The story of the University of Virginia is told by its people, from its famous founder through the thousands of alumni scattered around the globe today. It’s also told through the objects that they leave behind – tangible evidence of the extraordinary men and women who have shaped UVA over its two-century history.

In honor of the University’s approaching bicentennial, UVA’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library has launched “The University of Virginia in 100 Objects,” an exhibition showcasing some of the most important, quirky and powerful objects in UVA’s history. Opened Thursday, the exhibit will run through June 22. It is based on a companion book, “Mr. Jefferson’s Telescope: A History of the University of Virginia in One Hundred Objects,” by Encyclopedia Virginia editor Brendan Wolfe, available through the UVA Press. Encyclopedia Virginia is a project of the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, which works in partnership with UVA.

The objects range from artifacts of UVA’s founding – including a telescope and walking stick that founder Thomas Jefferson used – to modern-day mementos. Some are light-hearted, like a menu from a popular tearoom that stood near Barracks Road and a special-edition Barbie doll clad in UVA gear. Others are powerfully serious, like a photograph of an enslaved laborer on Grounds or the lawsuit papers that forced the University to finally admit women in 1970.

“This is the most ambitious exhibition we have ever done,” Special Collections curator Molly Schwartzburg said.

The displays include items loaned from private individuals and other institutions that have never been viewed at UVA before. Although most of the objects are in the Harrison and Small galleries in the Special Collections library, others are scattered across Grounds at 16 satellite locations.

The exhibition does not shrink from controversy, Schwartzburg said.

“It tells very powerful stories, some of which will leave visitors with mixed feelings about specific moments in the University’s history,” she said. “It also raises important questions about the selective process of writing history – what is brought to the forefront and what is left out. One hundred items cannot even begin to cover the history of this university, but it’s a compelling start, and a great way to kick off the bicentennial.”

Below, take a look at 10 of the objects featured in the new exhibition.

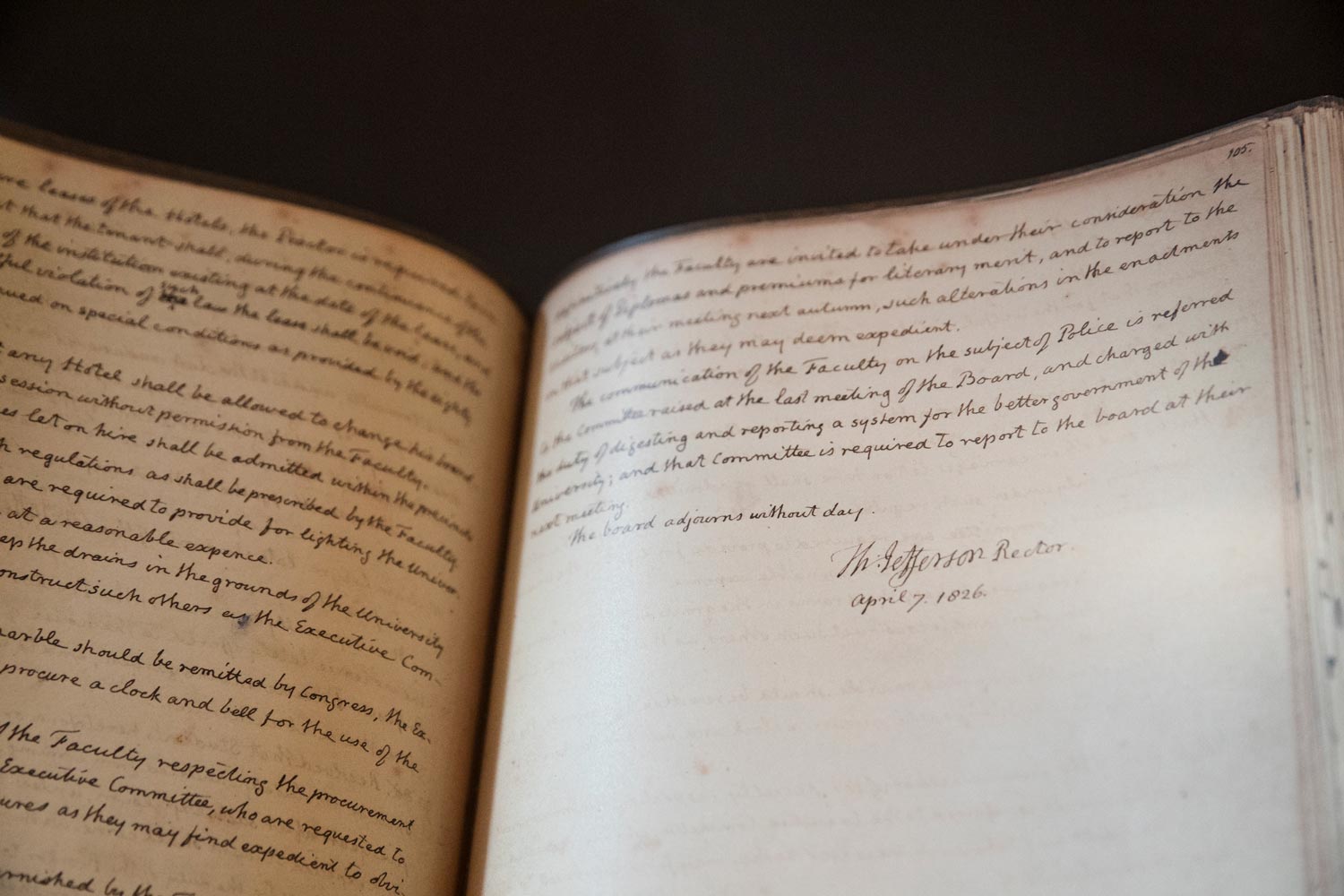

1. The First Minutes of the Board of Visitors

This minute book records the start of the University, as Jefferson, James Madison and other leaders set tuition, hired faculty members and honed day-to-day operations. Because Jefferson served as both rector and secretary, some of the book is written in his hand. The display is opened to the last entry that Jefferson wrote before he died. The next entry is mostly focused on his death on July 4, 1826.

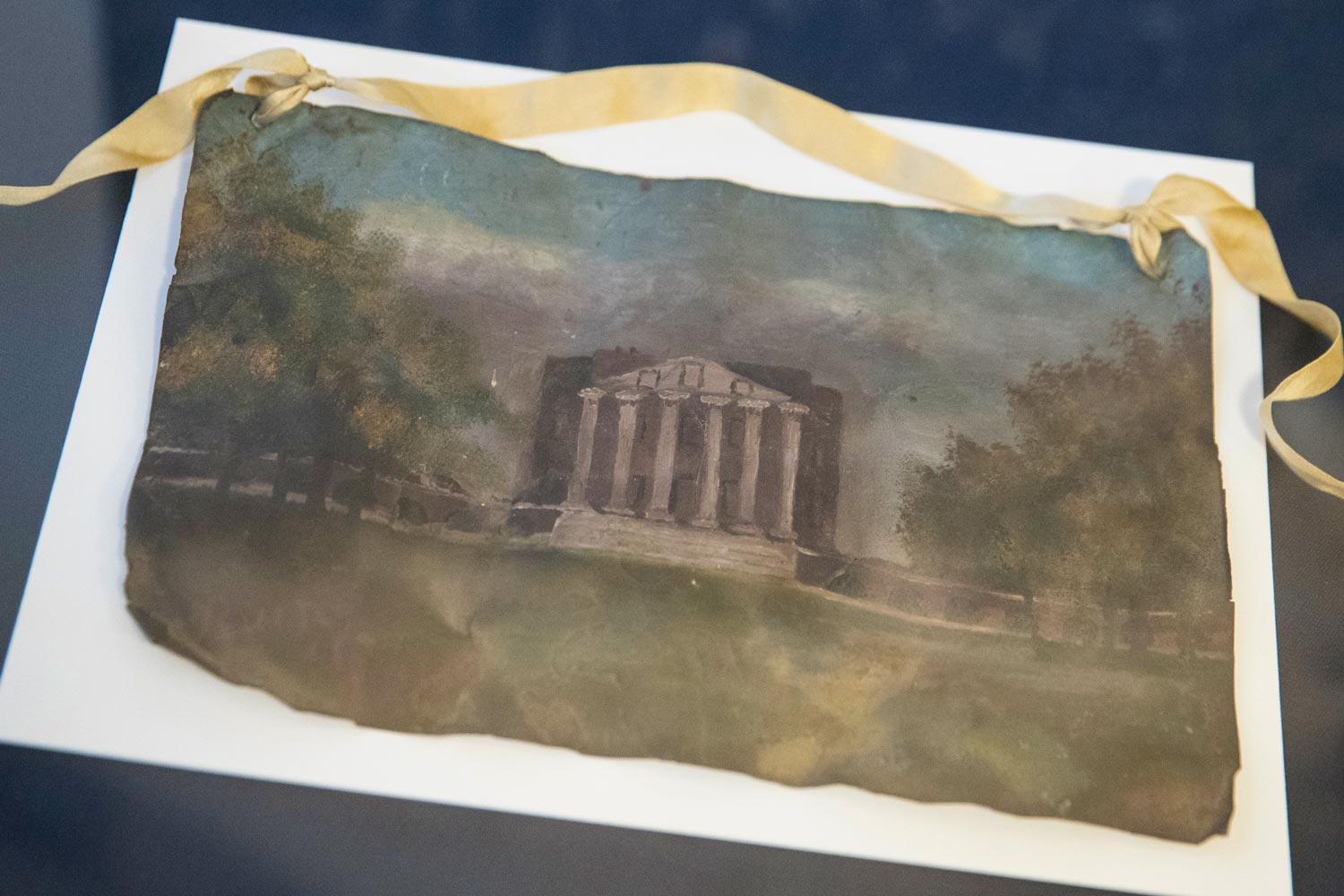

2. Original Rotunda Roof Tile, With Painting

The 1895 Rotunda fire was a defining moment for the young University and reduced its centerpiece to a scorched shell. An artist, known only as Miss Shuey, commemorated the fire and the original structure with a series of paintings like this one, painted on tin roof tiles that she collected from the ruins of the Rotunda and sold as souvenirs.

“The fire was a really interesting pivot point in the history of the University,” Wolfe said. “What really struck me was these pieces of the Rotunda – wrinkled and blackened by fire – were available for members of the public to just pick up.”

3. Photograph of Sally Cottrell Cole

This photograph of enslaved laborer Sally Cottrell Cole is one of just a few existing images of the enslaved men and women who worked at UVA. Cottrell, born around 1800 at Monticello, was hired out to UVA professor Thomas Hewitt Key and his wife, Sarah. Before the couple returned to their native England in 1827, they negotiated to purchase Cottrell. It is not clear if she was ever technically freed, but she lived as a free black woman after their departure and married a free black man, Reuben Cole, in 1846. After the Civil War, the couple returned to Albemarle County, where she died in 1875.

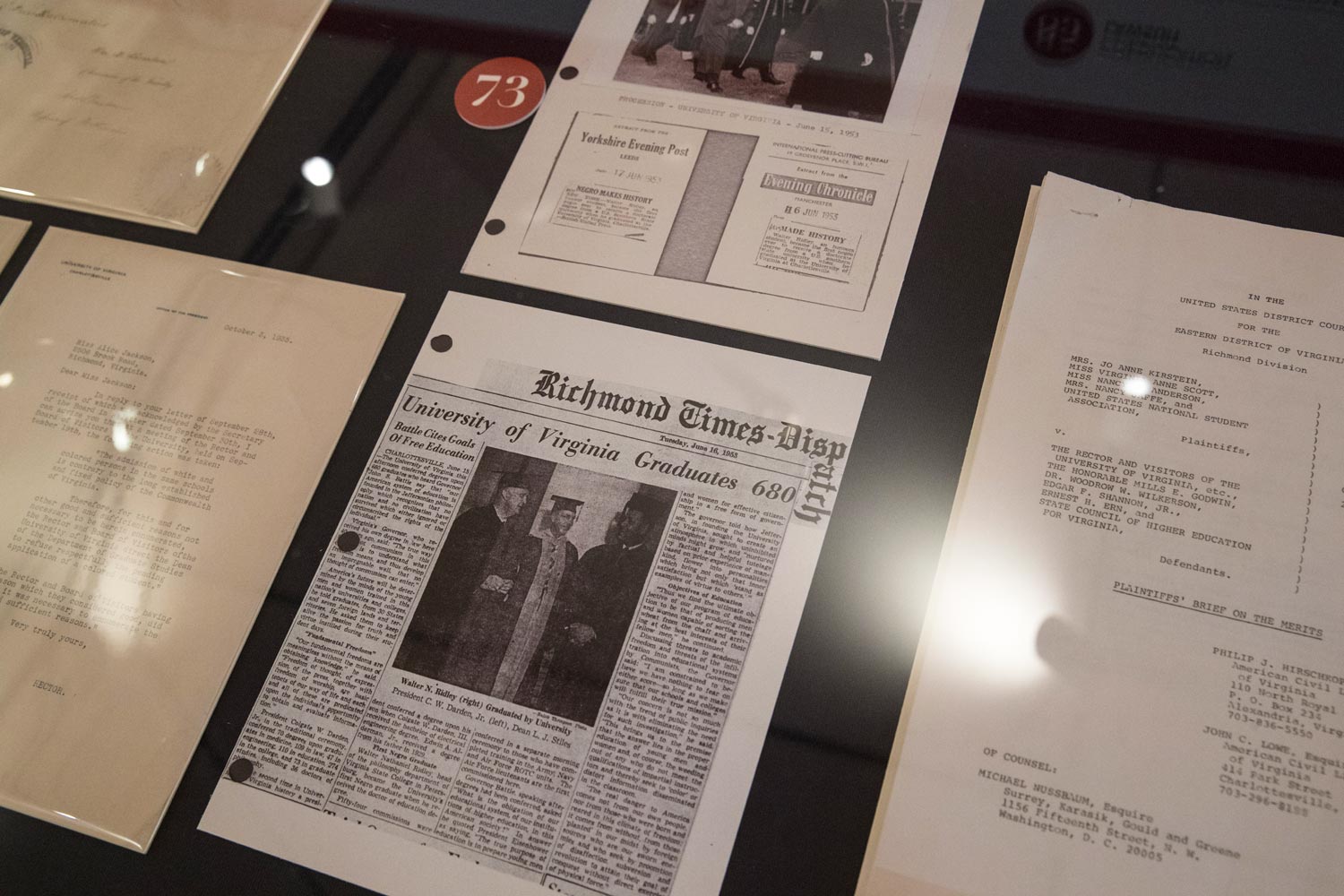

4. Walter Ridley Scrapbook

In one of the exhibition’s many powerful juxtapositions, Cole’s photograph is displayed near a scrapbook documenting the experiences of Walter N. Ridley, the first African-American student to earn a degree from the University and the first to receive a doctorate from a Southern state university.

Ridley earned a doctorate from the Curry School of Education in 1953. He was not the first African-American student to attend UVA, however. Danville native Gregory Swanson enrolled – after successfully suing for admission – at UVA’s School of Law in 1950, but withdrew after racist treatment from the larger University community.

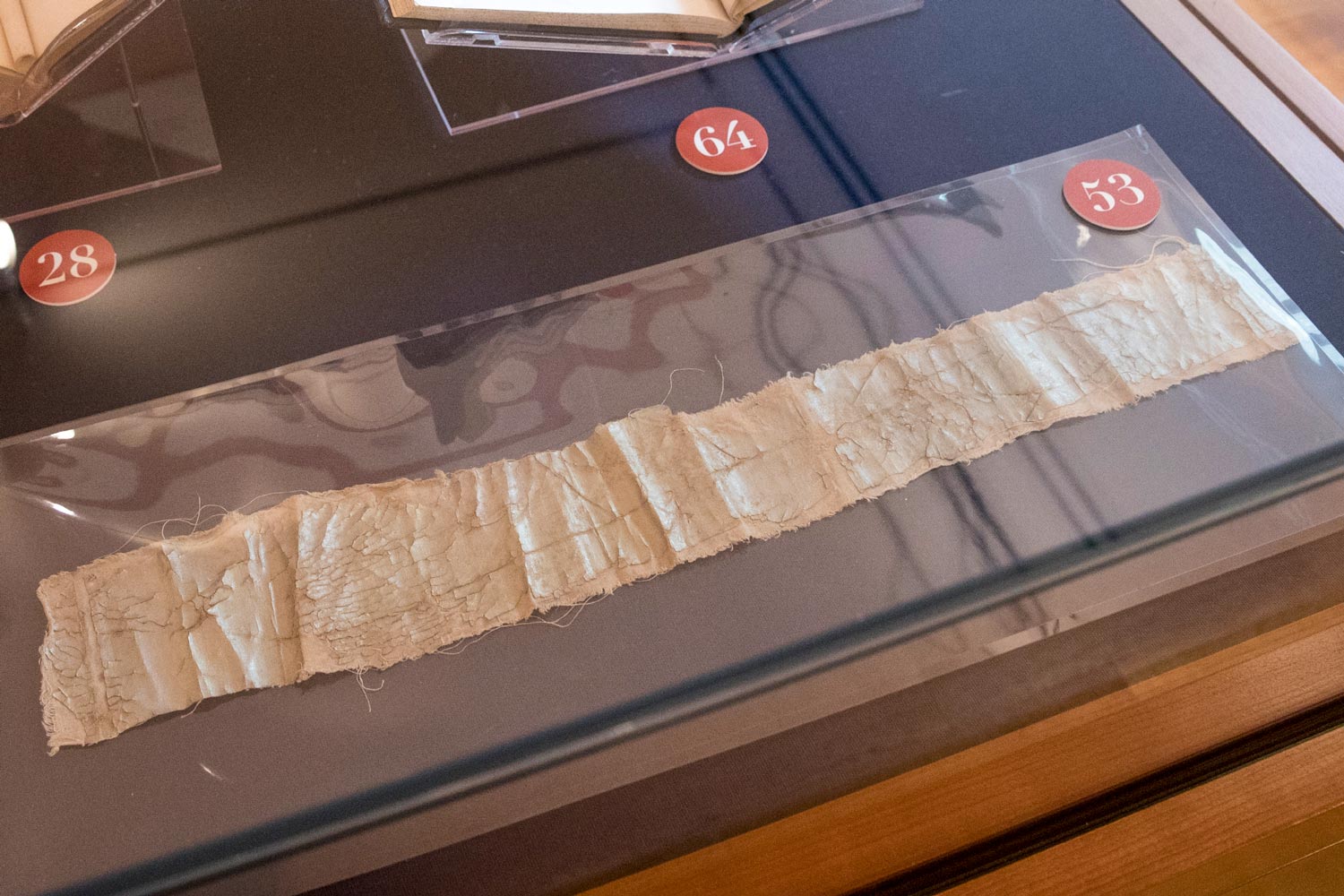

5. Strip From James R. McConnell’s Crashed Plane

James Rogers McConnell was the first in the University community to die during World War I. The former law student was shot down by German airmen in March 1917, when he was 30 years old. He joined the war effort in 1914, three years before the United States officially entered the fray. He first worked in the American Ambulance Field Service and later enlisted in the French military and joined what came to be known as the Lafayette Escadrille, a group of Americans who fought for France. After his death, the University commissioned “The Aviator” statue now standing near Clemons Library.

“McConnell was really active at UVA and was king of the Hotfoot Society at the time,” Wolfe said. “He even had a big red foot painted on his plane.”

6. Parachute Wedding Dress

During World War II, medical teams from UVA’s schools of Medicine and Nursing served in North Africa and Italy. In 1945, a nurse in one of those units – 1st Lt. Hilda “Frankie” Franklin –married a serviceman at one of those stations, Captain Richard P. Bell Jr. She wore this dress made from a silk parachute, likely with several layers underneath. After the war, the Bells returned to Virginia and settled in Staunton, where they raised four sons.

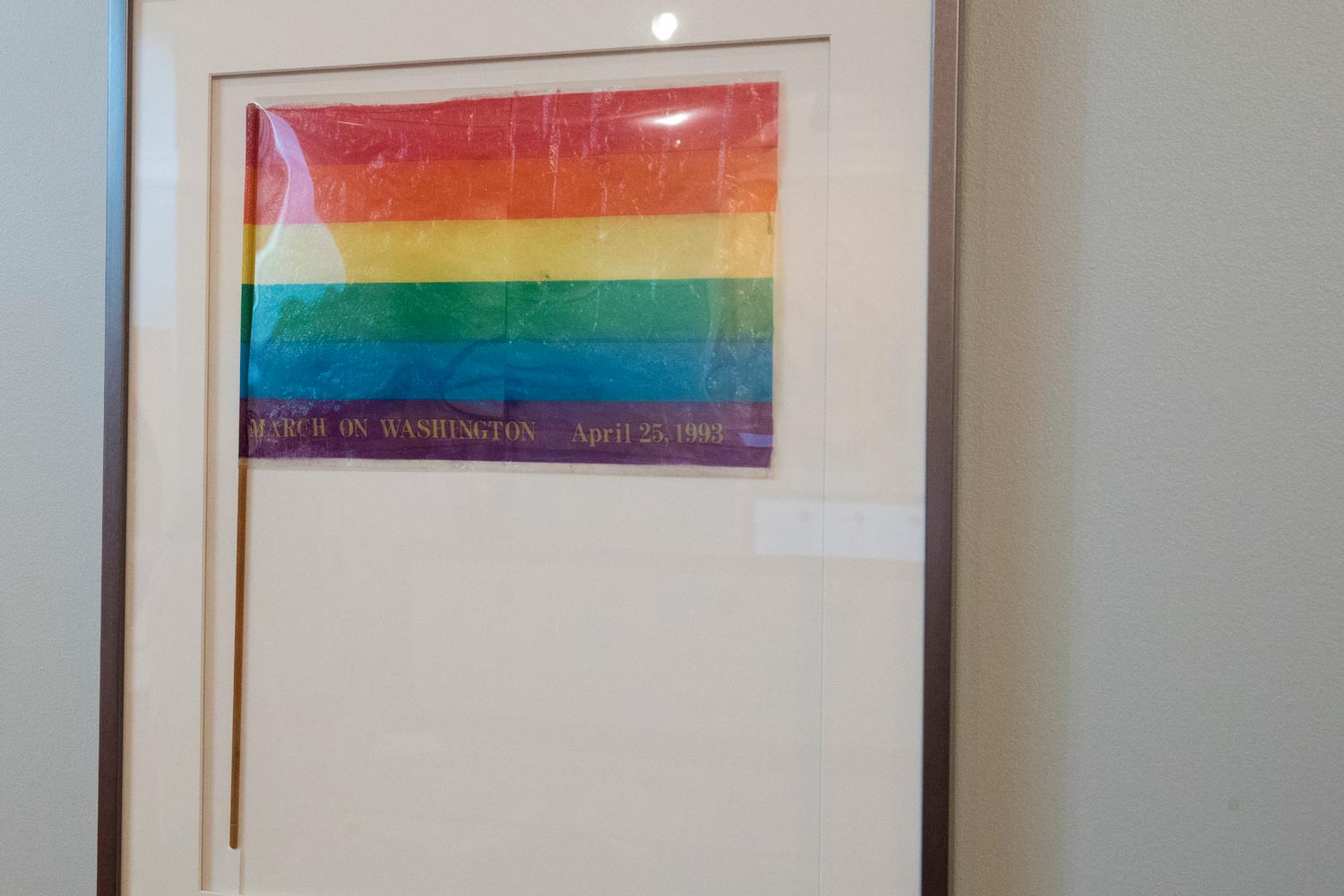

7. Bernard Mayes’ March on Washington Flag

Bernard Mayes was a professor of rhetoric and media studies who taught at UVA from 1984 to 1999. He had been a journalist for the BBC, founded America’s first suicide prevention hotline in San Francisco and sat on the first board of the National Public Radio. At UVA, Mayes helped found the University’s first group for gay and lesbian faculty and staff members, as well as an alumni group, the Serpentine Society. Their motto: “The walls aren’t straight and neither are we.”

“When you talk to those that knew him, it becomes clear that he was just a really remarkable person,” Wolfe said.

Mayes carried this flag in the 1993 March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation and kept it for the rest of his life as a memento.

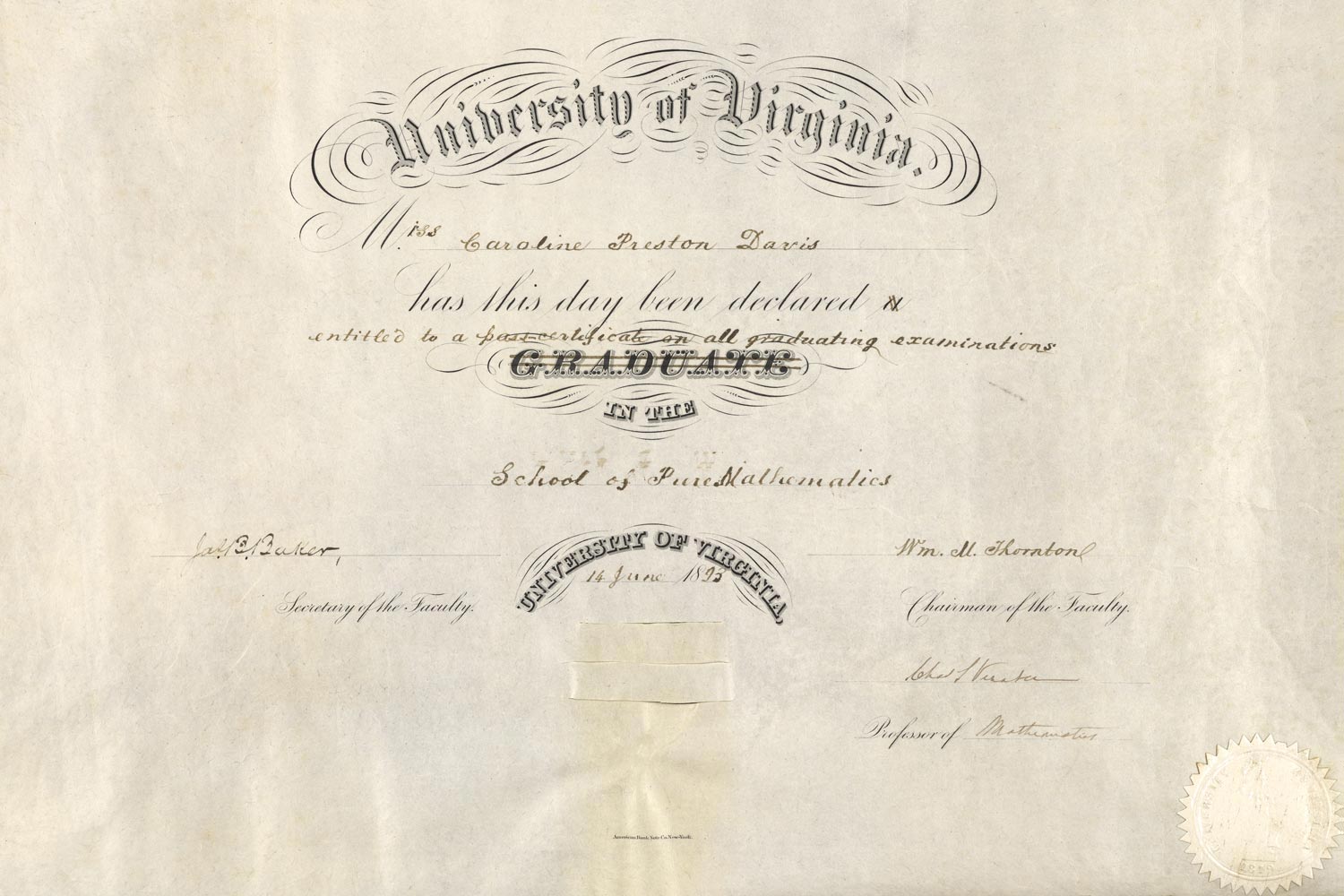

8. Pass Certificate of Caroline Preston Davis

On June 14, 1893, the University awarded Caroline Preston Davis a “pass certificate” noting that she had completed her mathematics exam with distinction. When Davis petitioned to enter UVA, the faculty decided to only educate white women of “good character” who would pay the same fees as men, but leave without a diploma. Davis, the granddaughter of law professor John A.G. Davis, whose murder may have spurred students to create the Honor Code, did well in her classes. Despite this, University officials would only give her a pass certificate, not a diploma, and even removed the University seal from the document. Shortly after she left the University, the faculty again decided to admit no women, regardless of circumstance.

9. First Women’s NCAA Championship

In 1970 – 77 years after Davis was awarded her pass certificate – UVA became fully co-educational and admitted 450 women to the College of Arts & Sciences. In 1977, UVA awarded an athletic scholarship to a woman for the first time; in 1981, the Cavalier women’s cross country team brought home the school’s first national title for a women’s team.

“Within a few years of arriving on Grounds, women were varsity athletes winning national championships, despite longstanding tradition saying this was not a place for them,” Wolfe said. “This trophy is at least a partial repudiation of that mindset.”

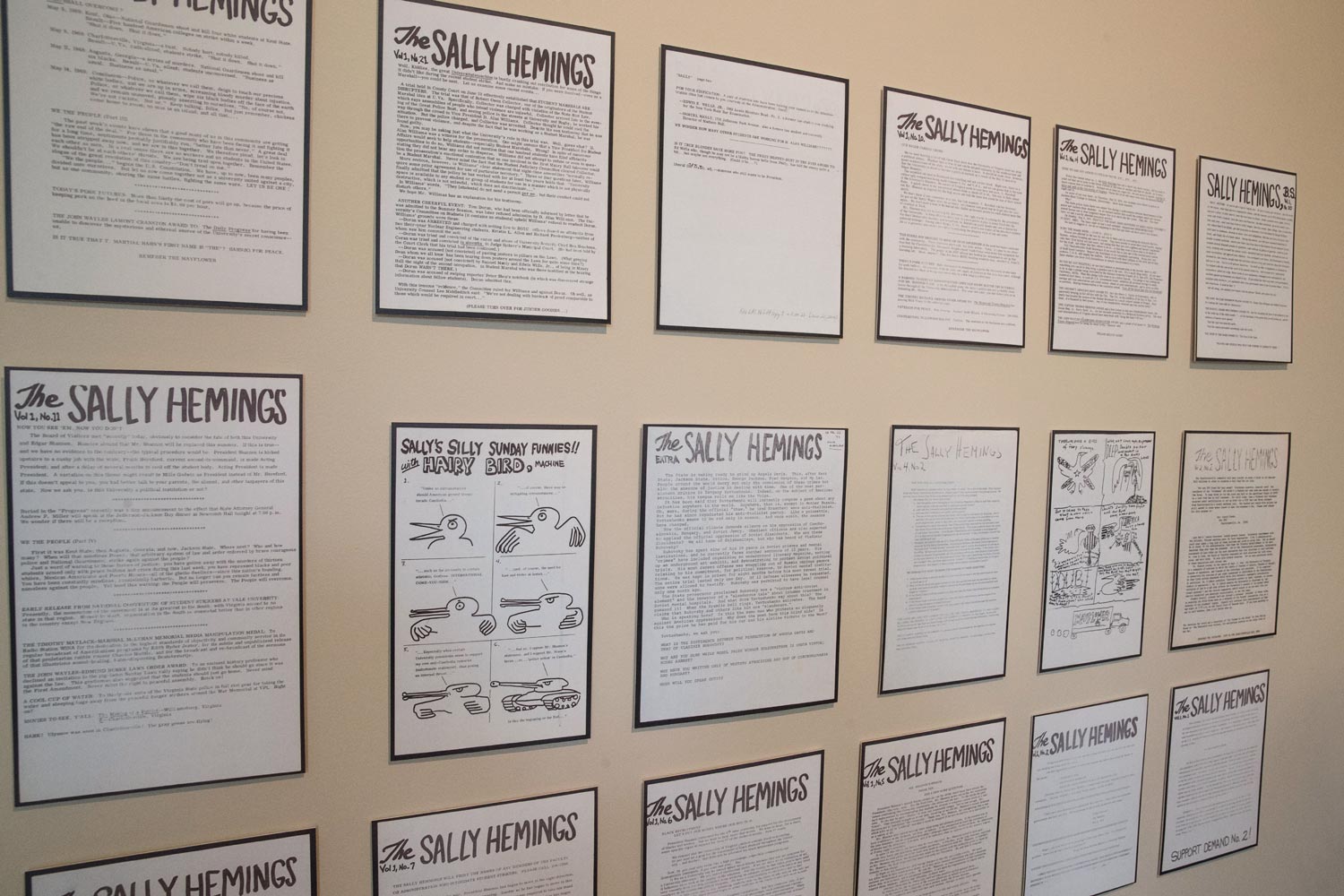

10. The Sally Hemings Underground Newsletter

In May 1970, in response to the shooting of four unarmed students at Kent State University by National Guardsmen, about 1,000 UVA students engaged in several days’ worth of rallies and marches on the Lawn and on Grounds. They joined students across the country in protesting expansion of the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War.

“It was a really dramatic moment in the history of the University,” Wolfe said. “There were marches up and down Rugby Road, state police came in, and so many people were arrested that giant Mayflower moving vans were operating as paddy wagons.”

As protests continued that week, students created and distributed hundreds of copies of an underground newspaper they dubbed “The Sally Hemings,” a dig at Jefferson. The newspaper chronicled the protests and used editorials and satire to discuss topics like the Vietnam War or the small proportion of black students at the University.

Visit the new exhibition to learn more about these objects and 90 others that represent different facets of the University’s history. The objects are displayed in the Special Collections Library and at 16 satellite sites around Grounds, with maps and pamphlets available and a mobile app coming soon. Details about visiting the exhibition can be found on its website. Visitors wishing to nominate additional objects can do so on the website, or on social media by tweeting to @rareUVA with #101object.

Media Contact

Article Information

August 25, 2017

/content/these-10-objects-and-new-exhibition-tell-powerful-story-about-uva