Soon-to-be triple ’Hoo Margaret Thornton was perusing the latest issue of her University of Virginia alumni magazine last summer – highlighting the “Retold” project, which celebrated the 50th anniversary of women being admitted as undergraduates at UVA – when one sentence caught her attention: “E. Louise Stokes Hunter (Educ ’53) becomes the first Black woman to earn a UVA degree.”

In her 15 years at UVA, Thornton had never heard of Hunter. So she did what we all do when confronted with curiosity: She started Googling.

Less than a year later, Thornton’s search has led to a renamed student research conference, an ongoing funded research project and a campaign to elevate Hunter’s legacy at UVA.

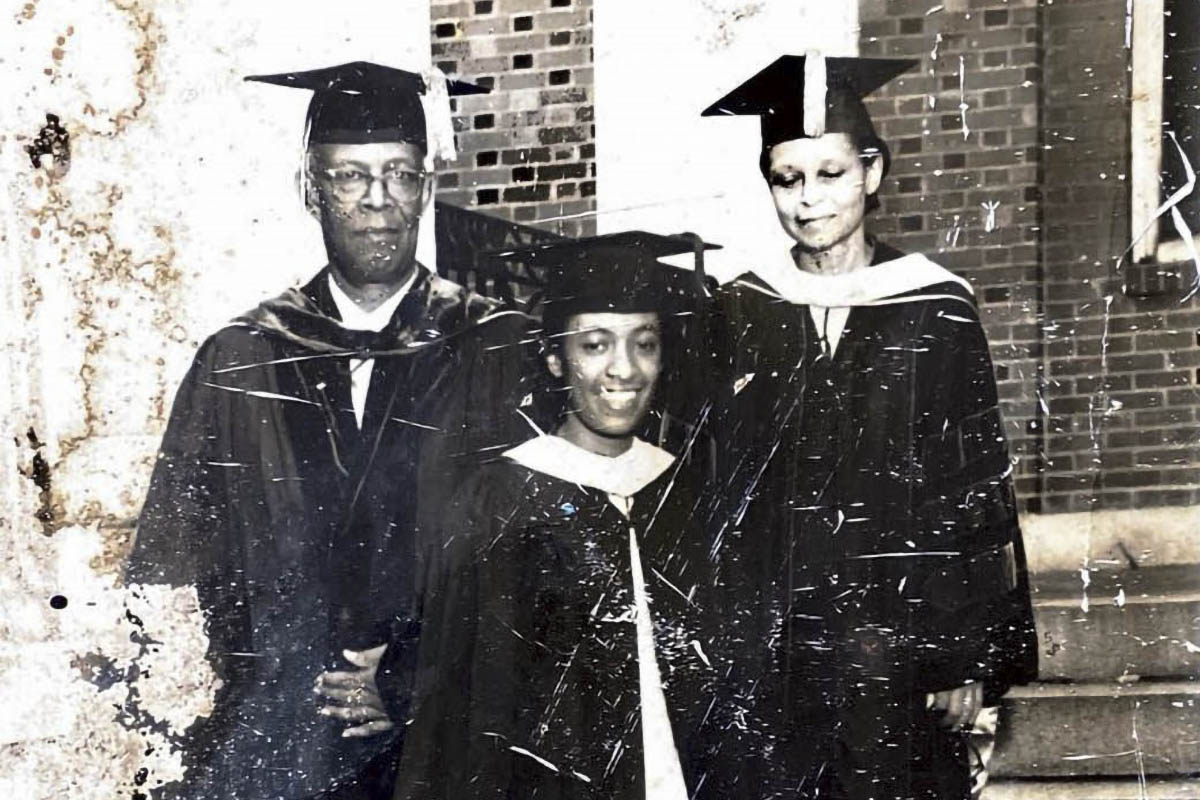

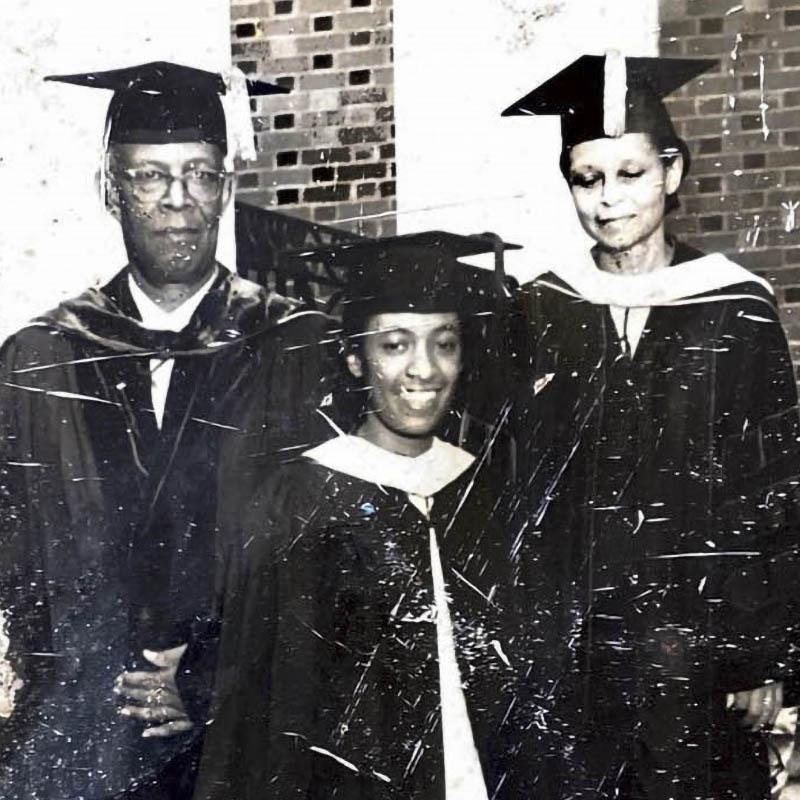

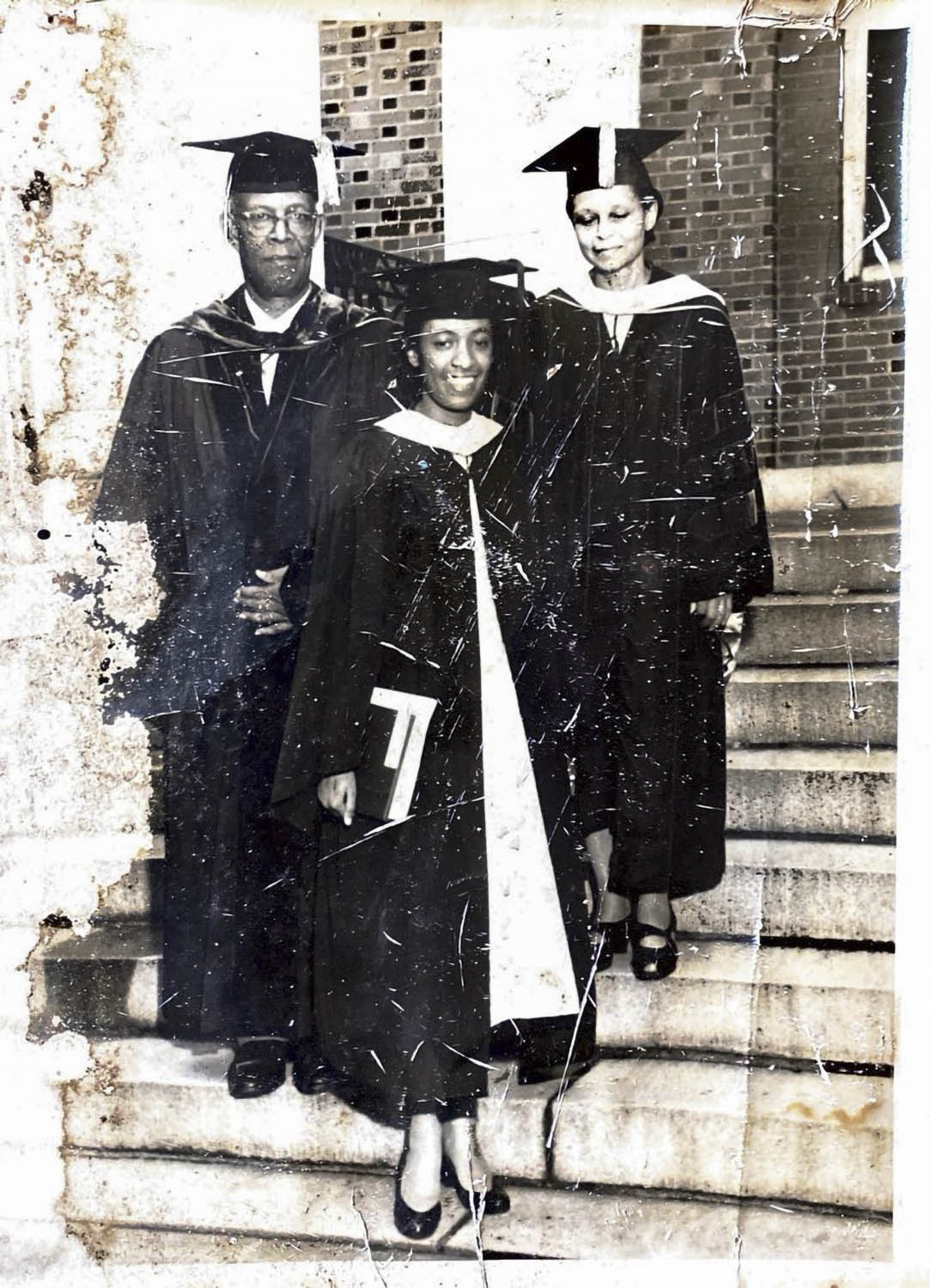

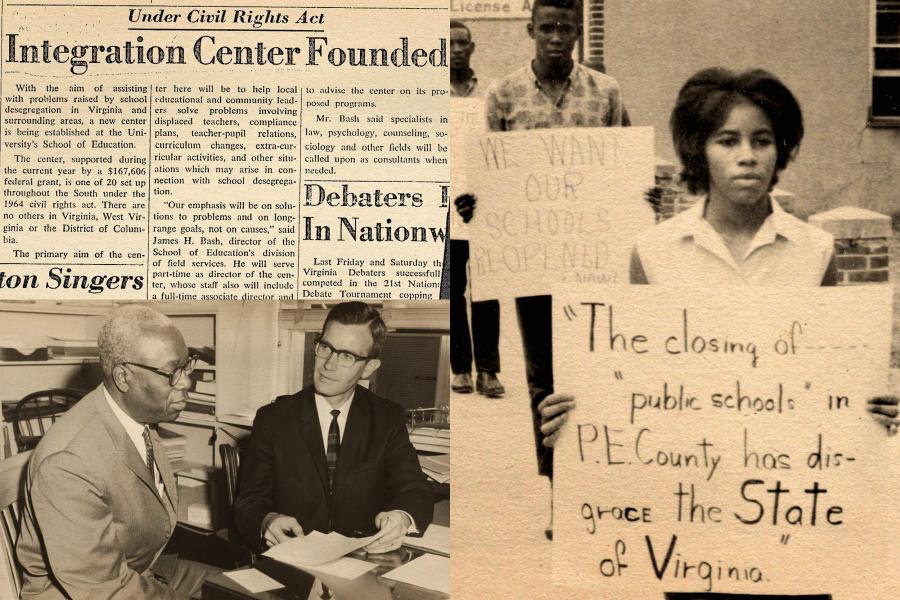

Hunter completed her doctorate in education from the School of Education and Human Development in 1953, just a few months after the University’s first Black graduate, Walter N. Ridley. She then spent a long career as a professor at Virginia State College (now Virginia State University), where she was known for her mentorship of Black students, particularly Black women studying math.

Until recently, however, not much else was known about her among the UVA community. Hunter died in 1988.