August 7, 2008 — It's not a new energy-saving concept to turn down your thermostat at night, or leave your air conditioner off when no one is home. A University of Virginia research team plans to take that concept to the next level by using automated sensors and sophisticated software to enable heating and cooling systems to respond to the number of occupants in a room at any given time.

The volume of outside air that must be heated or cooled when 20 people are in a room is double that needed for 10, opening the possibility of significant energy savings from a climate control system that can respond to occupancy, Ron Williams, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, said.

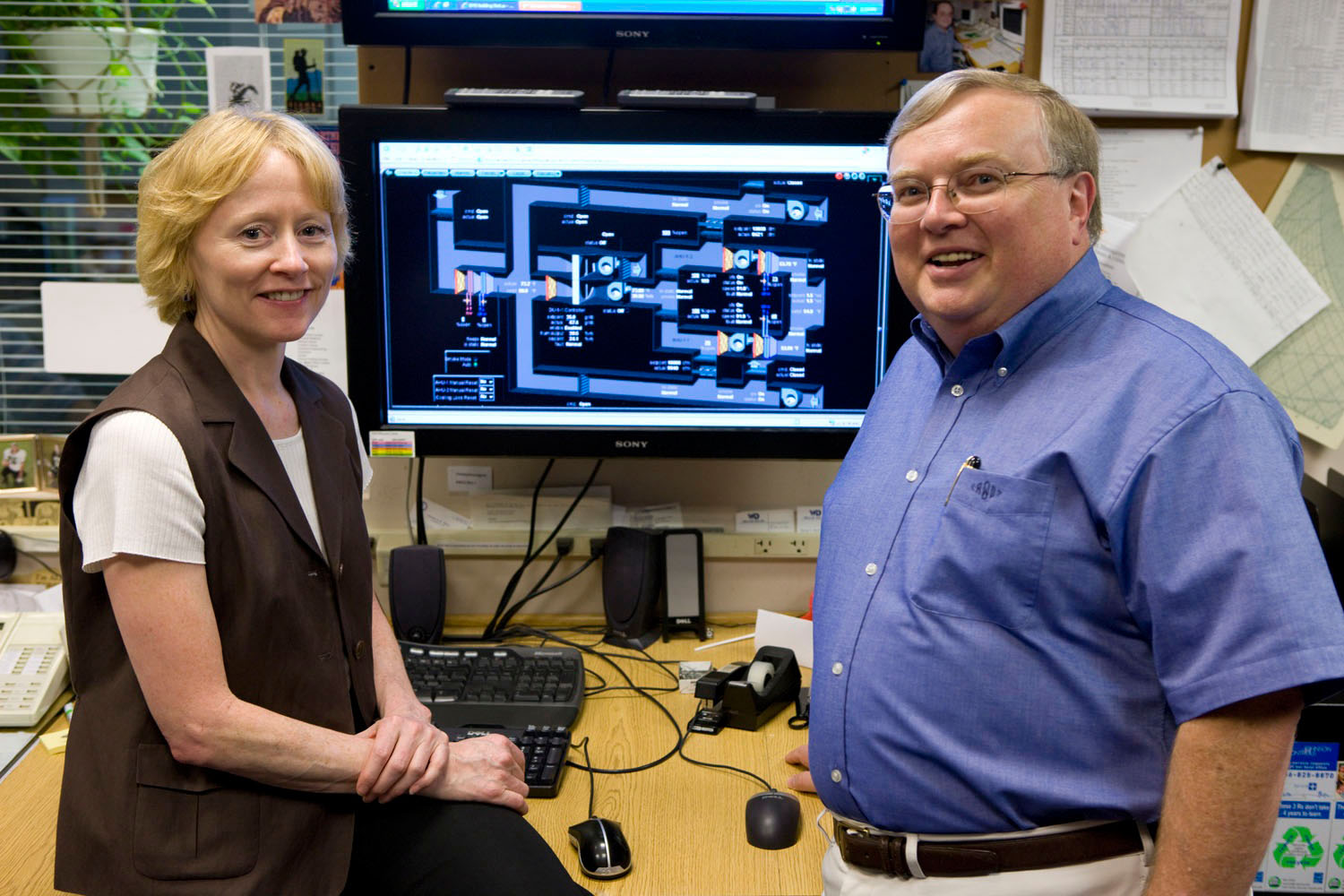

Williams and fellow researchers recently won a new U.Va. Collaborative Sustainable Energy Seed Grant worth about $30,000 to investigate how to make more intelligent climate control systems.

The most cost-effective measures to ensure adequate energy supplies and reduce greenhouse gas emissions come from energy conservation, rather than new energy technologies, Williams explained. Because the overall electric supply system is only about 33 percent efficient from fuel to end use, a one-unit reduction in consumption saves three units of new energy supply.

The idea of "intelligent building control" has been around since the 1970s, noted Williams, who wrote his dissertation on the subject in 1983. Only in recent years have computers and networking technology become so powerful and inexpensive that they could potentially be widely implemented in buildings at costs that could be justified in energy savings. Williams has estimated that occupant-sensing technology could produce as much as a 9 percent energy savings during the heating season, but said he would be happy with even 2 to 3 percent energy savings.

To help keep down the cost of such systems, the U.Va. research team will create a sophisticated — but simple-to-customize — computer model of a building space that accounts for how the occupants and outside temperatures impact heating and cooling needs.

The team will monitor one University space — a student activity room called "The Forum" in the Observatory Hill Dining Hall — seeking to better match the amount of heating and cooling of the space to the precise number of occupants, without diminishing their perceived comfort.

The schedule of reservations for the room will be used as a starting point for predicting occupancy, Williams said. The team will install sensors — probably video cameras with image recognition software — to detect the comings and goings of people. But the detecting poses several challenges, since people often come and go through the double doors in large groups and clumps, sometimes in both directions at once.

The team will correlate the occupancy data (predicted and actual) with measurements of air temperatures (inside and outside), air flows and electricity usage, to gradually improve their software model and controls.

"It's straightforward engineering," Williams said, "but — like the iPod — there are a lot of little problems that have to be overcome to make it all come together.

"I actually view this is as more of an embedded computing and information management problem, rather than an energy management problem."

Along with some University students, the research team includes fellow electrical and computer engineer Paxton Marshall and John Quale, an assistant professor of architecture and director of U.Va.'s ongoing ecoMOD project, which involves studies of the energy efficiency of modular housing prototypes.

The fourth team member is Cheryl Gomez, U.Va.'s director of utilities, who hopes that energy savings realized by this research can eventually be implemented more widely around Grounds.

About one-third of the University's 13.3 million square feet of space (in about 550 buildings) has been built or renovated since 1999, meaning the climate control systems are modern enough that they would benefit from intelligent building controls, she noted. In much of the rest, the heating and cooling systems are antiquated or in need of upgrades, and would be largely unresponsive to short-term thermostat changes.

This problem has not yet been addressed aggressively, Gomez said, because other "lower hanging fruit" offered more energy savings for lower costs, like installing fluorescent bulbs, LEDs and low-flow water fixtures across Grounds, among a number of measures that have won U.Va. 12 state and regional energy savings awards.

Reducing climate control costs may be one of the next targets for saving energy at U.Va., Gomez said. "What is neat about this proposal," Gomez said, "is that it marries the specialized thinking about how to better control our buildings and student research, and puts that in place here."

The volume of outside air that must be heated or cooled when 20 people are in a room is double that needed for 10, opening the possibility of significant energy savings from a climate control system that can respond to occupancy, Ron Williams, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, said.

Williams and fellow researchers recently won a new U.Va. Collaborative Sustainable Energy Seed Grant worth about $30,000 to investigate how to make more intelligent climate control systems.

|

The idea of "intelligent building control" has been around since the 1970s, noted Williams, who wrote his dissertation on the subject in 1983. Only in recent years have computers and networking technology become so powerful and inexpensive that they could potentially be widely implemented in buildings at costs that could be justified in energy savings. Williams has estimated that occupant-sensing technology could produce as much as a 9 percent energy savings during the heating season, but said he would be happy with even 2 to 3 percent energy savings.

To help keep down the cost of such systems, the U.Va. research team will create a sophisticated — but simple-to-customize — computer model of a building space that accounts for how the occupants and outside temperatures impact heating and cooling needs.

The team will monitor one University space — a student activity room called "The Forum" in the Observatory Hill Dining Hall — seeking to better match the amount of heating and cooling of the space to the precise number of occupants, without diminishing their perceived comfort.

The schedule of reservations for the room will be used as a starting point for predicting occupancy, Williams said. The team will install sensors — probably video cameras with image recognition software — to detect the comings and goings of people. But the detecting poses several challenges, since people often come and go through the double doors in large groups and clumps, sometimes in both directions at once.

The team will correlate the occupancy data (predicted and actual) with measurements of air temperatures (inside and outside), air flows and electricity usage, to gradually improve their software model and controls.

"It's straightforward engineering," Williams said, "but — like the iPod — there are a lot of little problems that have to be overcome to make it all come together.

"I actually view this is as more of an embedded computing and information management problem, rather than an energy management problem."

Along with some University students, the research team includes fellow electrical and computer engineer Paxton Marshall and John Quale, an assistant professor of architecture and director of U.Va.'s ongoing ecoMOD project, which involves studies of the energy efficiency of modular housing prototypes.

The fourth team member is Cheryl Gomez, U.Va.'s director of utilities, who hopes that energy savings realized by this research can eventually be implemented more widely around Grounds.

About one-third of the University's 13.3 million square feet of space (in about 550 buildings) has been built or renovated since 1999, meaning the climate control systems are modern enough that they would benefit from intelligent building controls, she noted. In much of the rest, the heating and cooling systems are antiquated or in need of upgrades, and would be largely unresponsive to short-term thermostat changes.

This problem has not yet been addressed aggressively, Gomez said, because other "lower hanging fruit" offered more energy savings for lower costs, like installing fluorescent bulbs, LEDs and low-flow water fixtures across Grounds, among a number of measures that have won U.Va. 12 state and regional energy savings awards.

Reducing climate control costs may be one of the next targets for saving energy at U.Va., Gomez said. "What is neat about this proposal," Gomez said, "is that it marries the specialized thinking about how to better control our buildings and student research, and puts that in place here."

—By Brevy Cannon

Media Contact

Article Information

August 7, 2008

/content/smart-climate-controls-would-heat-energy-conservation