In the homestretch of her time in office, President Teresa A. Sullivan isn’t spending much energy reliving the highs or lows of her seven-plus years on the Grounds of the University of Virginia. There are, after all, three months ahead, and plenty to do.

After opening a door in 2013 to explore UVA’s complicated legacy of slavery, Sullivan is again holding a mirror up to the University’s past with a new commission formed to take an unflinching look at UVA in the era of segregation. She’s also part of a statewide effort searching for solutions to the declines in population and jobs of rural Virginia.

And right around the corner: Final Exercises.

This will be Sullivan’s last graduation weekend as president. After nearly eight years in office, Sullivan will conclude her term on July 31. Following tradition, UVA’s outgoing president receives the honor of delivering the commencement address to students – some of whom Sullivan has known since they were first-years and, like her, may have succeeded despite difficulties along the way.

“I feel particularly proud to see that they’ve overcome those obstacles,” she said. “They’ve finished the course of study. Now they’re graduating and going off to a great new future. I love that time of the year.”

Sullivan, who describes Final Exercises as among her most enjoyable moments as president, addresses graduates and their families during the 2017 ceremonies. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications)

It’s an appropriate capstone to a presidency that made history from the start when Sullivan became UVA’s first woman president. Her tenure included an outsized share of national storylines, and – almost behind the scenes – pushed forward numerous initiatives that strengthened the institution for its third century.

“The University has only had eight presidents. Given the impact that women have had on the University’s progress, both in academics and culture, it was fitting that a strong woman would be chosen to lead the University at this juncture in history,” said George Keith Martin, rector emeritus. “And Terry was the perfect candidate to do so.”

Larry J. Sabato, founder and director of the UVA Center for Politics, a longtime professor and an observer of the University since arriving as an undergraduate student in 1970, said Sullivan has “achieved a great deal as president, and those accomplishments haven’t received the attention they deserve.”

“Part of it is that dramatic crises naturally grab the spotlight,” he said. “But it’s also that Terry subscribes to the philosophy that there’s no limit to what you can do if you don’t care who gets the credit.”

Major Accomplishments

When Sullivan arrived in 2010, she immediately recognized the need to address generational turnover among the faculty – or the “talent” as she likes to call them.

“We had one entire department over in Engineering that was past retirement age,” she recalled as an example. “And we didn’t have any plans for replacing them.”

“It’s good to be able to step back and say, ‘That’s going to be great for the University.’”

- Teresa A. Sullivan

President

Complicating matters, the national economy was in recession. Further, UVA was falling far behind peer institutions in faculty pay. In response, Sullivan won Board of Visitors support for a multiyear plan to boost salaries, improve packages to attract top researchers, recruit the best professors on the market, and convince young faculty stars to stay here.

“That’s hugely satisfying to me,” she said. “It’s good to be able to step back and say, ‘That’s going to be great for the University.’”

Other significant achievements during Sullivan’s time in office include:

- Implementation of the Cornerstone Plan, a five-year strategic plan positioning UVA for success in its third century;

- Completion of a $3 billion capital campaign, and a 40 percent increase of philanthropic cash flow between 2010 and 2017;

- Establishment of a Strategic Investment Fund that provides significant support for scholarships, research, academic initiatives and health care services without using tuition dollars;

- Restoration of Jefferson’s Rotunda, and the launch of UVA’s bicentennial commemoration;

- Expansion of the University’s global aspirations, including the opening of a UVA office in China;

- A renewed emphasis on affordability and access, with targeted action to limit student debt and enhance financial aid and scholarships for Virginians; and

- Numerous capital projects, including new residence halls on Alderman Road, renovations to New Cabell Hall and dedication of the School of Engineering and Applied Science’s Rice Hall.

She also has led the recruitment of a new generation of University leadership, including almost all cabinet-level vice presidents and eight new deans. The UVA Health System was reorganized with new leadership as well, including the creation of the position of executive vice president for health services. Sullivan helped reinvigorate research and patient care missions, Martin added. And UVA’s Medical Center now stands ranked No. 1 in Virginia, pursuing a straightforward goal to be the safest hospital in America.

During Sullivan’s tenure, UVA also transformed how it manages its $3.4 billion budget. An emphasis on operational efficiencies identified millions in annual savings, and for the first time, the University devised a long-range financial plan and began planning budgets on a multiyear basis, rather than starting over each year.

A major restoration provided needed repairs and improvements to the Rotunda – including new marble capitals, additional classroom space, a fully restored Dome Room and safety and accessibility enhancements. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications)

“Those changes aren’t glamorous. They don’t make headlines,” she said. “But if you don’t do them, nothing else works well.”

UVA also has responded to student interest in more robust advising and career services programs – an area that emerged during development of the Cornerstone Plan as a key to improving the UVA experience.

The result: a comprehensive restructuring of the process, now known as “Total Advising.” The new approach expands advising from a traditional, narrow conversation about academics to one addressing multiple questions students confront. Total Advising includes academic advising, career counseling and personal coaching, and connects students with alumni mentors and internships. The changes, Sullivan said, put UVA’s high-caliber students in an even stronger position to succeed after they leave Grounds.

“These are incredible students. It’s not just that they are smart,” she said. “They strike me as mature beyond their years. And I think employers also sense this.”

Confronting History, Growing Diversity

In June 2017, the Board of Visitors unanimously approved the design of a Memorial to Enslaved Laborers. Featuring a circular, stone wall etched with the names of slaves who built and sustained the early University, the memorial will be installed on a grassy area near the Rotunda and Brooks Hall.

It will provide a tangible, public-facing symbol for the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University, whose work in researching and teaching about the legacy of slavery here has changed the conversation about a long-neglected facet of UVA’s illustrious-but-complex history. Sullivan is determined to tell the whole story about the University’s history, Martin said.

As the commission conducted its work, the institution itself was making meaningful progress in diversifying and growing enrollment, and in enriching the socioeconomic composition of the undergraduate population.

The Memorial to Enslaved Laborers will formally acknowledge the work and the lives of enslaved African-Americans who built and sustained the University. (Image courtesy Howeler + Yoon)

Institutional data show that UVA has grown more diverse and open during Sullivan’s time as president while enrolling more Virginia residents than at any time in its 200-year history. In Sullivan’s inaugural academic semester – fall 2010 – the University’s undergraduate enrollment stood at 14,445 students, including 10,076 Virginians. That year, 27 percent of undergraduates were minorities and 8.7 percent chose “African-American” as at least one of the racial categories with which they identified.

In the fall of 2017, undergraduate enrollment had climbed to 16,034 students, including 11,118 Virginians. Of those, 31.6 percent were minorities and 8.4 percent chose African-American as at least one of the racial categories with which they identified. Due to rising enrollment overall, the percentage of African-American students remained steady, but the number of African-American undergraduates increased from 1,251 in 2010 to 1,342 in 2017.

In Sullivan’s first year in office, 31.4 percent of undergraduate students had demonstrated financial need, a figure that increased even as the size of the student population increased, to 32.4 percent in the current academic year.

Last fall, 452 first-year students were the first in their families to attend college, up from 318 in 2012, the year UVA began collecting data on first-generation enrollment.

“It’s not an accident. We do work at it,” Sullivan said “We’ve made a real effort in the past couple of years to remind the people of Virginia that we have very generous financial aid here. We’ve made a real effort to think substantively about first-generation students and what will help them make better adjustments to college.”

Martin, who was one of a small number of African-American students during his time as an undergraduate at the University in the early 1970s, lauded the progress the University has made under Sullivan. “I am truly impressed with Terry’s commitment to enhancing the student experience at the University,” he said. “She understands that all students benefit from learning and working in a diverse and inclusive environment. She has been steadfast in her commitment to diversity and inclusion, and we are seeing the fruits of her labor in this critical area.”

Loving Virginia

Much like those first-generation students, Sullivan had to make her own adjustments as she assumed her role at UVA and stepped into a challenging job at a place that reveres its history and traditions.

Sullivan knew the learning curve at UVA would be steep. Not only had she not served as a university president, she hadn’t worked or lived in Virginia. She grew up in Arkansas and Mississippi and served in academic and administrative leadership posts at the University of Michigan and the University of Texas before coming to Charlottesville.

Sullivan needed to get up to speed on Virginia culture and politics, on the particular characteristics of UVA alumni, and on traditions here.

“I’ve tried to be very respectful of the traditions that are important and central to the University,” she said.

She also fought against what she considered to be “pseudo-traditions.” Example? The annual Wertland Block Party, a private street party held just before fall classes begin and marked by excessive alcohol consumption.

“Not a tradition,” Sullivan said flatly. Last summer, she called on the student community to put an end to the event, though the University has no direct control over it.

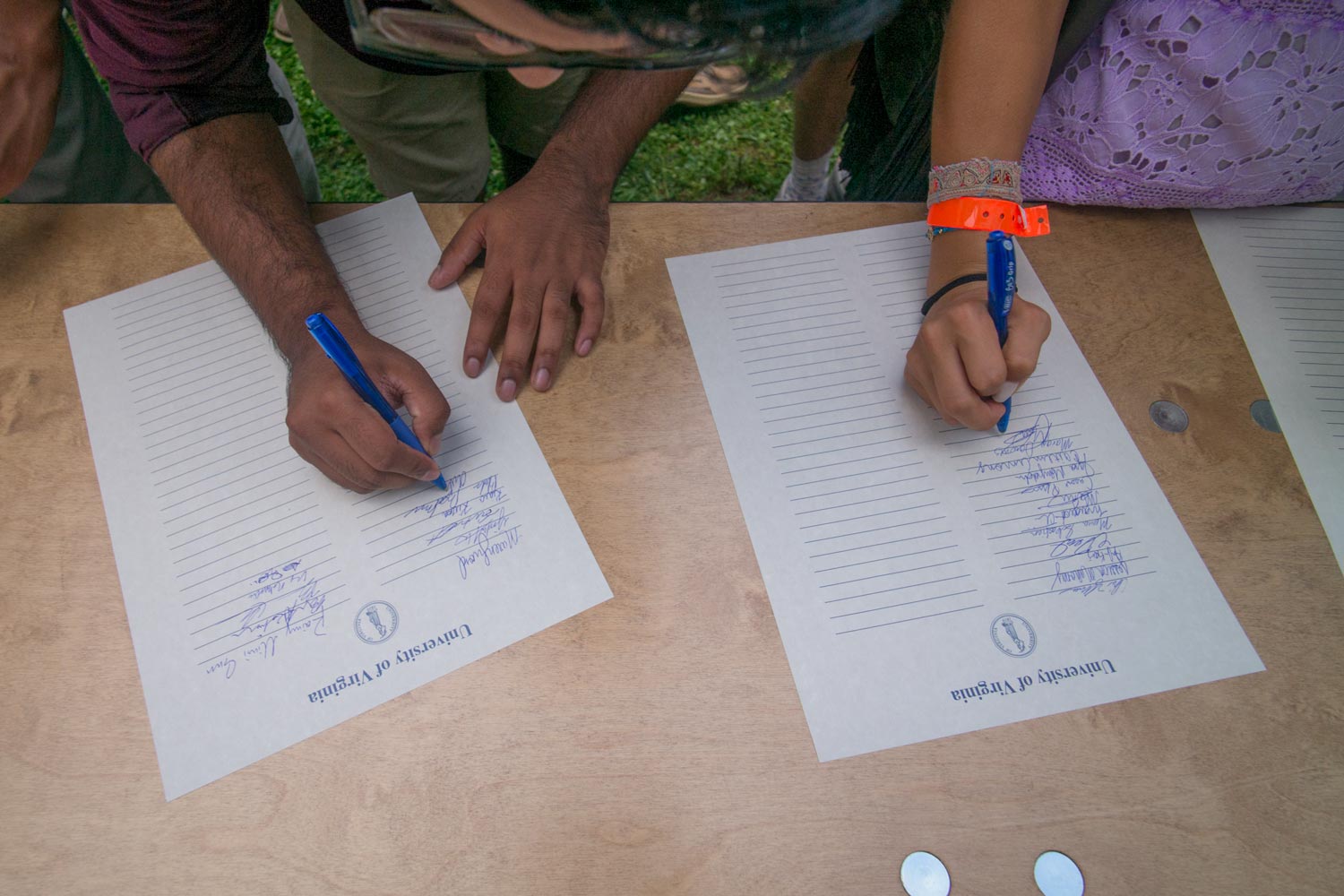

Other UVA traditions ring true and treasured for good reason, and Sullivan embraced them. Student self-governance, for example. And Opening Convocation, when first-year students gather in front of the Rotunda at the start of their collegiate careers and sign UVA’s simple but distinctive Honor Pledge.

“Students take a great deal more responsibility here than at any other institution with which I am familiar,” Sullivan said. “What’s different about Virginia is that we believe our students are adults. They come here at 18. They’re old enough to serve in the military. They’re old enough to be on a jury. They’re old enough to vote. They are adults, and we treat them like adults. And, frankly, most universities do not.”

At an institution rich in history, Sullivan embraced traditions such as Opening Convocation, when first-year students sign UVA’s Honor Pledge. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications)

Sullivan has enjoyed beginning her own traditions, as well. During her first year in office, she arranged a reception at Carr’s Hill – now an annual event – at which faculty authors display books published during the year and visit with one another about their works.

“These are not faculty who are resting on their laurels,” she said. “Producing a book is a big deal in the life of an academic in many fields.”

Sullivan also loved surprising students who were about to receive extraordinary honors, such as national scholarships or other major academic recognition. Without any hint, she sometimes would bring an unsuspecting (but nervous) student into her Madison Hall office to break the news.

“Just watching them dissolve in joy has been fun,” she said.

Reflective of her personality, those kinds of moments – intimate and relatively quiet celebrations of academic accomplishment – resonate with Sullivan. They offer personal rewards in a job that demands attention and energy around the clock.

Nancy Rivers, who served as chief of staff for nearly all of Sullivan’s presidency, said Sullivan stayed true to a commitment to connect directly with students, faculty, staff, alumni, parents and others in UVA’s orbit as often as possible. The informal celebrations with students in Madison Hall were among many examples that occurred outside of the public eye.

Rivers (now an administrator in the Department of Athletics) and her colleagues regularly marveled at the endless hours Sullivan devoted to her role.

“Herculean stamina,” she said of her former boss. “She personifies the idea of the ‘servant-leader,’ one who leads with determination and vigor, but always cognizant of the human impact of her decisions on people and initiatives.”

While appreciative, Sullivan shrugs off those kinds of plaudits. “Every president works hard,” she said simply.

Even so, Sullivan knew coming in, and would be reminded time and again, that serving as a public university president these days is no simple task.

A Job Like No Other

In a 2017 white paper on the modern university presidency, consulting firm Deloitte noted the growing complexity of the job, declaring that “the role of college president has no analog in the modern business world.”

“It is accountable to a dizzying array of stakeholders and constituents, on campus (students, faculty, and administrative staff) and off; parents who are hyperinvolved in every aspect of their child’s experience; community leaders seeking to influence the university’s role in town; alumni who want to maintain the experience they had as students; and, in the case of public institutions, political leaders who demand greater accountability even in the face of dwindling state support,” Deloitte’s report summarized.

“The job requires administrative and financial acumen, fundraising ability, and political deftness. Presidents must be accessible and responsive but also measured and restrained in an era driven by 24/7 news coverage and the inflammatory nature of social media. They often need to balance the pressures of society to improve the ‘return on investment’ of education at their institution as well as manage the pressure from community and political leaders around critical issues such as sexual assault and legalized guns on campus.”

In short, serving as the top administrator at a public institution can be – in addition to a financially and professionally rewarding occupation – a tangle of politics, personalities, competing priorities and, in the case of a university like UVA, a microscope through which thousands of deeply invested and loyal alumni study every move.

Sullivan was inaugurated as UVA’s first woman president in April 2011. Her husband, law professor Douglas Laycock, center, joined her as then-Rector John O. Wynne administered the oath. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

It is, of course, bigger than all of that. Deloitte’s report speaks to the administrative and fiscal challenges of higher education leadership. That bigger meaning – the part about educating citizen leaders and inventing things and lifting people up through education and curing sickness – is what drew Sullivan to UVA.

“I also had another, deeper resolve,” she added. “Public higher education in the United States is at a crossroads. As successful as we have been, we’re still under attack from both the right and left. There are a few great public universities that simply must survive as great public universities – or the whole enterprise is doomed. To me, that public mission – and maintaining it at a very high level of quality – is important.”

The criticisms of higher education have continued unabated, though. From the left, critics suggest public universities function too much like private corporations. From the right, a broad brush paints them as an “ideological monoculture” that fears technology’s disruptive potential on education delivery.

“I found myself over and over again making the case that these broad-brush critiques are not true of higher education generally, but for sure are not true of Virginia,” she said.

Facing the complexities of overseeing an operation the size of a Fortune 1000 company, but with the social and political pressures that come with its public status, Sullivan boiled down her approach to the resulting unpredictability: “Either give up and go home – which is not congenial to me – or keep pushing ahead.”

No, giving up is one thing that Sullivan has refused to do in the face of some of higher education’s most famous – and infamous – crises.

A String of Challenges

Joining a long line of national media, Fortune magazine in early 2015 took a shot at deconstructing the series of national-level crises that descended on the University of Virginia in the last half decade, and the cumulative effect those events surely must have had on UVA’s leader.

“The Unluckiest President in America,” concluded the Fortune headline.

At the time, the University community was emerging from a period of searing publicity and introspection following the infamous Rolling Stone article that told the story of a gang rape at a UVA fraternity house – one that ultimately turned out to be untrue.

The experience ended up being a cautionary tale about rushing to judgment and media ethics, and about accountability. Then-Rector Martin described the magazine piece as “drive-by journalism” during one public meeting.

“We recognized there were some real issues that we could deal with, and deserved to be dealt with, and tried to have something good come out of the crisis.”

- Teresa A. Sullivan

President

But aside from being synonymous for bad journalism, “Rolling Stone” also came to represent a time when the University took the hardest look in its history at issues around student safety and sexual harassment and assault. In the wake of the debunked article and a federal review of UVA’s Title IX practices and structure, the University revamped how it handles cases of alleged sexual assault and misconduct.

“We recognized there were some real issues that we could deal with, and deserved to be dealt with, and tried to have something good come out of the crisis,” Sullivan said. “I think we had some success with that.”

To even have a magazine choose an adjective such as “unluckiest,” however, requires more than one crisis. And Sullivan has endured more than a fair share, from her own forced resignation and reinstatement in 2012 – following widespread public demonstrations of support – to the disappearance and murder of student Hannah Graham in 2014, and the ultimate conclusion by police that Graham’s death and that of Morgan Harrington five years earlier were at the hands of the same killer, Charlottesville resident Jesse Matthew.

Later, in August 2017, Charlottesville found itself in America’s cultural crosshairs when white supremacists marched across the Academical Village carrying torches, and racist demonstrators clashed the next day with counter-protestors near the city’s Downtown Mall.

On Grounds, Sullivan formed a working group of deans and other community leaders to assess the University’s response to the events and bring recommendations for next steps that would enable UVA to recover and heal from the tragedy and move forward with new policies and actions.

Students, faculty, staff and community members massed on the Lawn for a candlelight vigil rejecting hatred in August. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications)

“The events of August were heartbreaking and infuriating,” she said. “The positive result is that those events compelled us to study our policies and to make changes that will put UVA in a stronger position in the future.”

Sullivan would never argue against the idea that being president is difficult. It comes with the territory. But the unluckiest? In America? Even with all that has happened between the Fortune article and today, Sullivan would have none of it. She referenced the challenges other college presidents have confronted, including the mass shooting her colleague and friend Charles Steger experienced in 2006 while president of Virginia Tech. She shook her head at the idea of being higher education’s unluckiest.

“I reject the term entirely,” Sullivan said.

Through all the crises, she pointed out, the University community learned that it possesses a deep, enduring resilience.

“The students, in particular, always responded well,” she said. “They showed a great ability to not inappropriately generalize from something bad that had happened to the entire institution. They were able to view it in a mature way to say, ‘This thing was bad, but all these other things were actually good.’ I always appreciated the ability of our students to do that.”

“Terry impressed me with her ability to focus on a crisis with laser intensity while at the same time she was able to deal with the mundane aspects of her job without missing a beat,” Martin said. “She brought the same intensity and focus to the day-to-day operations as the crises. And although she dealt with numerous crises during her tenure, she was never deterred from her commitment to the mission of the University.”

Rewarding Times

Like so many others, Sullivan reveled this year in the rise of the men’s basketball team and the success of the women’s team. Starting the season unranked, the men tore through the regular season and Atlantic Coast Conference schedules in record fashion, finishing 31-3 and securing the overall No. 1 seed in the NCAA Tournament before a heartbreaking first-round loss. The women’s team earned its first tournament bid since 2010 and, with Sullivan in attendance, won its first-round game against California.

Celebrating those successes and others provided Sullivan plenty of memorable moments as president. In 2011, she was on the field when the men’s lacrosse team accepted its national championship trophy. In 2014, she was on the Greensboro Coliseum floor when Akil Mitchell, a 6-foot-8 power forward who also happened to be an intern in the President’s Office, handed Sullivan the ACC basketball championship trophy.

“It was so heavy I started to sink under it,” she laughed. “He had to help me hold it up.”

In 2015, she was on the field in Omaha, Nebraska, after the baseball team won its first national title. Last summer, she celebrated swimmer Leah Smith’s 2016 Summer Olympics gold and bronze medals as Smith was honored on National Girls and Women in Sports Day.

Sullivan reveled in attending athletic competitions, student performances and participating in community events during her time in office. (Photo by Jack Looney)

In addition to attending countless other athletic events, Sullivan also enjoyed attending student musical and theatrical performances, hearing the Cavalier Marching Band practice in the field below Carr’s Hill, and representing UVA in community events such as the annual Martin Luther King Jr. celebrations and many others.

Through a window in her Madison Hall office, Sullivan has a clear view of the Rotunda across University Avenue. To the right, she can see the Pratt ginkgo, which delighted her anew each fall when its leaves raced from green to brilliant gold before carpeting the ground around the trunk almost all at once.

“I’m so happy with how the Rotunda renovation turned out. I just like being there,” Sullivan said, echoing a sentiment probably shared by the seven presidents who preceded her. “Every view is terrific.”

Sullivan and her husband, UVA law professor Douglas Laycock, plan to sojourn in Texas on a research leave after her presidency concludes this summer. Laycock is scheduled to visit at the University of Texas School of Law beginning in 2019. Sullivan plans to conduct research to prepare for a return to UVA for her classroom passion, teaching demography. Her successor, James E. Ryan, begins his time as UVA’s ninth president on Aug. 1.

“Being president for me at UVA was a capstone. It was not a steppingstone,” Sullivan said. “I love universities. This is a great university, and it’s been a terrific experience to be associated with it.”

Media Contact

Article Information

April 24, 2018

/content/sullivan-years