__________________________

Notes

1. “Editor’s Drawer,” Virginia University Magazine, Vol. VI, No. 1, December 1867, p. 45.

2. “The Future Rulers of the World,” Virginia University Magazine, Vol. VI, No. 5, April 1868, p. 211.

3. “Editor’s Drawer,” Virginia University Magazine, Vol. VI, No. 5, April 1868, p. 239.

4. “Athletic Sports,” Virginia University Magazine, Vol. VII, No. 5-6, Feb-March 1869, p. 282; “Collegiana,” Virginia University Magazine, Vol. X, No. 4, January 1872, p. 215; “Editor’s Table,” Virginia University Magazine, Vol. XII, No. 4, January 1874, p. 267; “Collegiana,” Virginia University Magazine, Vol. XI, No. 4, January 1873, p. 215.

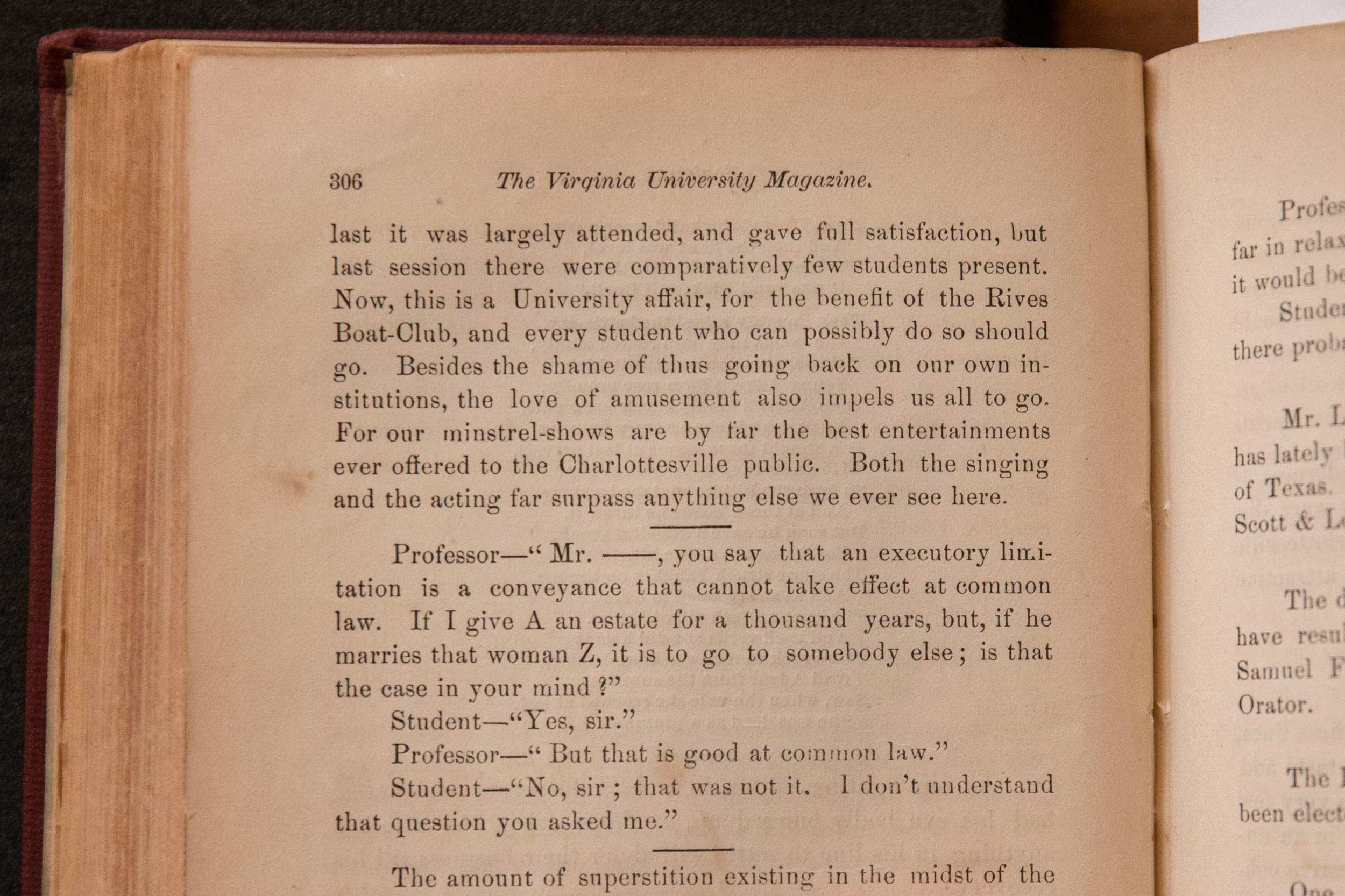

5. “Collegiana,” Virginia University Magazine, Vol. XVIII, No. 5, February 1879, p. 305.

6. Eric Lott, Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 3.

7. William John Mahar, Behind the Burnt Cork Mask: Early Blackface Minstrelsy and Antebellum American Popular Culture, Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1999, p. 1.

8. “Collegiana,” Virginia University Magazine, Vol. XVIII, No. 5, February 1879, p. 306.

9. “The New Time: From Amid the Shadows of the Old. In Two Parts—Part I,” Virginia University Magazine, New Series Vol. XII, No. 1, November 1882, p. 80.

10. “Plea for a Race Distinction in the United States, Virginia University Magazine, New Series, Vol. XXIII, No. 1, October 1883, p. 19.

11. “Collegiana,” Virginia University Magazine, New Series, Vol. XIII, No. 7, April 1884, p. 433.

12. “The Darkeyad,” Virginia University Magazine, New Series, New Series, Vol. XXIV, No. 8, p. 482-484.

13. “Editor’s Table,” Jefferson Monument Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 8, May 1850, p. 262; Virginia University Magazine, January 1870, p. 41 and 48. See also William Ramsey Letter to Father, undated, University of Virginia Special Collections Library (Ramsey was a student from 1883-1887).

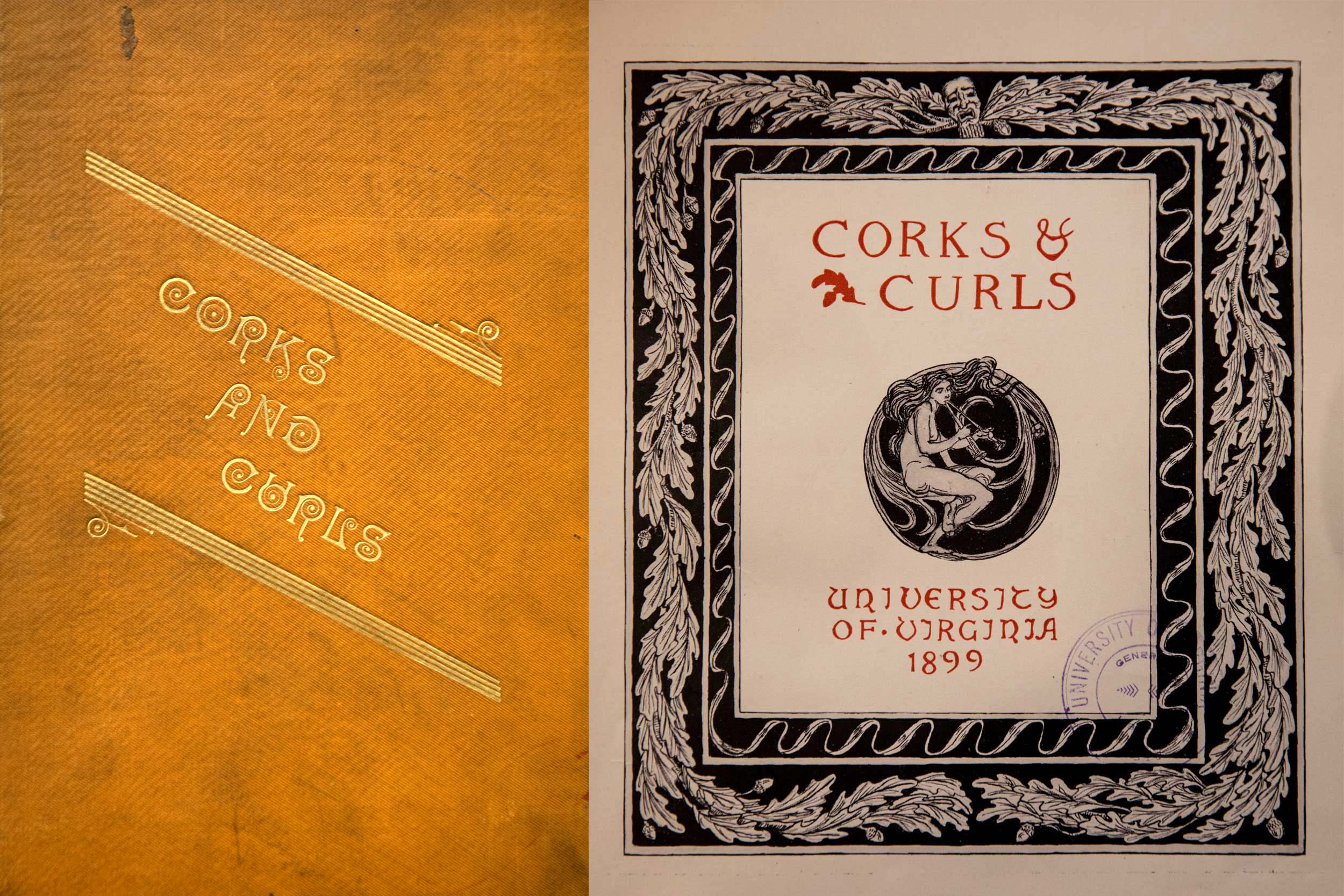

14. University of Virginia Corks and Curls, 1888, p. 11-12.

15. Brian Roberts, Blackface Nation: Race, Reform, and Identity in American Popular Music, 1812-1925. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017), 20.

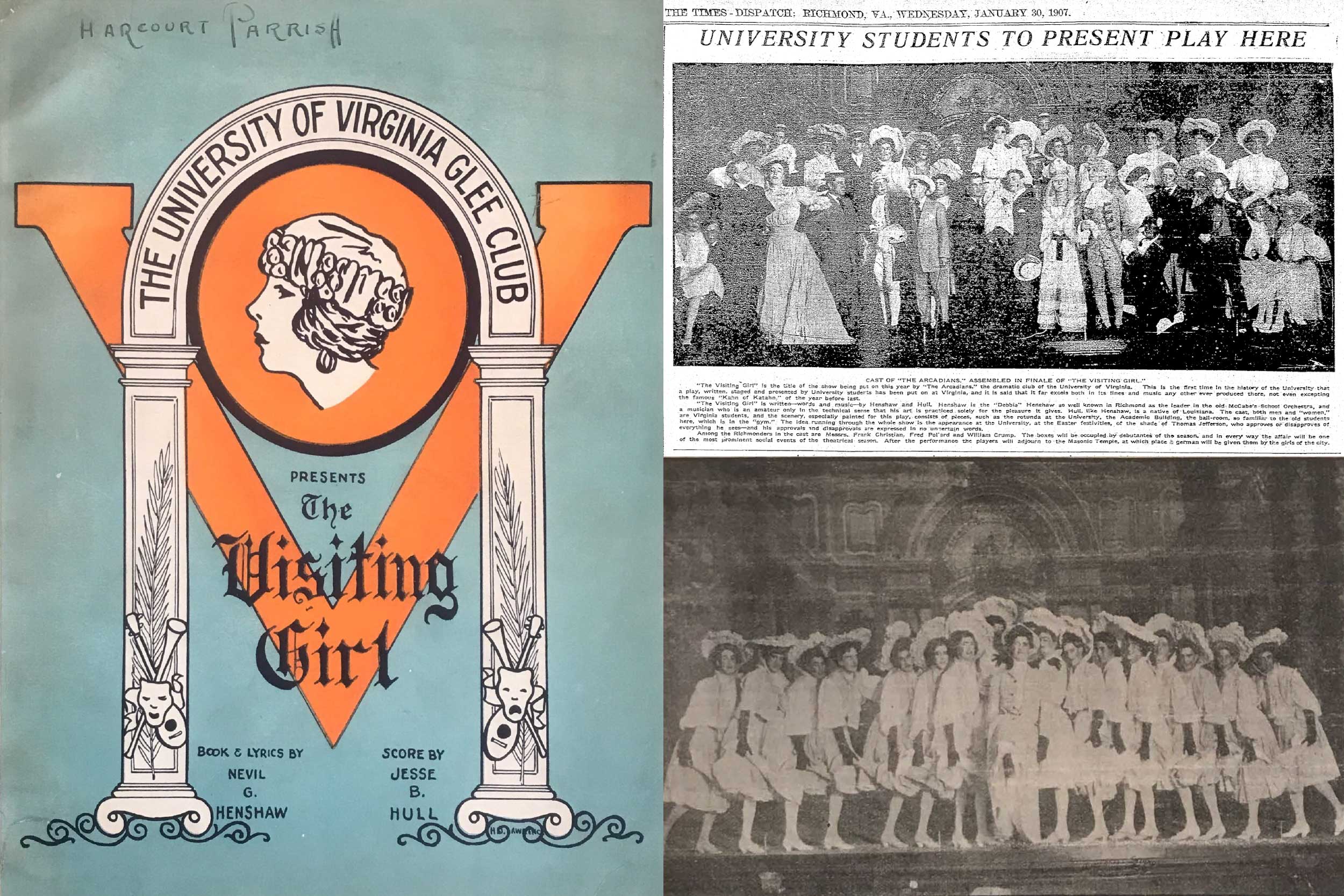

16. https://giving.virginia.edu/lawnandrange/lawn-directory/ Henshaw, N. G.

17. Nevil Gratiot Henshaw The visiting girl, 1907, Accession #8426, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va. Visiting Girl Manuscript, p. 17.

18. Nevil Gratiot Henshaw The visiting girl, 1907, Accession #8426, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va. Visiting Girl Manuscript, p. 22.

19. Nevil Gratiot Henshaw The visiting girl, 1907, Accession #8426, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va. Visiting Girl Manuscript, p. 22.

20. “Arcadians Trip Huge Success,” College Topics, February 13, 1907.

21. Edward N. Main to the Director of UVA Glee Club, 01 March 1936 in Papers of the University Glee Club 1920-1961 Special Collections