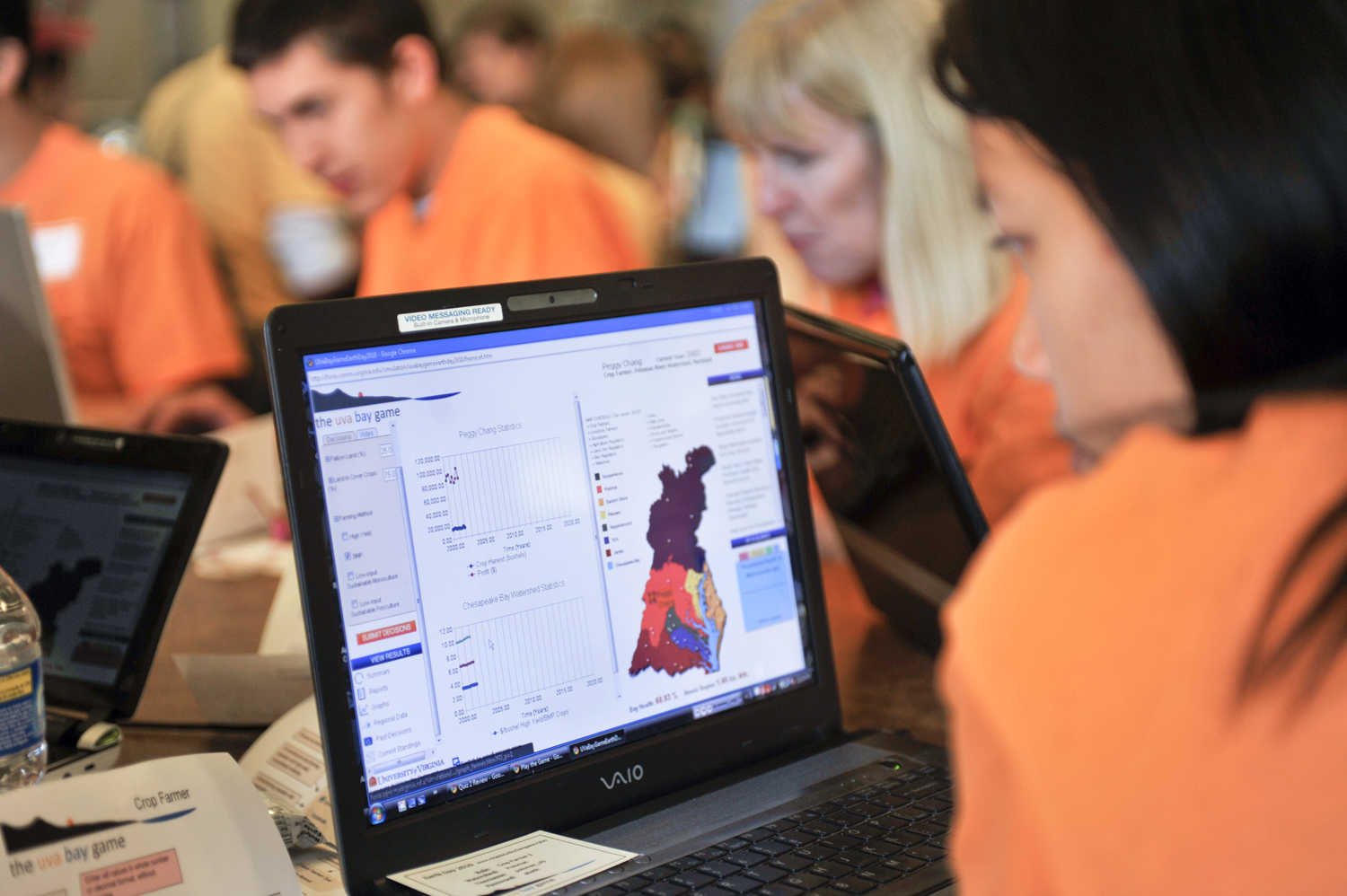

April 9, 2010 — More than 100 University of Virginia students, faculty members and guests showcased the U.Va. Bay Game on Thursday at Clark Hall. The interactive computer game simulates conditions on the Chesapeake Bay and its watershed, and how human decisions affect the health of the bay.

Hosting the event were Thomas C. Skalak, U.Va. vice president for research; Philippe Cousteau, co-founder of the environmental education organization Azure Worldwide; and Dave Smith, environmental sciences professor.

The Bay Game, conceived and developed at U.Va., allows players to take on the roles of Chesapeake Bay stakeholders, including farmers, watermen, developers and policymakers. Each player's decisions affect the outcome for every other player or stakeholder, and, ultimately, the health of the bay.

Participants at the event included real farmers, watermen, developers and policymakers. Guests included Jeff Lape, director of the EPA's Chesapeake Bay Program; Ann Jennings, Virginia executive director of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation; and Joe Jasinski, distinguished engineer at IBM's A Smarter Planet.

The Chesapeake Bay Game is a tool to help demonstrate the importance of political and civic collaboration in conservation efforts. The goal is to find a balance between creating the conditions needed for a healthy environment and maintaining strong economies.

"The Bay Game shows how human behavior is interrelated, how what we do in one location affects people and the environment here and everywhere," Skalak said. "It is our goal with this tool to inform public policies, private investment trends and societal behaviors in ways that will enhance human health, economic prosperity and environmental sustainability."

Cousteau, the grandson of famed ocean explorer and conservationist Jacques Yves Cousteau, said that the complex environmental, political and social issues facing the Chesapeake Bay require a creative approach to problem-solving, and that collaboration is the key.

"Through the Bay Game, U.Va. has created a pioneering tool that considers both environmental impact and the well-being of real people and communities. This project gives people the knowledge to make a positive difference," he said.

Extending over six states and the District of Columbia and covering 64,000 square miles, the Chesapeake Bay watershed is the largest estuary in the United States. It is affected daily by a broad range of individuals, communities and industries within its boundaries, many with conflicting interests.

"What we need is a new way of thinking about environmental problems," said Lape, the EPA's Chesapeake Bay Program director. "The Bay Game is a progressive tool that brings together the power of the local – the realization that we're all in this together.

"We have enormous problems to solve," he told the student players, "and you are the generation this is being passed on to."

Smith originally conceived the idea of an interactive computer simulation game for a course he teaches on the Chesapeake and its extensive multistate watershed.

"My goal is to try to create environmentally literate people who can go out – whether they become attorneys or practicing scientists, or general citizens – and be able to make informed decisions when it comes to scientifically complex areas, and one of those areas is the Chesapeake Bay," he said.

Players of the Bay Game, representing the 16.7 million residents in the watershed, make decisions based on an assigned stakeholder role. Farmers, for example, decide whether to leave land fallow or apply cover crops; land developers decide between regular and sustainable development; crabbers decide methods of harvesting and length of season.

The game provides a scientifically sound and true-to-life method to illustrate what will happen if people take collaborative action and the consequences if they don't.

"We're trying to help students see how the things people do – whether farmers, or a policymaker, a developer or a waterman, impact not only a natural system like the Bay, but also every other stakeholder in the watershed," Smith said.

He realized while teaching his courses that he needed a tool to help students understand how a highly complex natural system works, and, particularly, how human decisions and activities affect the health of that resource.

"I want my students to make a difference and this is a tool that will allow them to better understand and be a little more reflective and pensive on important issues that will affect them, and their children and grandchildren."

One such student is Avery Paxton, a third-year environmental sciences major in the College of Arts & Sciences who played the game previously and Thursday and has taken Smith's Chesapeake Bay class. She has a particular interest in the bay and its watersheds; she grew up visiting her grandparents in Onancock, on Virginia's Eastern Shore.

"The game gives you a good sense of how necessary it is for everyone in the different roles and regions to cooperate on land management and conservation," she said. "You get a more profound appreciation of the effects of your actions on others and on the Bay's health. It broadens your view beyond just your self interest in a particular role."

Sponsored by the Office of the Vice President for Research, the game was created with the input and knowledge of 11 departments in eight of the University's academic units, including: the School of Engineering and Applied Science, McIntire School of Commerce, Department of Environmental Sciences in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, School of Architecture, School of Law, Darden School of Business, Curry School of Education and the School of Medicine.

Each team contributed expertise and data, including real statistics on variables such as crab population and pollution. Jeffrey Plank, associate vice president for research, helped pull the teams together and coordinated development over a period of more than a year. Gerard Learmonth, research associate professor of systems and information engineering, serves as the lead designer.

Azure Worldwide, a strategic development company that focuses on environmentally sustainable design, took interest in the project last spring after co-founder Andrew Snowhite, a U.Va. environmental sciences alumnus ('97), learned of U.Va.'s many sustainability efforts. He contacted President John T. Casteen III's office and was put in touch with the Bay Game's developers. By September, U.Va. and Azure Worldwide were partners. The team hopes to eventually develop K-12 versions of the game, and perhaps versions for other watersheds in the U.S. and around the world.

— By Fariss Samarrai

Facts About the U.Va. Bay Game

The game is a large-scale simulation (sim/game) that combines elements of a highly integrated model of the Chesapeake Bay watershed using systems dynamics modeling techniques and an interactive game interface.

The Chesapeake Bay watershed is represented as a collection of seven smaller watershed regions and the bay itself, divided into a north and a south region. The seven watersheds are the Susquehanna River, Patuxent River, Eastern Shore, Potomac River, Rappahannock River, York River and James River.

Players represent farmers, developers, watermen, policymakers and the general public in each regional watershed and the northern and southern portions of the overall bay watershed.

Approximately 64,000 farms throughout the Chesapeake Bay watershed are represented, with players making decisions regarding both crop and livestock farming practices.

The land development sector in each of the watershed regions is represented by the number of urban/residential acres and acres that may be converted from agriculture or forest to development. Land development players engage in making decisions to buy and sell land, as well as choices to develop property they own using conventional practices or sustainable practices.

Players representing watermen make decisions regarding crab fishing related to the method of harvesting (dredging or potting) and the length of the harvesting season. They also have the opportunity to invest in new equipment that would increase their efficiency weighed against the required cash investment.

Player roles also include those of policymakers, who make decisions on land use, the crab industry and agricultural policy. These players incentivize or curtail the other players' decision-making through the choices they make in their respective areas of authority.

In each region, all players also represent members of the public and enter their feelings about the economy, the environment and their perceived quality of life in the region.

The game template is flexible regarding the period of time over which results are projected. Currently, the game projects possible outcomes over a 20-year period.

Hosting the event were Thomas C. Skalak, U.Va. vice president for research; Philippe Cousteau, co-founder of the environmental education organization Azure Worldwide; and Dave Smith, environmental sciences professor.

The Bay Game, conceived and developed at U.Va., allows players to take on the roles of Chesapeake Bay stakeholders, including farmers, watermen, developers and policymakers. Each player's decisions affect the outcome for every other player or stakeholder, and, ultimately, the health of the bay.

Participants at the event included real farmers, watermen, developers and policymakers. Guests included Jeff Lape, director of the EPA's Chesapeake Bay Program; Ann Jennings, Virginia executive director of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation; and Joe Jasinski, distinguished engineer at IBM's A Smarter Planet.

The Chesapeake Bay Game is a tool to help demonstrate the importance of political and civic collaboration in conservation efforts. The goal is to find a balance between creating the conditions needed for a healthy environment and maintaining strong economies.

"The Bay Game shows how human behavior is interrelated, how what we do in one location affects people and the environment here and everywhere," Skalak said. "It is our goal with this tool to inform public policies, private investment trends and societal behaviors in ways that will enhance human health, economic prosperity and environmental sustainability."

Cousteau, the grandson of famed ocean explorer and conservationist Jacques Yves Cousteau, said that the complex environmental, political and social issues facing the Chesapeake Bay require a creative approach to problem-solving, and that collaboration is the key.

"Through the Bay Game, U.Va. has created a pioneering tool that considers both environmental impact and the well-being of real people and communities. This project gives people the knowledge to make a positive difference," he said.

Extending over six states and the District of Columbia and covering 64,000 square miles, the Chesapeake Bay watershed is the largest estuary in the United States. It is affected daily by a broad range of individuals, communities and industries within its boundaries, many with conflicting interests.

"What we need is a new way of thinking about environmental problems," said Lape, the EPA's Chesapeake Bay Program director. "The Bay Game is a progressive tool that brings together the power of the local – the realization that we're all in this together.

"We have enormous problems to solve," he told the student players, "and you are the generation this is being passed on to."

Smith originally conceived the idea of an interactive computer simulation game for a course he teaches on the Chesapeake and its extensive multistate watershed.

"My goal is to try to create environmentally literate people who can go out – whether they become attorneys or practicing scientists, or general citizens – and be able to make informed decisions when it comes to scientifically complex areas, and one of those areas is the Chesapeake Bay," he said.

Players of the Bay Game, representing the 16.7 million residents in the watershed, make decisions based on an assigned stakeholder role. Farmers, for example, decide whether to leave land fallow or apply cover crops; land developers decide between regular and sustainable development; crabbers decide methods of harvesting and length of season.

The game provides a scientifically sound and true-to-life method to illustrate what will happen if people take collaborative action and the consequences if they don't.

"We're trying to help students see how the things people do – whether farmers, or a policymaker, a developer or a waterman, impact not only a natural system like the Bay, but also every other stakeholder in the watershed," Smith said.

He realized while teaching his courses that he needed a tool to help students understand how a highly complex natural system works, and, particularly, how human decisions and activities affect the health of that resource.

"I want my students to make a difference and this is a tool that will allow them to better understand and be a little more reflective and pensive on important issues that will affect them, and their children and grandchildren."

One such student is Avery Paxton, a third-year environmental sciences major in the College of Arts & Sciences who played the game previously and Thursday and has taken Smith's Chesapeake Bay class. She has a particular interest in the bay and its watersheds; she grew up visiting her grandparents in Onancock, on Virginia's Eastern Shore.

"The game gives you a good sense of how necessary it is for everyone in the different roles and regions to cooperate on land management and conservation," she said. "You get a more profound appreciation of the effects of your actions on others and on the Bay's health. It broadens your view beyond just your self interest in a particular role."

Sponsored by the Office of the Vice President for Research, the game was created with the input and knowledge of 11 departments in eight of the University's academic units, including: the School of Engineering and Applied Science, McIntire School of Commerce, Department of Environmental Sciences in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, School of Architecture, School of Law, Darden School of Business, Curry School of Education and the School of Medicine.

Each team contributed expertise and data, including real statistics on variables such as crab population and pollution. Jeffrey Plank, associate vice president for research, helped pull the teams together and coordinated development over a period of more than a year. Gerard Learmonth, research associate professor of systems and information engineering, serves as the lead designer.

Azure Worldwide, a strategic development company that focuses on environmentally sustainable design, took interest in the project last spring after co-founder Andrew Snowhite, a U.Va. environmental sciences alumnus ('97), learned of U.Va.'s many sustainability efforts. He contacted President John T. Casteen III's office and was put in touch with the Bay Game's developers. By September, U.Va. and Azure Worldwide were partners. The team hopes to eventually develop K-12 versions of the game, and perhaps versions for other watersheds in the U.S. and around the world.

— By Fariss Samarrai

Facts About the U.Va. Bay Game

The game is a large-scale simulation (sim/game) that combines elements of a highly integrated model of the Chesapeake Bay watershed using systems dynamics modeling techniques and an interactive game interface.

The Chesapeake Bay watershed is represented as a collection of seven smaller watershed regions and the bay itself, divided into a north and a south region. The seven watersheds are the Susquehanna River, Patuxent River, Eastern Shore, Potomac River, Rappahannock River, York River and James River.

Players represent farmers, developers, watermen, policymakers and the general public in each regional watershed and the northern and southern portions of the overall bay watershed.

Approximately 64,000 farms throughout the Chesapeake Bay watershed are represented, with players making decisions regarding both crop and livestock farming practices.

The land development sector in each of the watershed regions is represented by the number of urban/residential acres and acres that may be converted from agriculture or forest to development. Land development players engage in making decisions to buy and sell land, as well as choices to develop property they own using conventional practices or sustainable practices.

Players representing watermen make decisions regarding crab fishing related to the method of harvesting (dredging or potting) and the length of the harvesting season. They also have the opportunity to invest in new equipment that would increase their efficiency weighed against the required cash investment.

Player roles also include those of policymakers, who make decisions on land use, the crab industry and agricultural policy. These players incentivize or curtail the other players' decision-making through the choices they make in their respective areas of authority.

In each region, all players also represent members of the public and enter their feelings about the economy, the environment and their perceived quality of life in the region.

The game template is flexible regarding the period of time over which results are projected. Currently, the game projects possible outcomes over a 20-year period.

— By Fariss Samarrai

Media Contact

Article Information

April 8, 2010

/content/uva-azure-worldwide-showcase-uva-bay-game