Luanne McKinnon, who earned her Ph.D. in art history from the University of Virginia in May, is a renowned art scholar and curator, poised to turn her dissertation on Picasso into a book. At 60, she is also one of the longest-living survivors of cystic fibrosis, a genetic pulmonary condition with a current average life span of 37 years.

In the winter of 1969-70, McKinnon was diagnosed at age 14 and given five years to live. Five years later, defying her doctors’ expectations, 19-year-old McKinnon was studying abroad in Europe, hauling her nebulizer (a microwave-sized machine used to administer aerosolized medication) between countries the way other students haul overloaded backpacks.

“I was going to school in Rome. I was not dead. I was excited, I was happy. I dragged my life-saving nebulizer to Amsterdam, or Paris, or Venice, or Athens,” McKinnon said. “This is what I have been given. It was a pretty heavy suitcase to haul around, but I felt that I was strong enough.”

Forty years later, her determination in carting her nebulizer among Europe’s greatest sights reflects a philosophy that has defined her career and her life: choosing to seek life’s beauty even while facing its often threatening realities. For McKinnon, that meant building a life around the visual arts.

“I think that there is a relationship between trauma and the desire for beauty,” she said. “The uniqueness of creative humans just seemed to be what I needed to think about, what I needed to look at and to understand.”

“Despite all my misgivings about this torturous world – ongoing wars, disparity in classes, increasing poverty – I love this life and I always have. I have always been so curious about so many things. And I am so very fortunate to remain here, for now.” - Luanne McKinnon

After earning a Master of Fine Arts degree in painting from Texas Christian University, McKinnon joined a private art dealership in Fort Worth, gaining entrée into the national and international art market of the early 1980s, where she mingled with prominent art dealers and contemporary artists like Cy Twombly and Robert Rauschenberg. Eventually, she opened her own private art dealing, McKinnon Modern, in New York, buying and selling post-World War II sculpture, paintings and drawings, including works by Brancusi, Cézanne, Warhol and Twombly.

She enjoyed the work until another war – the Persian Gulf War of the early 1990s – intruded. Watching television coverage in her New York apartment and anticipating the suffering the war would bring, McKinnon realized that she needed to move away from seeing art as a commodity.

“I decided, right then, that I needed to return to the world of thought,” she said. “I wanted to be involved in what art history can do, which is opening our minds and our hearts to the true nature of the variances of creative genius that define the human spirit.”

In 1990, McKinnon moved to Rapidan, near Charlottesville, to begin pursuing graduate work in art history. One of her first professors, Paul Barolsky, connected her to the late Lydia Gasman, a UVA professor and renowned Pablo Picasso scholar. Gasman greeted McKinnon at her apartment on Main Street near the Downtown Mall with a pink turban on her head and a long cigarette in her hand – the beginning of a fortuitous partnership.

“She was eccentric, impassioned and brilliant, and helped launch the beginnings of my dream that I could return [to academia], at the age that I did,” McKinnon said. “Lydia was very demanding, very insistent upon looking deeply at the material produced by Picasso and the surrounding, if not hidden, meanings of the works. I was hooked on this ‘new language’ and worked to perfect my understanding of it, to the best of my ability.”

Grueling hospital stays continually interrupted McKinnon’s studies, as the symptoms of cystic fibrosis periodically worsened. Each time, she checked into the UVA Medical Center and slowly worked her way back to health.

“I enjoyed great care from the great people at UVA’s hospital, and it deepened my ties to the place,” McKinnon said. “They were always, somehow, saving my life.”

Colleagues in the art history department substituted in McKinnon’s classes, while others, including Barolsky, zipped into hazmat suits to visit her in her fragile state.

“Her friends came from everywhere to help her, from all of the places to which they had scattered,” said former professor David Summers, who became McKinnon’s adviser after Gasman’s retirement. “I actually have never seen anything like it. She makes people feel that she ought to be alive, ought to be able to do what she needs and wants to do.”

During one of her hospital stays, Summers wrote McKinnon a card remarking, “You must love this life so much, to want to stay here so badly.”

“I thought it was such a wise thing to say, because it really did hit the nail on the head. I have fire in the belly, as they say,” McKinnon said. “Despite all my misgivings about this torturous world – ongoing wars, disparity in classes, increasing poverty – I love this life and I always have. I have always been so curious about so many things. And I am so very fortunate to remain here, for now.”

In 2000, McKinnon’s studies were interrupted for a happier reason. Summers was away for the semester at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and McKinnon shared his office with Daniel Reeves, whose work was being featured in the Virginia Film Festival. The officemates fell in love and were married in 2001 in Scotland, where Reeves was a senior research fellow in Edinburgh.

“We met because of this shared UVA real estate, and of course, destiny!” she said.

After McKinnon completed coursework requirements for her Ph.D., the couple moved to Scotland and France, where McKinnon – her reputation as Gasman’s protégée preceding her – gave talks on Picasso’s work and continued researching her dissertation on Picasso’s “Guernica,” an anti-war masterpiece depicting the bombing of a Spanish village.

McKinnon, at the Gernika Peace Museum in Spain, stands in front of a duplicated image of Picasso’s “Guernica” showing a timeline of its exhibition history in Europe and the U.S. The museum is near the site of the Luftwaffe bombing that inspired Picasso’s

Upon returning to the U.S., McKinnon set aside her dissertation to direct the Cornell Fine Arts Museum at Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, and later, the University of New Mexico Art Museum in Albuquerque, which she led until her health took a more dramatic downturn in 2010

As McKinnon fought for her life, doctors at Stanford University Hospital in Palo Alto, California placed her on the waiting list for a double-lung transplant, which, though it cannot cure cystic fibrosis, can significantly improve patients’ quality of life.

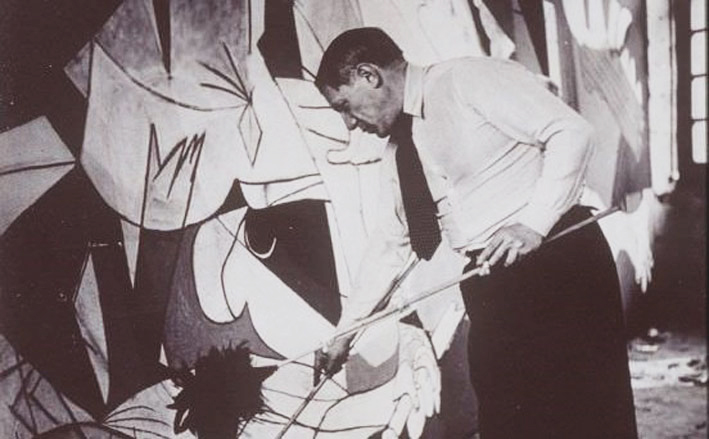

Picasso painting “Guernica” in Paris in May of 1937. (Photo by Dora Maar)

Unable to return to work full-time, she turned again to the study of art, reapplying to UVA’s art history program and, within two years, completing her dissertation – a work that Barolsky calls “beautifully written, lucid and out of the ordinary.” Fittingly, it explores a work of art created during a time of war – something tragic transformed into something beautiful.

In May, McKinnon walked the Lawn as a graduate of the University of Virginia, four years after her transplant. It was the culmination of many years of hard work and still more years of defying expectations.

“Walking that land, being back, I had this palpable sense of how extraordinary my experience was there, and I felt so grateful to have gotten through the eye of the needle, to have done the work I had done, and to be alive, thanks in part to the care of those in the pulmonary care unit at UVA,” McKinnon said. “It was emotional, a wonderful sense of sweet gratitude about what the place and its people have given me.”

Media Contact

Article Information

December 7, 2015

/content/uva-phd-graduate-60-among-longest-living-survivors-cystic-fibrosis