It’s rare that third-party outsiders can make an impact on the national political stage in the United States – but not unprecedented.

Under the rules of the Commission on Presidential Debates, presidential candidates must earn the support of at least 15 percent of voters in national polls in order to join the televised debates; recent reports suggest that Libertarian Party candidate Gary Johnson may be getting close. With less than two months to go until the first debate, he is hitting between 8 and 11 percent in various national polls – still well behind the nominees of the Democratic and Republican parties, but enough to make an impact on the outcome.

Barbara Perry, the director of presidential studies at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center and co-chair of the center’s Presidential Oral History program, recently discussed the impact third parties have had over the years and how they might affect the 2016 election.

Barbara Perry is the director of presidential studies at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center and co-chair of the Presidential Oral History program. (Photo by Amber Reichert)

“The very fact that our electoral system is a winner-take-all system discourages third parties,” she said. “So almost as soon as a splinter group goes off and plans their own platform, one of the major parties, or sometimes both, try to bring those people in. The big parties are like amoebas trying to go around the fringe groups and fold them in.”

Americans have already seen this once in 2016, as the Democratic Party has stretched to include many far-left-leaning Bernie Sanders supporters. It’s when the major parties are unwilling or unable to accept these differing viewpoints that third-party candidates step forward. Often their campaigns barely register on the national radar, but there are a few examples of times when they’ve captured just enough of the American electorate to make a difference.

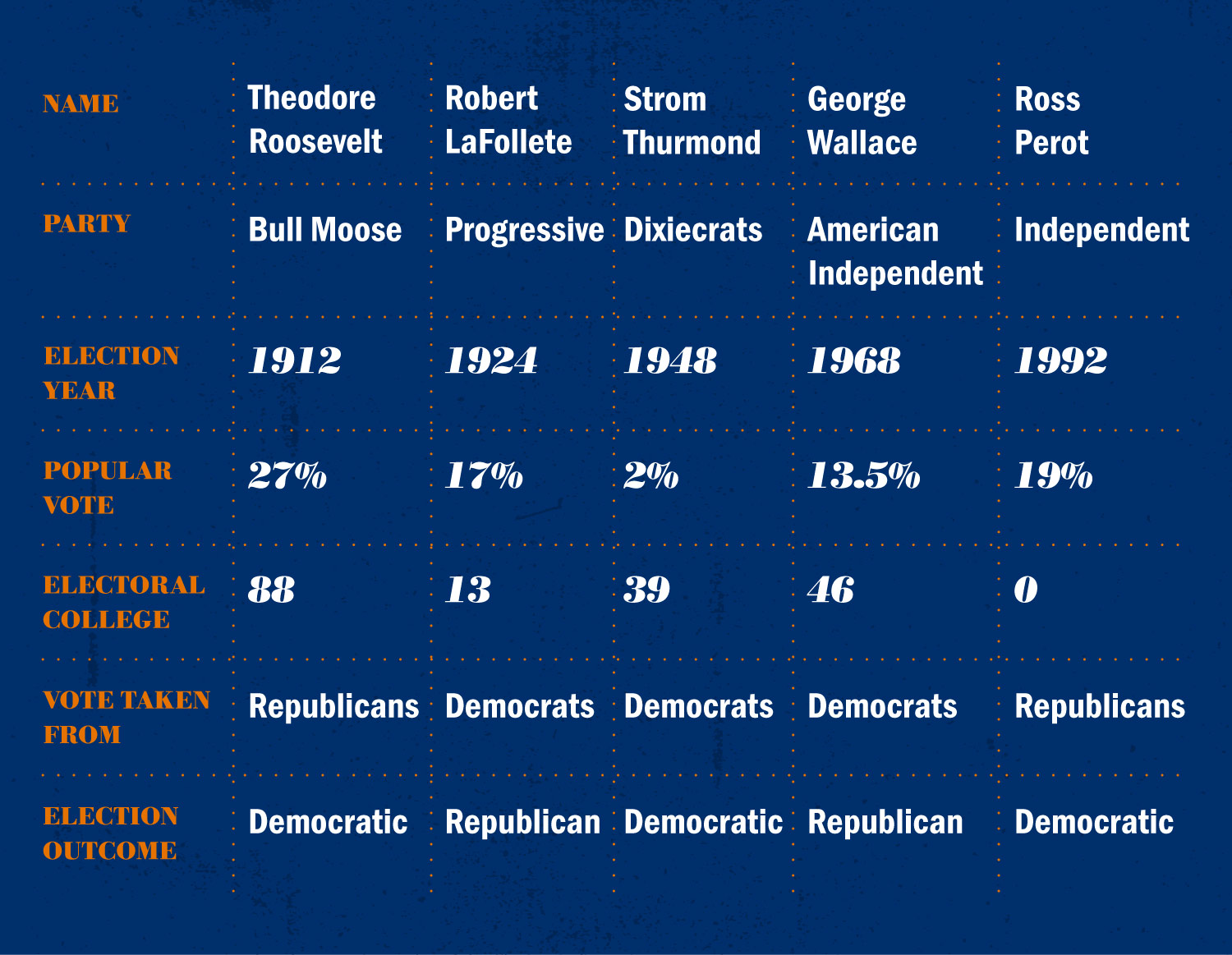

Theodore Roosevelt is the most successful third-party candidate in American history. After serving as president from 1901 to 1909 – first assuming office after the assassination of William McKinley and then winning the general election in 1904 – Roosevelt left the Republican Party to run again in 1912 and promote a more progressive platform through his Bull Moose Party.

He earned 27 percent of the vote, effectively splitting Republican voters between himself and sitting president William Howard Taft.

“That’s the most votes a third-party candidate has ever achieved,” Perry said. “It was pretty amazing, but it also splintered the Republican Party, causing [Democrat] Woodrow Wilson to win the election of 1912.”

The other two top third-party vote-earners of the 20th century are Robert Lafollete, who represented the Progressive Party in 1924, and Ross Perot, who ran as an independent in 1992. Lafollete took 17 percent of the popular vote, to the detriment of the Democratic Party, and Ross Perot hurt the Republicans with the 19 percent he garnered.

Perry explained the Perot is likely the best modern example of an impactful third-party candidate because his singular focus on a balanced budget forced both Republicans and Democrats to address that issue.

“When he got almost 19 percent of the vote, both Republicans and Democrats came together and balanced the budget,” she said. “The success of his campaign was like a tip from the American people saying, ‘You better pay attention to this. If you don’t pay attention, then something worse is going to happen to you in the next election.’”

While candidates like Perot may have forced changes in party agendas, it takes a major cultural and political schism for a third party to rise to the top and restructure the system. That last happened in the 1850s, when the anti-slavery movement fueled the formation of the Republican Party.

“It took the cataclysm of the Civil War and the breaking apart of the country to rejigger the parties,” Perry said. “There was not an ability on the part of Democrats – who were pro-slavery, we should add – or the Whigs, who existed after the Federalists, to take this anti-slavery group under their tent. Instead, the Whig Party died and then before the Civil War, the Republican Party rises up to become the other major party alongside the Democrats.”

Still, even small third-party candidates with limited success can impact the national outcome if they capture just the right percentage of votes in the right states. For this reason, Perry said disaffected Republicans who are leaning toward Gary Johnson over controversial Republican nominee Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders supporters who are leaning toward Green Party candidate Jill Stein over Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton have to ask themselves an important question: “Are you willing to accept that your third party vote may help someone you utterly disagree with?”

Perry added that Johnson and Stein still have a long way to go before they are even considered contenders for the presidential debate stage and the powerful exposure it offers, but it’s not out of the realm of possibility. Stein will have to overcome poll numbers hovering below 6 percent, but most pollsters have Johnson at least halfway to the required 15 percent.

“History doesn’t favor outside candidates, but common wisdom also doesn’t seem to apply this election,” Perry said. “If there’s ever a time when third-party candidate might make it into the debates, it’s this year.”

Media Contact

Article Information

August 3, 2016

/content/third-party-impact-american-politics