University of Virginia Ph.D. student Murad Mumtaz is using the art of Indian miniature painting to highlight a disappearing aspect of regional history that holds many lessons for today’s religious and political relations.

The native of Lahore, Pakistan is one of a handful of artists worldwide still practicing the indigenous art form, which recalls a time of peaceful, open cultural sharing between Muslims and Hindus. The miniatures, each typically measuring only a few square inches, were often used to decorate ornate books.

Mumtaz learned the technique at the National College of the Arts in Pakistan, the first institution in the world to offer a bachelor’s degree in the subject. However, it was not until enrolling in UVA’s graduate art history program that Mumtaz fully immersed himself in the history of his craft and became determined to preserve its traditions.

Indian miniature painting flourished during the Mughal Empire from the 16th to the 18th centuries, well before the 1947 exodus of British colonialists divided the Indian subcontinent into Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan.

“Unfortunately, those two countries have become more and more associated with a religious divide – India with Hindu nationalism and Pakistan with Islamic extremism,” Mumtaz said. “In the pre-partition period, that was not necessarily the case.”

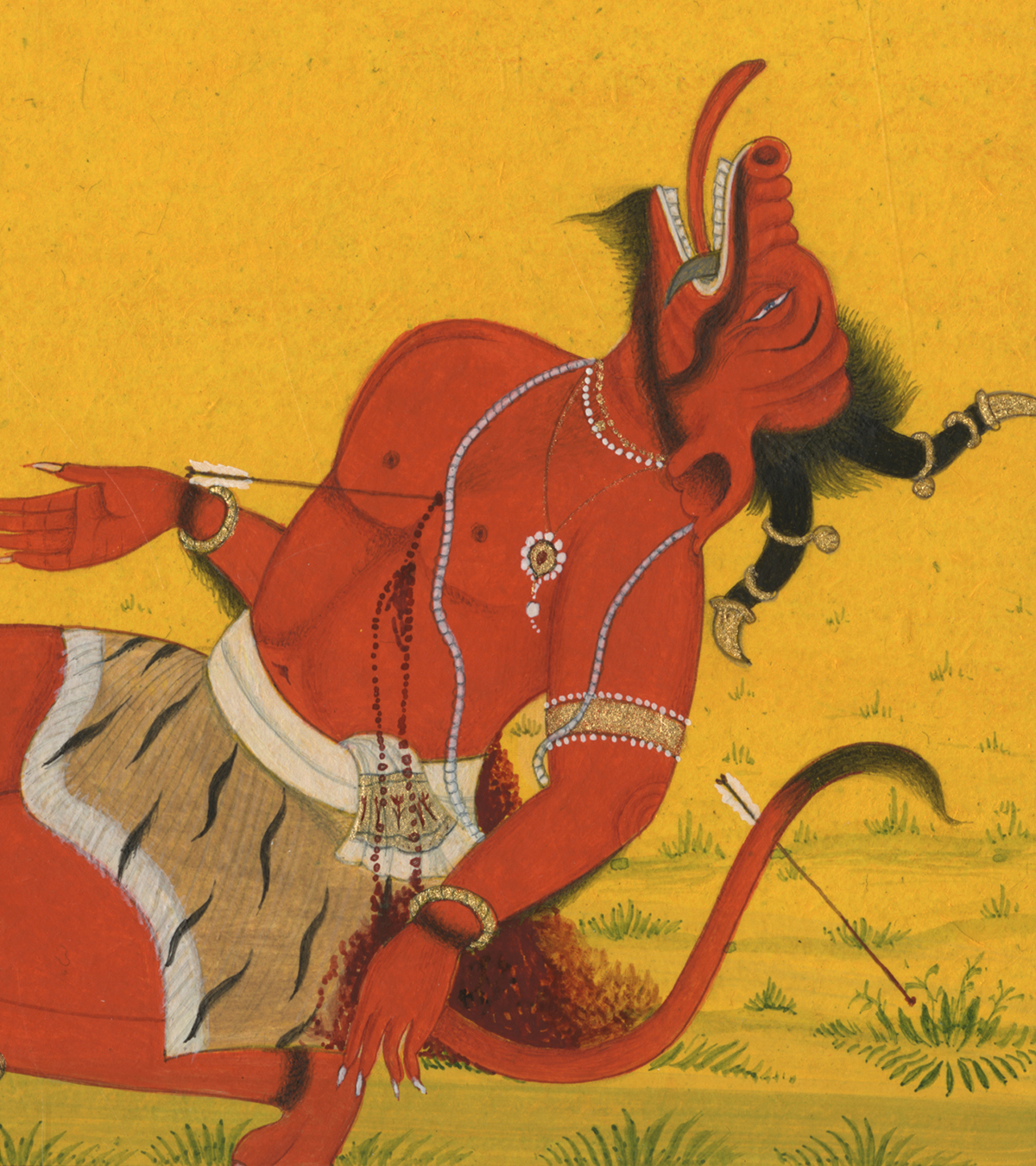

Mumtaz’s depiction of the Hindu god Brahma, the four-headed god of creation. The painting is inspired by North Indian painting from 18th-century Punjab, when depictions of Hindu mythological themes were very popular.

The Mughal emperors were Muslims presiding over a large Hindu population and their empire enjoyed periods of remarkable religious tolerance and collaboration between the two groups. That tolerant climate is reflected in the art that the Muslim-born Mumtaz studies and produces, which often focuses on Hindu mythologies and gods. Such subjects might seem alien to many Pakistani Muslims today, he said, but would have been familiar and enjoyable to their ancestors living in a more blended culture prior to the partition of India and Pakistan.

Highlighting a time of more peaceful religious interactions helps Mumtaz, the Pakistani grandchild of Indian immigrants, to understand his own blended heritage and make sense of fraught political and religious relations.

“I think it is a very good answer to the religious and political chaos of today’s world, at least for me personally,” he said. “Studying these paintings can be helpful for locating one’s identity in this post-partition era. It provides an anchor.”

Mumtaz makes many of his own paints using natural pigments and gold leaf, as used here in his depiction of a vanquished demon, referencing a story about Rama, an avatar of the God Vishnu who kills the demon that abducted his wife.

Today, he uses paper shipped directly from artisans in India who still practice 16th- and 17th-century paper-making techniques. He makes most of his pigments by hand, from minerals like lapis (blue), zinc (white), or orpiment (yellow), and also prepares his own gold paint from gold leaf. Paintings often take him two or three months to complete, using the delicate, repeated brushstrokes that are characteristic of the style.

“Murad has a very deep sense of the past that his family has participated in,” said Mumtaz’s faculty adviser, Daniel Ehnbom, an associate professor of art history. “His family was part of the cultural milieu that produced the material that he is now studying.”

“We must look back to history to understand who we are now.” - Murad Mumtaz

Mumtaz credits his father with inspiring his interest in preservation. The elder Mumtaz trained as an architect in England, starting with a focus on contemporary architecture. However, he soon became intrigued by the indigenous architectural traditions that had been lost in the colonial period. Today, his practice revolves around reviving traditional North Indian construction and building techniques and associated crafts.

“We must look back to history to understand who we are now,” Mumtaz said. “Continuing the tradition is perhaps the most important aspect of my practice.”

As one of the few artists still practicing traditional Indian miniature technique, Mumtaz feels a responsibility to keep the art from becoming only a relic in a museum and to share it with broader audiences. He has done an admirable job so far: his work has been shown in galleries in New York, Spain, Germany, India and Pakistan, as well as at major international art fairs like Art Dubai in the United Arab Emirates and Art Basel in Miami.

Media Contact

Article Information

October 27, 2015

/content/students-art-preserves-history-highlights-tolerance-south-asia-middle-east