Every other Friday, 40 teachers from Charlottesville elementary schools take on the role of student at the University of Virginia to improve their scientific instruction skills that, in turn, will improve their students' preparedness for the Virginia Standards of Learning exams.

The Curry School of Education, and College of Arts & Sciences are partnering with Charlottesville city schools to strengthen science instruction.

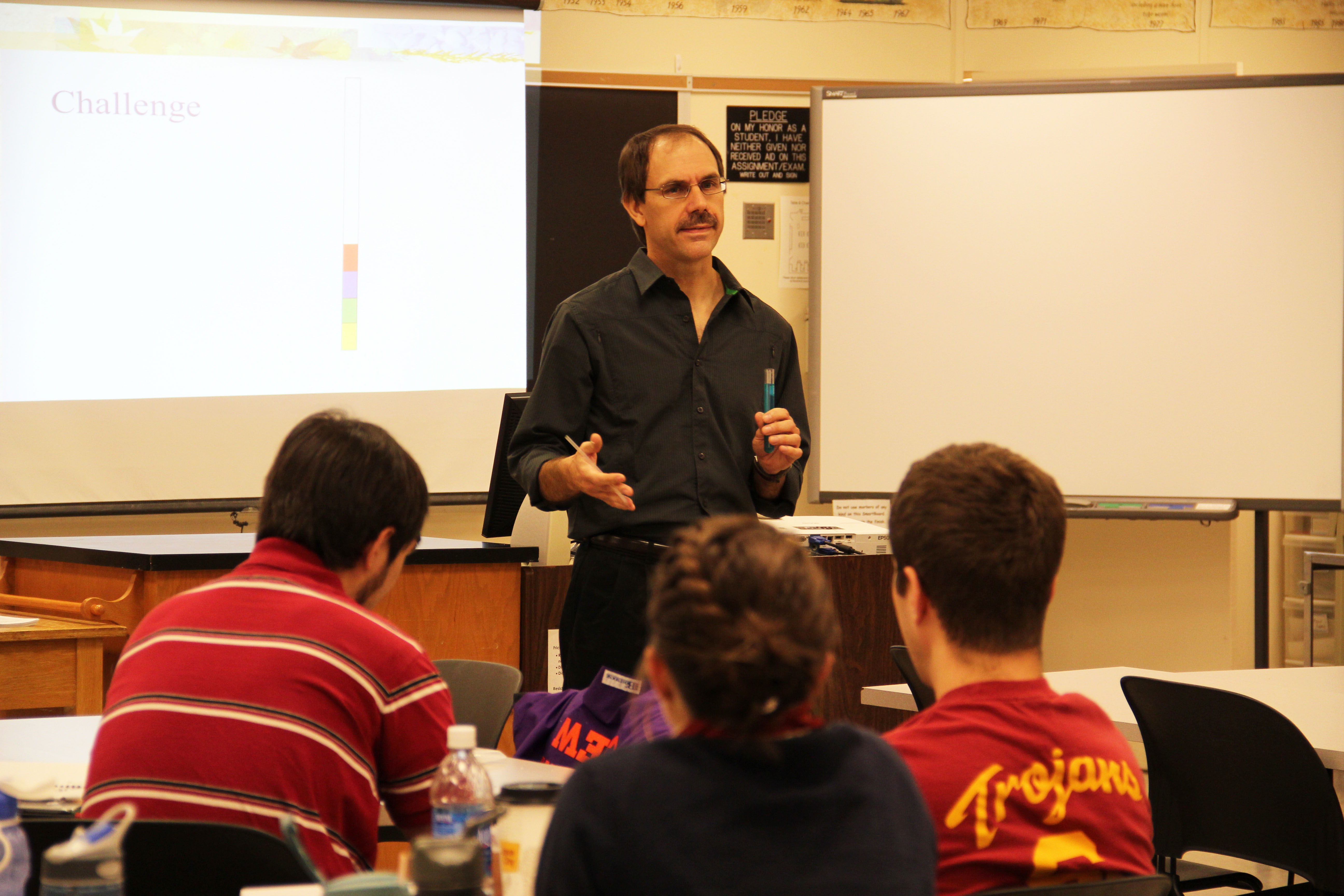

Randy Bell, associate professor of science education in the Curry School, teamed with College associate professor of astronomy Ed Murphy, Curry assistant professor of science education Jennie Chiu, science coordinator for the Charlottesville City Schools Jessica Kalagher and Curry doctoral student Bridget Mulvey to create a six-week professional development program to teach scientific inquiry and the nature of science to local kindergarten through fifth-grade teachers.

The program, headed by Bell, is funded by a $273,000 grant from the Virginia Mathematics and Science partnership, funded by the Virginia Department of Education.

The Mathematics and Science partnership grants were created so that university professors could help improve local public school instruction through teaching pedagogical tactics to the public schools' teachers, according to the Virginia Department of Education's website.

Eric Rhoades, science coordinator of the Virginia Department of Education, emphasized the importance of science education development. "Our country relies on having a science-literate citizenry asking questions about the natural world, investigating and making the lives of people better," he said.

The program began last fall and will continue through fall semester 2012, during which Bell and his colleagues will teach more than 100 Charlottesville teachers during three semesters.

According to Bell, most science pedagogical teaching focuses on developing a deep comprehension and informational base about a particular topic of science, such as physics or chemistry. However, Bell's course focuses on how students learn about science and which scientific teaching strategies are the most effective.

The course also aims to challenge and correct many scientific misconceptions, especially those traditionally misrepresented in textbooks. For example, many have never been taught the real difference between a theory and a law. Most people believe that theories can eventually become laws once they are proven and that scientific laws are absolute. However, this is not true, Bell said, explaining that a theory can never become a law and that even scientific laws can change with new evidence. A better distinction between theories and laws is that laws are descriptive generalizations, whereas scientific theories offer explanations. Both are based on substantial evidence and can change in light of new data. The goal of the program is for elementary teachers to learn how to teach, as well as understand, these topics accurately.

Inquiry is another topic addressed in the course. Bell explained that the course addresses what inquiry instruction is and how to modify "cookbook" lab activities into inquiry-based investigations. "Too often, teachers are given the message that inquiry instruction is complicated and time-intensive. On the other hand, sometimes teachers get the impression that every hands-on activity is an inquiry activity," Bell said. In reality, inquiry instruction can be as simple as observing and inferring, as long as students are analyzing data to answer a research question.

For example, a common earth science activity is to have students cut out photographs of the moon in different phases, mount them on a monthly calendar on the proper date, and label each of the eight major moon phases. For this to be an inquiry activity, the teacher might instead challenge students to figure out the sequence of phases by observing the moon every night for a month and recording their observations. Students might also answer a question about whether the moon rises and sets at the same time every night by viewing a computer simulation of lunar activity for several sequential evenings. The key is that there must be a question and students, not the teacher or a book or website, answer the question by making sense of data.

Area teachers participate in the daylong program every other Friday. The grant provides funds for materials and instruction, as well as funds to pay substitute teachers on the days the full-time teachers are participating in the course. Additionally, teachers receive both re-certification and graduate school credits.

The course goes beyond Bell's classroom, though. The teachers' homework is to teach specific lessons on the nature of science and inquiry in their own classrooms. Each teacher has a video recorder, provided by the grant, which they use to both film their lesson and reflect on it. Then, the instructors bring the recordings back to Bell's class for review and feedback.

So far, the feedback has been positive. According to Bell, teachers are using the techniques and lessons they learn in his class in their own classrooms.

Kelly Bullock, a 1985 Curry alumna, teaches kindergarten at Clark Elementary School. She explained that Bell's class has helped improve her scientific teaching skills.

"I really do believe it's impacted my instruction, and it's made me a better teacher and that way I can be better for my students," she said.

Bullock said that she puts her own spin on Bell's educational activities as she brings the nature of science into her classroom. For example, Bell presented a lesson where the elementary teachers sequentially observed a series of three sets of fossil footprints and used their observations to make inferences about what kinds of animals left the prints and what transpired. Bell then connected the process that the teachers went through to understand the fossil footprints to the work of paleontologists. "Observation and inference are critical to the development of scientific knowledge – scientific methods include more than experiments," Bell said.

In her class, Bullock's students observed parts of a photo of President Obama as a child and his mother in order to practice their observing skills and infer the identity of the child. She then connected students' observing and inferring skills to the work of scientists as they make sense of the natural world. Activities such as these help students learn what science is, how it is done, and inspire them to succeed in future science courses.

Rhoades echoed Bullock's sentiments, saying that Bell has made a real difference in improving science education in Charlottesville. The principles he is teaching in his course really give teachers an effective vision of how students learn science best and how they should be engaging students in a scientific endeavor," he said.

– by Lisa Littman

Media Contact

Article Information

May 1, 2012

/content/uva-professor-helps-charlottesville-teachers-hone-science-teaching-skills