According to Barringer, rigid hereditary determinism predetermined the absolute limit of African Americans’ biological and social advancement. He argued that with emancipation came reversion of African Americans to “savage” status, creating a new, degenerate black generation that could not possibly survive in contact with civilized white society.

Barringer believed that under the conditions of slavery, blacks had advanced beyond their natural selection through selective breeding by slave owners. With emancipation came reversion of African Americans to their original “savage nature,” which put them on a path toward extinction, accelerated by an irrational procreation which further exacerbated their genetic inferiority and susceptibility to disease and criminality.4

The drastically high incidence of tuberculosis, syphilis and typhoid fever among African Americans (locally and in cities around the country) indicated nothing to Barringer about overcrowded housing or lack of clean water, sanitation or safe meats and pasteurized milk. Instead the high morbidity and mortality rates of African Americans proved the genetic unfitness of a “markedly criminal race.” Without white intervention, Barringer condemned blacks to a life of barbarism and death. To Barringer, the “Negro Problem” was more than a political problem; it was a huge public health threat to whites.

Barringer’s tripartite solution to the “Negro Problem” was political disfranchisement, transferring responsibility for African American education from black to white teachers, and training blacks to be law-abiding laborers and artisans. As he wrote, “Every Negro doctor, lawyer, teacher or other leader in excess of the immediate needs of his own people is an antisocial produce, a social menace.”5

Eugenics flourished under the leadership of President Edwin Alderman (1903-27) as he set out to build the research base of the University with recruitment of leading men of eugenic science into schools across Grounds: These included Harvey Jordan, Robert Bean and Lawrence Royster in the medical school; George Ferguson in education; Orlando White as director of UVA’s biological station; and Ivey Lewis as chair of biology.

Together these faculty created eugenics research and education programs at UVA and throughout the state, and in doing so, trained UVA students as well as high school and college teachers in eugenic racism. They also collaborated with nationally renowned eugenics investigators, and presented their work at international eugenics meetings. Fully immersed in race science, these men contributed directly and indirectly to ethically contemptuous laws and policies designed to maintain a culture of white supremacy, and exclusionary white privilege.

Jordan, a professor of embryology, genetics and histology, was one of Alderman’s early recruits. Joining the faculty in 1907, he served as dean of the medical school from 1939 to 1949. Believing that blacks inherited a susceptibility to contracting diseases such as syphilis and tuberculosis, Jordan called for compulsory registration of all who were ill. He argued that proposed eugenic marriage, segregation and sterilization laws, were public and racial health measures that “should form part of the health code, to be administered under the State Police powers.”6 The promise of eugenics as a solution to society’s ills, and the power of physicians in solving such problems was best summed up when Jordan declared at the 1st International Congress of Eugenics in 1912 that “the future physician must also take a more active part in helping to shape legislation in the interest of race welfare.”7

Chair of Anatomy Dr. Robert Bean argued that the physical features of African Americans confirmed their inferiority when compared to whites. Furthermore, he advanced “human types that represent different degrees of susceptibility of disease may be segregated and given differential treatment.”8 Through medical school core courses, Jordan and Bean, combined, taught about 20% of the medical school curriculum.

Along similar lines, George Oscar Ferguson, a professor in the education school, in his use of intelligence testing among blacks, mixed-race and white children concluded, “It does not seem possible to raise the scholastic attainment of the Negro to an equality with that of the white. … [N]o expenditure of time or money would accomplish this end, since education cannot create mental power, but can only develop that which is innate.”9

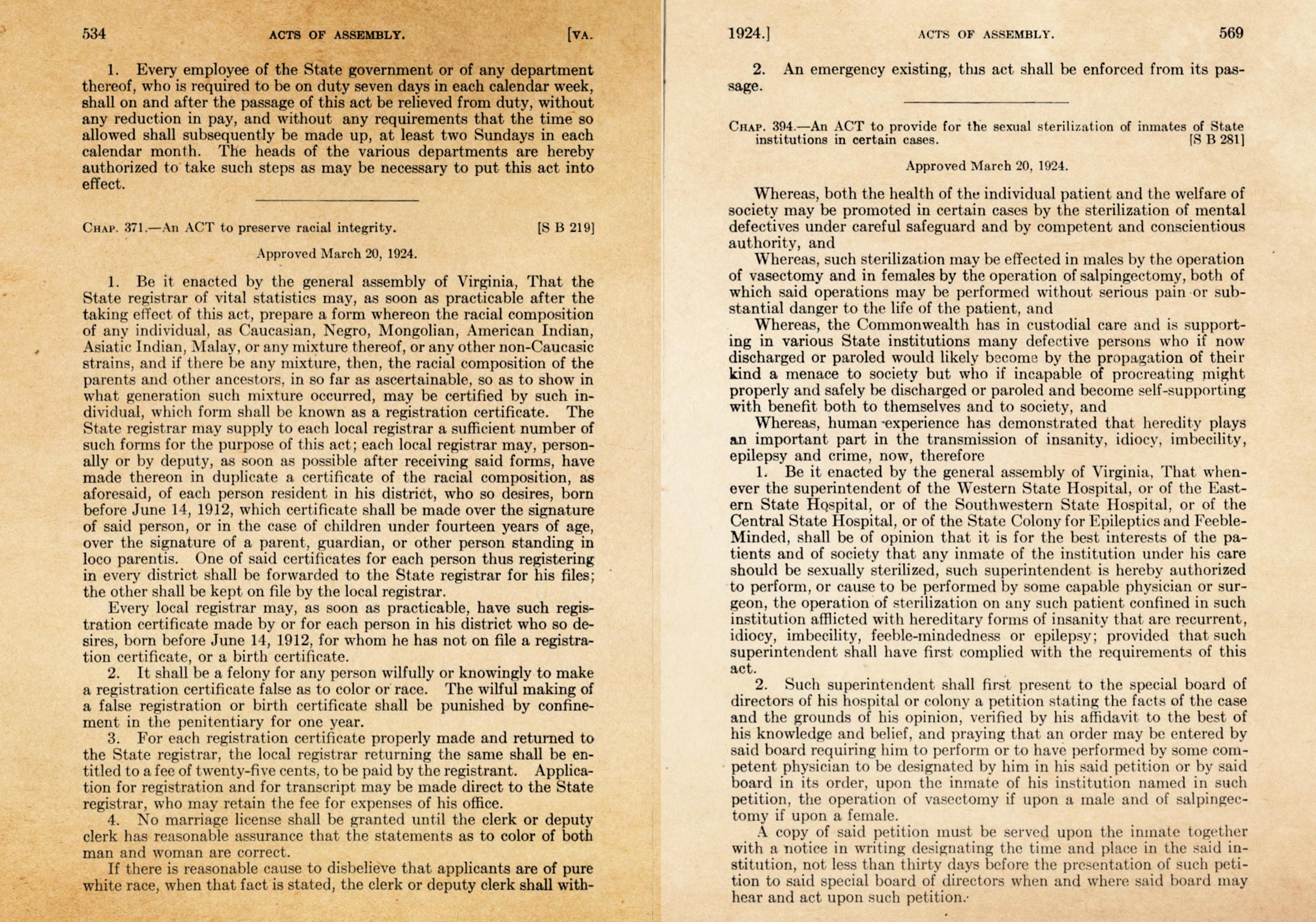

Eugenics began to shape public policy nationally as early as 1907, when Indiana passed a sterilization law. Two Virginia eugenics laws, both passed in 1924, had a profound impact in the commonwealth and throughout the country. The Virginia Sterilization Act and the Racial Integrity Act not only legalized sterilization of the mentally ill and persons of low literacy, but also cemented discrimination against marginalized and vulnerable populations, including African Americans. These laws codified Jim Crow into every aspect of community life, and in doing so, denied African Americans access to medical care, jobs and fair wages, as well as higher education and professional training. Simply put, eugenic laws created the “one drop rule,” where one drop of African American blood restricted a person of color to life behind the veil.10

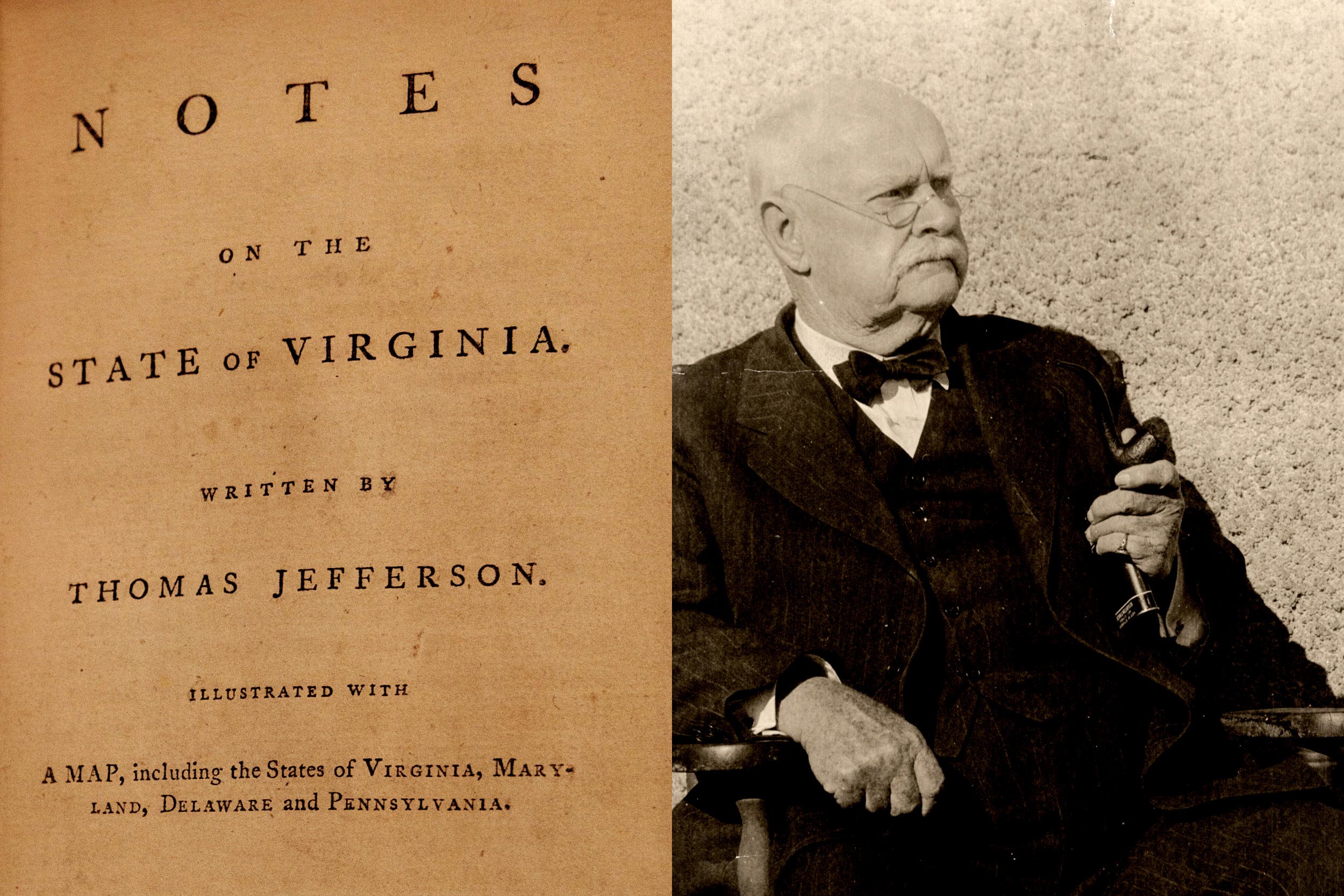

![Jefferson is credited with the language, “all men are created equal,” but also argued “any attempt to assimilate [Blacks] with the American polity is a greater threat to the integrity of the republic than naturalizing immigrants.” (Photo by Sanjay Suchak, Title page of 'Notes on the State of Virginia' by Thomas Jefferson](/sites/default/files/notes_on_the_state_of_virginia_ss_inline.jpg)