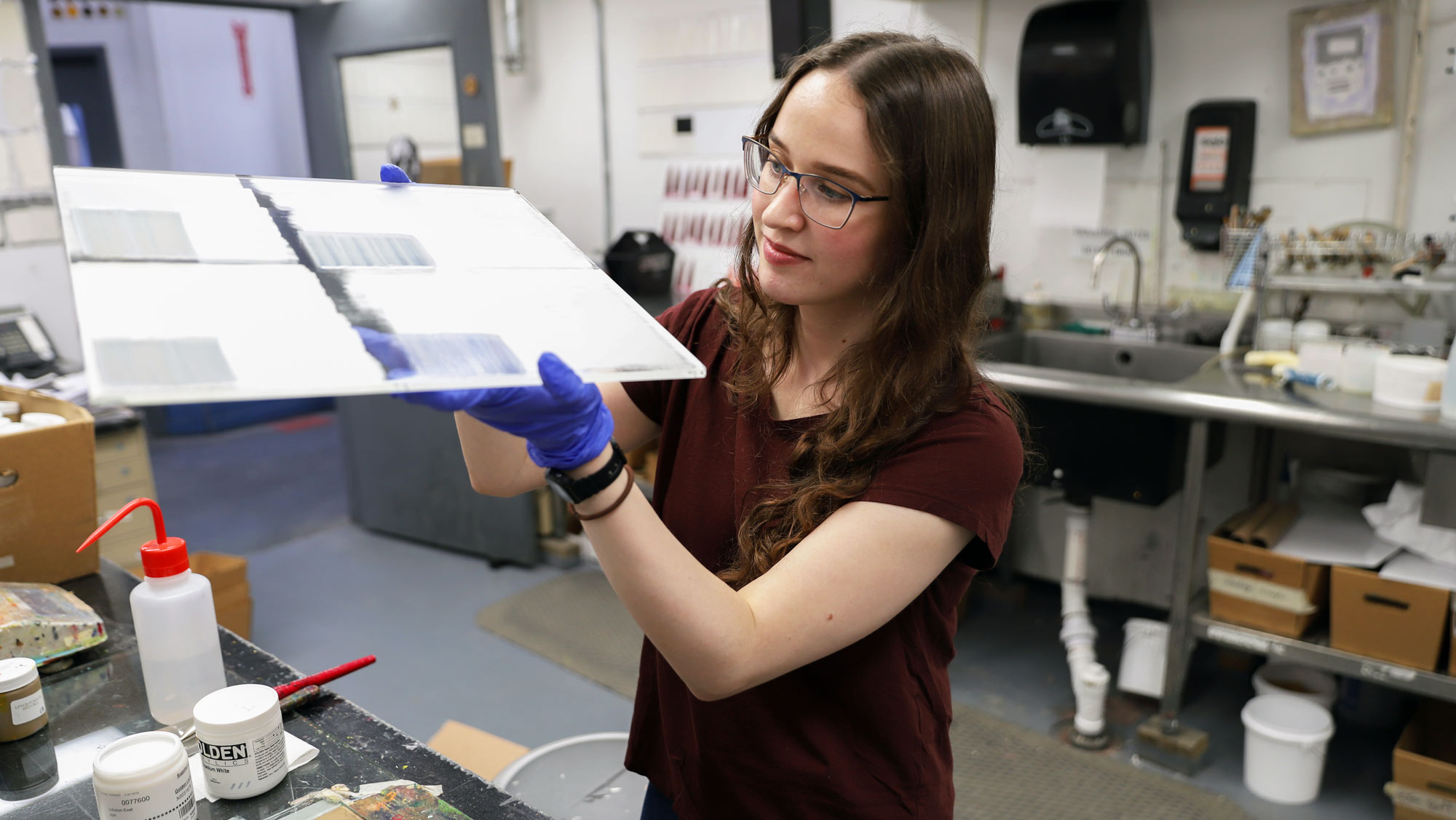

She had no idea at the time, but as a formulator for Golden Artist Colors, she, too, would be a chemist working in an artistic field. Or an artist working in a scientific field, whichever way you look at it.

Either way, she says having studied both chemistry and art helps a lot. “I know what to look for in a paint because I think about … how I would use it [as an artist],” she said.

And that’s precisely why the company CEO said Perkins is perfect for this job. “Not only are her skills adding value to artists, but she is also involved in providing resources for art conservators and collaborative research with art conservation scientists,” said Mark Golden, who also co-founded the company.

With the detailed eye of an artist, Perkins notices small differences in paint quality that are hard to catch. Correcting slight imbalances of an equation, like how much pigment to put in paint, is a quality of chemistry Perkins was attracted to as a student.

She thinks about being at UVA, where she first found out a job like hers was possible, and recalls a certain experience.

Her research professor, James Demas, showed her how to “bring creativity into science,” Perkins said.

As he showed her his work with fluorescent dyes and experimental design for the classroom, something clicked. “He showed me that chemistry doesn’t have to be clear and clinical. I was just like, ‘I think this is cool,’” she said.

“There’s chemistry with colors in it.”