Walter N. Ridley would not have been a typical University of Virginia student in any year. He was 40 years old and married with two children. He held bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Howard University, and was on the faculty of Virginia State College.

Education Pioneer Walter N. Ridley Persisted in Pursuing Knowledge

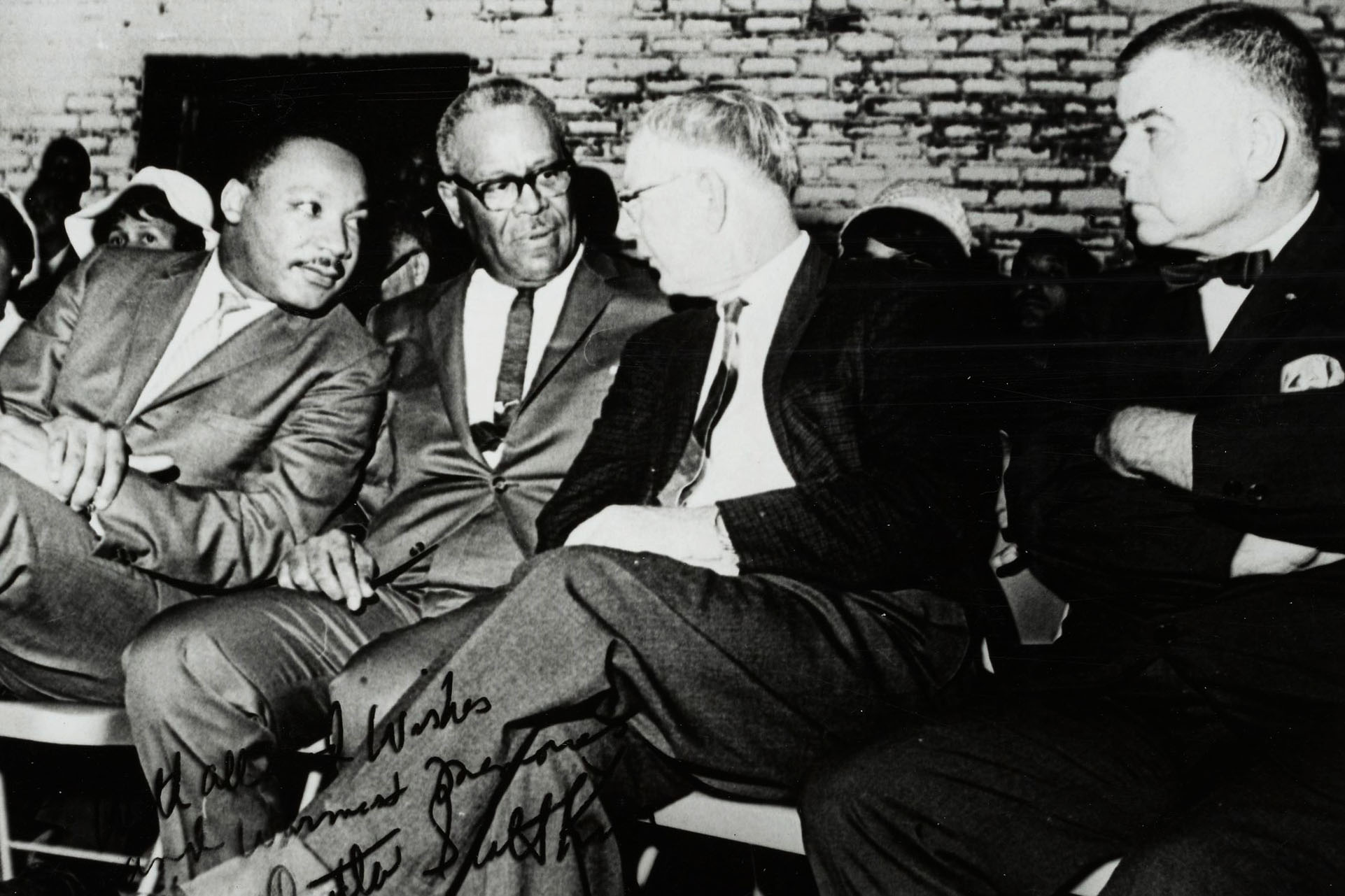

When Walter Ridley, second from left, was president of Elizabeth City State, he invited Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., left, to speak there. They were joined by state and local officials. (Photo courtesy Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

But the year was 1950. Despite his academic successes, UVA would not admit him to pursue a doctorate because he was African American.

After repeated attempts, he was finally accepted in 1951. Two years later, he earned his Ed.D. from UVA’s Curry Department of Education (before it became a school) – becoming the first Black student to graduate from UVA, as well as the first African American to earn a doctorate at any major white public university in the South.

Five years later, Ridley became president of Elizabeth City State Teachers College in North Carolina, making changes that included admitting its first white student and transforming the school into Elizabeth City State College (now University).

Last month, the UVA Board of Visitors voted to rename one of the education buildings in honor of him, changing Ruffner Hall to Ridley Hall.

Ridley’s granddaughter, Alyssa, and step-grandsons Carl and Mark Scheunemann said in a joint statement on behalf of Ridley’s descendants that they were “honored and excited” about the renaming: “Dr. and Mrs. Ridley would have been delighted, as would their daughter, Yolanda Ridley Scheunemann, and their son, Don Ridley.”

“Walter Ridley was an extraordinary educator and leader,” said Robert Pianta, dean of the Curry School of Education and Human Development. “His life and career demonstrate the values, conviction and commitment to action and equality that serve as models for the work we do as a school of education and human development. Recognizing his legacy and making visible his contributions and courage are just one way that we can carry his work forward.”

Early Details of His Life

Ridley was born April 1, 1910, one of eight children of Mary Haywood Ridley and John Hoskins Ridley; John Ridley’s father had been enslaved in North Carolina and eventually bought his freedom and his wife’s. Walter Ridley’s parents moved to Newport News, where John Ridley worked in shipbuilding, rising through the ranks and then cofounding Crown Savings Bank. Mary Ridley, a musician, taught piano.

Walter Ridley earned a bachelor’s degree, cum laude, in psychology and a master’s in educational administration from Howard University in 1931 and ’33, respectively. Two years later, he joined Virginia State College (now Virginia State University) in Petersburg as a psychology professor and director of extension.

In 1939, he married another trailblazer, Henrietta Bonaparte, who was the only Black student to graduate in her class from Macalaster College in St. Paul, Minnesota. (And yes, she was a distant descendant of Napoleon Bonaparte.)

Going to UVA

When Ridley, determined to pursue a doctoral degree, applied to UVA in the 1940s and was denied, he wrote back, “My father has paid taxes in this state since before I was born and I am entitled to study here,” according to the biography accompanying some of his papers housed at Elizabeth City State University.

Under the commonwealth’s laws segregating education of Black and white students, Virginia was willing to pay for Ridley to go to another university out of state to pursue his doctorate. He attended the University of Minnesota and The Ohio State University and was researching audiovisual materials, but developed a hemorrhage in his eye and was advised to stop that research. He returned to work at Virginia State.

The lawsuit of another potential Black student, Gregory Swanson, enabled Ridley to push on the door of admission again in 1950. Swanson, with the support of NAACP lawyers, won his case and was admitted to the UVA School of Law for a master’s program (although he left before earning that degree).

At that time, University administrators, beginning to grapple with integration, decided to recruit African American students deemed “highly likely to be successful.” Education Dean Lindley Stiles, a proponent of desegregation, was visiting Virginia State when he met Ridley and encouraged him to reapply to UVA. Ridley was accepted in the fall of 1951, changing UVA history when he walked the Lawn two years later, graduating with high honors and as a member of Kappa Delta Pi honor society.

Because he was commuting from Petersburg, Ridley did not encounter the room and board problems that Black students who came later faced. As his papers note, his time at UVA did not appear to be marked by open resistance to his presence, or the violence that occurred several years later when other African Americans integrated other Southern schools. His pioneering achievement in desegregating the University, however, was noted in the national and international press.

When the Curry School published an interview with Ridley in its newsletter 25 years later, he said he had always been treated with respect at the University. Both Black employees and white University students told him on multiple occasions they were proud of his achievement, he said.

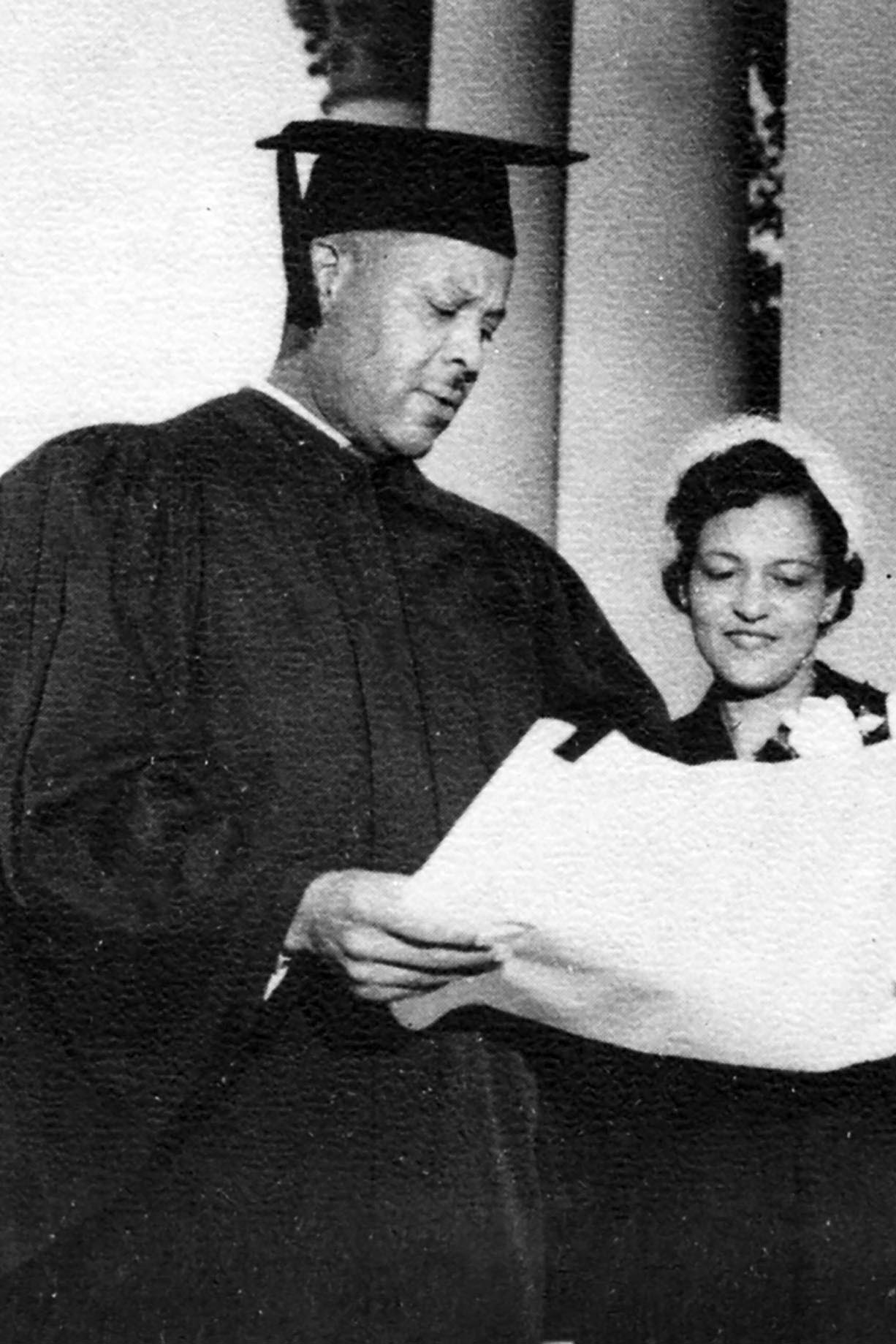

Ridley earned a Ed.D. from UVA in 1953, before Brown v. Board of Education brought desegregation to public schools. (Photo courtesy of UVA Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

In a 2008 documentary film made about Ridley, his daughter, Yolanda Ridley Scheunemann, and UVA alumna Teresa Bryce told the story of African American janitors surreptitiously watching Ridley through a window as he demonstrated a statistics problem at the blackboard in class. Apparently he felt that eerie sense that he was being watched, but didn’t know who was there until he left the building. Scheunemann said the men parted to let him pass and said, “Oh, Mr. Ridley, we’re so glad you’re here.”

Scheunemann, who died in 2011 at age 69, remembered her father’s graduation on the Lawn, her mother’s sense of happiness and pride, and that the crowd noticeably applauded when her father received his degree. (Scheunemann’s younger brother, Don Leroy, who was there, too, died in 2004.)

“It was just a peaceful, beautiful, fulfilled day,” she recalled.

Education Career

Ridley not only broke the color barrier in enrolling at UVA, but also continued to enhance higher education for African Americans throughout his career.

He returned to Virginia State College where he had been teaching since 1936, and after a total of 21 years there, served for a year in 1957 as academic dean of St. Paul’s College in Lawrenceville, Virginia. Then, in 1958, he was hired as president of Elizabeth City State Teachers College, a position he held for 10 years and “regarded as his most significant academic work,” according to his biography.

Those who worked with him recalled a strong leader with a bold vision who had exacting principles as he worked to improve the academic standing of this small institution of higher education, especially during the growing civil rights movement.

“The challenge to move forward was there,” said Evelyn A. Johnson, a leading professor at Elizabeth City State College at the time. “This strong, courageous, fearless man began planning, driving and pushing obstacles aside with alacrity, as if every moment could not and should not be lost. A perfectionist at heart, he was admired by some and disliked by others.”

He didn’t back down in his plans for improvement and quest for equity in education, at Elizabeth City State or for African Americans generally. He pushed for increased funding and was outspoken in his views, which wasn’t always appreciated by the North Carolina Board of Higher Education. Some say that he was pressured to resign.

“Schools are not equal in a democracy,” Ridley said in a speech to the student body in the early 1960s. “Southern schools are not equal to Northern schools; rural schools are not equal to city schools; and Negro schools are not equal to white schools. ... We must catch up to the other schools, and all students must have the opportunity to take responsibilities because this is a part of a democracy.”

Under his leadership, the college grew significantly, with the construction of new buildings and expansion of academic offerings, from one major in elementary education to 13 majors, and dropping “Teachers” from its name. Student enrollment at the college jumped from 400 in 1958 to more than 1,000 by 1965. For the first time, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools granted full accreditation in 1961. His efforts laid the groundwork for the college to join the University of North Carolina system in 1969.

“All students must have the opportunity to take responsibilities because this is a part of a democracy.” — Walter Ridley

Wanting to spend the end of his career in the classroom, he told his granddaughter, he joined the faculty at West Chester University near Philadelphia, chairing the Department of Secondary Education and Professional Studies and teaching until retiring around 1980.

Ridley was active not only in participating in professional education organizations, but also in advancing them. Before 1966, national professional organizations for college and university educators were segregated. He was a member of the National Association of Black Educators in Colleges and Universities and also the American Teachers Association between 1941 and 1966, holding posts as president, treasurer and trustee of the latter group. Then he served on the commission that combined the American Teachers Association and the National Education Association. At the time of the merger in 1966, he was the keynote speaker at the historic merger dinner and was presented the Meritorious Service Award for 25 years as a national officer.

Among his other affiliations and areas of service, he was a charter member of the U.S. Commission on UNESCO in 1946 and in 1964 traveled to Pakistan, India, Hong Kong and Japan with the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education, sponsored by the U.S. State Department. He served on the Antioch (Ohio) College Board of Trustees, and was a member of the corporation of the Save the Children Federation, Virginia Association of Mental Health, Virginia Academy of Science, American Psychological Association and Association of University Professors. He was a 10-year member of the CIAA Presidents Council, heading it for four years.

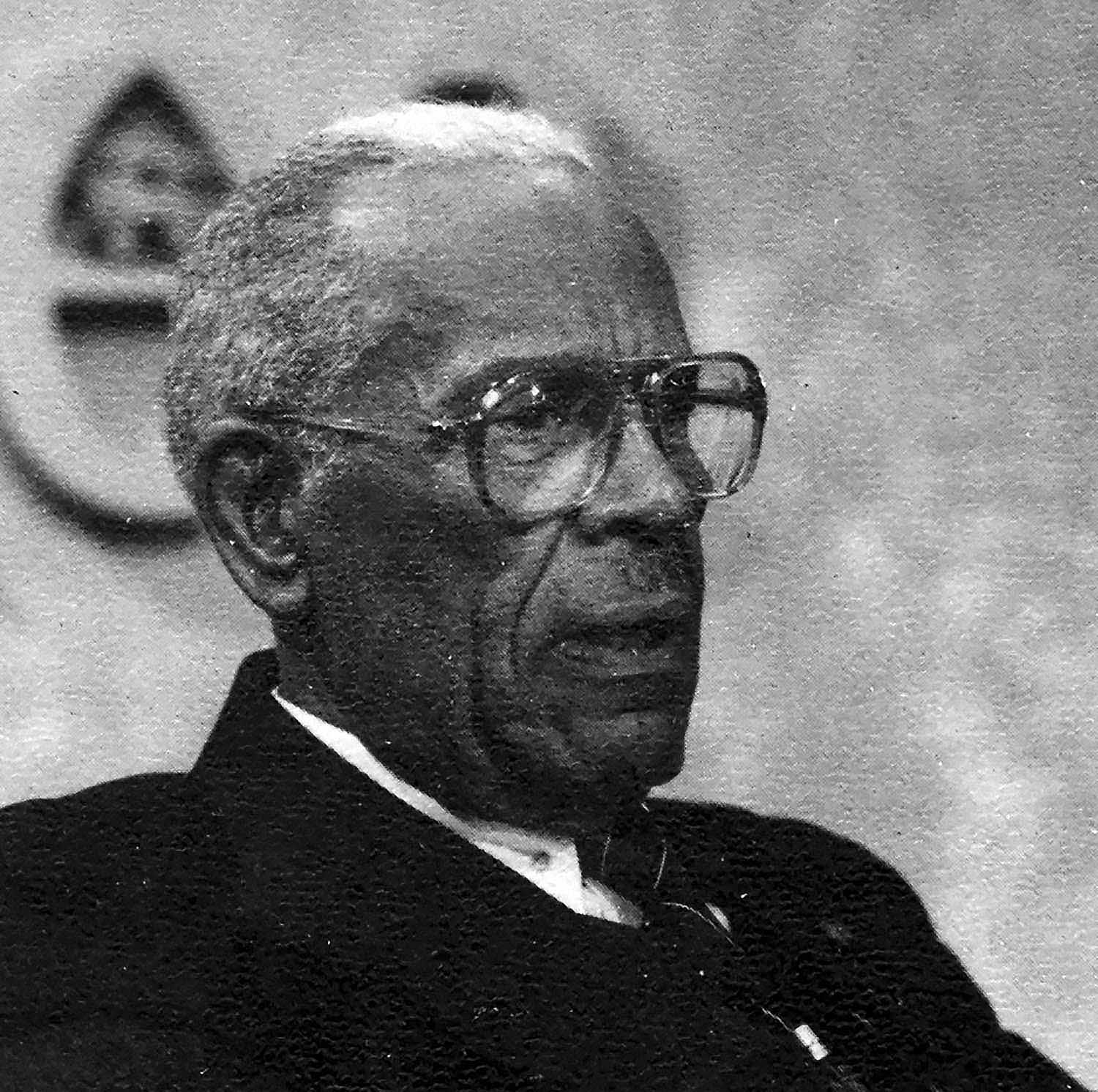

In 1988, Elizabeth City State University named Ridley president emeritus. That same year, he was recognized as a distinguished alumnus on the Curry School Foundation’s Education Day. The UVA education school created and named an annual lecture series for him in 2006.

Ridley the Man, and His Legacy

“The value my grandfather placed on education was a given,” his granddaughter, Alyssa Scheunemann, wrote in email. “He believed it was essential to the well-being of a human being, not just for economic reasons, but as a matter of human development.”

Ridley was recognized as a distinguished alumnus on the Curry School Foundation’s Education Day in 1988. (Photo courtesy of Curry School)

When Ridley’s daughter Yolanda married Henry Scheunemann in 1968, Scheunemann had two sons, Mark and Carl, from a previous marriage. Yolanda and Henry had two children of their own: a son, David, born in 1974, who died in 1992, and Alyssa, born in 1979.

At the time they married, being a biracial couple was still rare, Mark said recently by phone from Chicago, but of course, he didn’t know that at the time, being only 8 years old. Mark said he was vaguely aware that something was different, while at the same time, growing up with divorced parents was also unusual. He hadn’t had a grandfather before this, so as a child, he was glad. This friendly man seemed to accept the role automatically, Mark realized as an adult, he said.

Alyssa, who lives in Barryville, New York, has been keeper of the family history. She said they saw their grandparents a few times a year for holidays, summer visits and other important events.

Alyssa and Mark remembered the photos hung in their house that showed their grandfather with well-known civil rights and political leaders. The Ridleys were active in civil rights activities, invited Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to speak at Elizabeth City State College and hosted him in their home.

She remembered her grandfather talking about being involved with the NAACP, considered a controversial and even radical organization in those days.

“In the popular imagination, you can almost miss how much tension there was in the country at the time,” she wrote. “I have always been aware from the way my grandfather talked about it that the air in the country was thick with tension, and that it was not really very welcome. … At the time, being associated with the NAACP put his life at risk.

“Also, I really got a sense that within the movement there was a diversity of thought and different ideas about the direction of the movement, what methods should be used to exert pressure, etc.,” she said.

Alyssa was still in high school when Ridley died, but she recalled another groundbreaking decision he made: “Perhaps the action my grandfather took that is most impressed upon my consciousness is the integration of Elizabeth City State College – which he had zero hesitation about.

“When a white student applied, the question of what to do or how to handle it was brought to him as a big or weighty question. He responded resolutely and without hesitation that the institution would not be visiting the ugliness of segregation, which had been so painful and damaging to blacks, on whites. He refused to be driven by resentment or retaliation. He was focused on bringing this kind of violence to an end – for everyone.”

She described his legacy for her personally: “It is a legacy of excellence, patience, perseverance, steadiness.”

Carl remembered having a conversation later in his step-grandfather’s life when the topic came up of the “two schools” of the civil rights movement, the non-violent path of King and the more radical “fight back” view, personified by Malcom X and others.

“I asked him [Ridley] if he had ever been in a position where he felt he had to stand and perhaps actually fight as a Black man. His response was so memorable,” Carl wrote in an email.

His grandfather said, “That was not and would not be MY way, Carl. I would never do that. My way was to SHOW people the truth.”

He did not elaborate further, Carl said.

The three remembered their grandfather as a distinguished man who was strong and gentle, humble and serious, and enjoyed telling funny stories.

Walter Ridley, 86, died on Sept. 26, 1996, in West Chester.

The Ridley Scholars Program

Likely the most far-reaching effort to recognize Ridley’s legacy at UVA began when the University’s earliest Black alumni gathered for the first reunion of this group in 1987, Ridley among them. It was the first time the University had invited him back and honored his achievements, along with this hardy group of alums from the 1950s and ’60s.

“Walter Ridley believed education was essential to the well-being of a human being, not just for economic reasons, but as a matter of human development.”— granddaughter Alyssa Scheunemann

John Merchant, who became the first Black graduate of the School of Law in 1958 (and who died this March), suggested that a scholarship fund be created for promising Black students and named in Ridley’s honor. Since then, hundreds of alumni, parents and friends have contributed to the program, the first such scholarship board initiated by Black alumni at their university. To date, more than 300 young men and women have benefited from the expanding suite of scholarships and programs.

“The Ridley Scholars Program has been building to provide a network for merit-based Black scholars across Grounds to fulfill a truly supportive and enriching experience,” said Marcus L. Martin Jr., director of development for the program at the UVA Alumni Association. “As we work with the Curry School of Education and Human Development on future celebrations and events, the name change [to Ridley Hall] will serve as a great testament to UVA’s desire for progress.”

The latest addition to the program focuses on leadership. Partnering with the National Outdoor Leadership School, a nonprofit dedicated to teaching wilderness technical and medical skills, the Ridley Scholar Experience enables Ridley Scholars to receive a full-tuition scholarship on any expedition of their choosing.

“Going forward, this focus strongly aligns with our mission,” Martin said, “to positively impact the experience and opportunities for Black students here on Grounds through the Ridley Scholars Program.”

Media Contacts

University News Associate Office of University Communications

anneb@virginia.edu (434) 924-6861