Part I

Jan. 7, 2008 — Among the renowned literary journals of the early 20th century, women editors abound: Harriet Monroe at Poetry, Marianne Moore at The Dial, Margaret Anderson at The Little Review, Dora Marsden at The Egoist.

Yet academic literary journals did not share the forward thinking of their independent cousins. In fact, by the 1950s, among the preeminent university-based literature journals only one could claim a woman editor: The Virginia Quarterly Review.

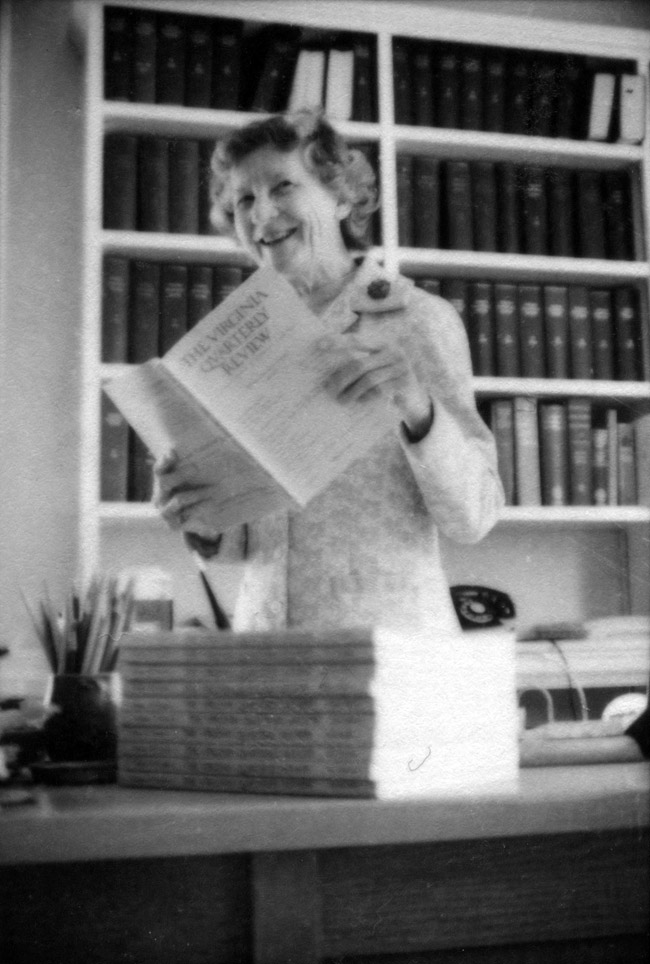

Charlotte Kohler served as the journal’s sixth editor and enjoyed the longest tenure of any editor of the VQR, from 1946 until 1975 (she was managing editor from 1942–1946). A graduate of Vassar, Kohler had studied under VQR founder James Southall Wilson at the University of Virginia, becoming one of its first female Ph.D.s in 1936. Kohler completed her M.A. in 1933 in only nine months and was U.Va.’s first female Phi Beta Kappa in 1936.

As with so many men working at the University during World War II, Kohler’s predecessor, VQR editor Archibald Shepperson, left in 1942 to go to war. Wilson and then-University president John Newcomb wanted to replace Shepperson with a “war-proof” editor, and Wilson thought of Kohler, his former student. Newcomb agreed with Wilson’s choice and insisted that Kohler become editor. Although Shepperson retained the title of editor until 1946, Kohler actually filled both the managing editor and editor positions in his absence.

Considering the hiring inequities faced by women editors at other academic journals, Kohler felt fortunate about being hired at the VQR. Kohler recalled about her hiring, “He [Newcomb] made a point of [hiring me], which I think was very generous on his part when you consider that Miss Helen MacAfee was managing editor of The Yale Review for years untold under Wilbert Cross as editor. Then when he died, she wasn’t made editor. She kept on for the rest of her time as ‘managing editor’ even though she was doing the whole thing. A remarkable lady … and one reason why I appreciated Mr. Newcomb’s actions even more.”

Kohler’s indignation at The Yale Review’s rebuke of MacAfee should be put into an historical context. Kohler likely would not have described herself as a feminist; that term came into vogue in the last third of the twentieth century. But we may call Kohler’s sentiments feminist.

Kohler wrote that the impulse behind her dissertation — The Elizabethan Woman of Letters: The Extent of Her Literary Activities — was to revise lopsided presumptions about women writers in the sixteenth and seventeenth century.

In her dissertation, Kohler took issue with the notion that Elizabethan women writers were scarce:

"This study of the extent of the literary activities of the Elizabethan woman of letters owes its inception to a passage in an essay of Virginia Woolf’s, in which she remarks that 'it is a perennial puzzle why no woman wrote a word of that extraordinary literature when every other man, it seemed, was capable of song or sonnet.'

I hope that this present attempt may serve to dispel any doubts as to the number of women who engaged in penwork in Elizabethan times, no matter how low a rating the quality of their work may still deserve and receive."

Women at work, Kohler believed, deserved the same credit as their male peers, whether they be Elizabethan sonneteers or editors at The Yale Review.

Virginia Roots

Born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1908, Kohler was product of the public school system. “Actually in Richmond in those days you could get a better public school education than a private school education,” Kohler noted. “John Marshall was the only high school in Richmond at that time. So it was a melting pot. It drew everyone. It was very ugly, very crowded, but it had good teachers.”

Kohler was the first in her family to go to college. She recalled that her parents told her, “You can go anywhere you want, but you can’t cross the Mississippi.” Vassar College kept her on this side of the river but as far away from Richmond as possible.

Kohler had the misfortune of graduating just months before Black Friday in 1929. “The Depression made it hard to find work,” she said. Faced with few job prospects, she tried her hand at the latest cottage industry — becoming an expatriate American writer in Europe. “I thought I was going to be the Great American Writer and that would be a good place to do it,” she said. “But you see it takes more to be the Great American Writer than just the wish. It takes a great drive and determination.”

Kohler returned home from Europe one year later with little to show for her time abroad. When she showed her mother her few pages of work, her mother said, “Is that all?” In a 1975 interview, Kohler said little about the quality of her writing, except to say that it was “jejune.” So she did what many liberal arts majors have done before and since: She went to graduate school. “If you can’t get a job, you can’t just sit at home and do nothing except read and be lazy. So I came here [to U.Va.].”

Kohler completed her Ph.D. in 1936, but without teaching experience (at the time, the University did not allow women students to be teaching assistants), she struggled to find work as an English professor.

Kohler applied for a position at nearby Mary Baldwin College in Staunton, Virginia, but was rejected outright because she smoked, enjoyed an occasional drink, and “was not a Presbyterian,” she said. The Women’s College of the University of North Carolina in Greensboro had fewer ecclesiastical prerequisites, and Kohler taught there for two years beginning in 1941.

While her scholarship didn’t yield an immediate job, it did set the stage for one of her most generous gifts in a life full of generous gifts given to writers. In 1948, six years into her tenure as the VQR editor, Kohler’s lifelong interest in Elizabethan women writers took her to a Waukegan, Illinois, bookseller. There she found and purchased an original edition of Mary Wroth’s Urania, a seventeenth-century pastoral romance.

In 1989, Jo Roberts, a professor of English at Louisiana State University, was researching Wroth’s work for an upcoming book. Kohler agreed to let Roberts see her copy of Urania. “Imagine my surprise,” Roberts wrote, “as I turned over the leaves and saw Wroth’s own distinctive italic handwriting in the margins!" Five years later, Kohler mailed the book to Roberts with the inscription, “For Josephine Roberts, with love and gratitude, Charlotte Kohler.” A friend of Roberts told the Pennsylvania Gazette that “Kohler had clearly recognized that Jo was the volume’s ideal possessor, and then had the generosity to act on her recognition.”

Roberts, like Kohler, was a native of Richmond. Perhaps, in Roberts, who was 40 years her junior, Kohler saw a younger version of herself. When Roberts published her study of Wroth’s work in 1995, a year before her death in a car accident, the book was simply dedicated, “For Charlotte.” Roberts was only one of many writers touched by Kohler’s largesse.

— Written by Tim Arnold

Next Tuesday: Part II, Kohler takes the helm of the Virginia Quarterly Review

Jan. 7, 2008 — Among the renowned literary journals of the early 20th century, women editors abound: Harriet Monroe at Poetry, Marianne Moore at The Dial, Margaret Anderson at The Little Review, Dora Marsden at The Egoist.

Yet academic literary journals did not share the forward thinking of their independent cousins. In fact, by the 1950s, among the preeminent university-based literature journals only one could claim a woman editor: The Virginia Quarterly Review.

Charlotte Kohler served as the journal’s sixth editor and enjoyed the longest tenure of any editor of the VQR, from 1946 until 1975 (she was managing editor from 1942–1946). A graduate of Vassar, Kohler had studied under VQR founder James Southall Wilson at the University of Virginia, becoming one of its first female Ph.D.s in 1936. Kohler completed her M.A. in 1933 in only nine months and was U.Va.’s first female Phi Beta Kappa in 1936.

As with so many men working at the University during World War II, Kohler’s predecessor, VQR editor Archibald Shepperson, left in 1942 to go to war. Wilson and then-University president John Newcomb wanted to replace Shepperson with a “war-proof” editor, and Wilson thought of Kohler, his former student. Newcomb agreed with Wilson’s choice and insisted that Kohler become editor. Although Shepperson retained the title of editor until 1946, Kohler actually filled both the managing editor and editor positions in his absence.

Considering the hiring inequities faced by women editors at other academic journals, Kohler felt fortunate about being hired at the VQR. Kohler recalled about her hiring, “He [Newcomb] made a point of [hiring me], which I think was very generous on his part when you consider that Miss Helen MacAfee was managing editor of The Yale Review for years untold under Wilbert Cross as editor. Then when he died, she wasn’t made editor. She kept on for the rest of her time as ‘managing editor’ even though she was doing the whole thing. A remarkable lady … and one reason why I appreciated Mr. Newcomb’s actions even more.”

Kohler’s indignation at The Yale Review’s rebuke of MacAfee should be put into an historical context. Kohler likely would not have described herself as a feminist; that term came into vogue in the last third of the twentieth century. But we may call Kohler’s sentiments feminist.

Kohler wrote that the impulse behind her dissertation — The Elizabethan Woman of Letters: The Extent of Her Literary Activities — was to revise lopsided presumptions about women writers in the sixteenth and seventeenth century.

In her dissertation, Kohler took issue with the notion that Elizabethan women writers were scarce:

"This study of the extent of the literary activities of the Elizabethan woman of letters owes its inception to a passage in an essay of Virginia Woolf’s, in which she remarks that 'it is a perennial puzzle why no woman wrote a word of that extraordinary literature when every other man, it seemed, was capable of song or sonnet.'

I hope that this present attempt may serve to dispel any doubts as to the number of women who engaged in penwork in Elizabethan times, no matter how low a rating the quality of their work may still deserve and receive."

Women at work, Kohler believed, deserved the same credit as their male peers, whether they be Elizabethan sonneteers or editors at The Yale Review.

Virginia Roots

Born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1908, Kohler was product of the public school system. “Actually in Richmond in those days you could get a better public school education than a private school education,” Kohler noted. “John Marshall was the only high school in Richmond at that time. So it was a melting pot. It drew everyone. It was very ugly, very crowded, but it had good teachers.”

Kohler was the first in her family to go to college. She recalled that her parents told her, “You can go anywhere you want, but you can’t cross the Mississippi.” Vassar College kept her on this side of the river but as far away from Richmond as possible.

Kohler had the misfortune of graduating just months before Black Friday in 1929. “The Depression made it hard to find work,” she said. Faced with few job prospects, she tried her hand at the latest cottage industry — becoming an expatriate American writer in Europe. “I thought I was going to be the Great American Writer and that would be a good place to do it,” she said. “But you see it takes more to be the Great American Writer than just the wish. It takes a great drive and determination.”

Kohler returned home from Europe one year later with little to show for her time abroad. When she showed her mother her few pages of work, her mother said, “Is that all?” In a 1975 interview, Kohler said little about the quality of her writing, except to say that it was “jejune.” So she did what many liberal arts majors have done before and since: She went to graduate school. “If you can’t get a job, you can’t just sit at home and do nothing except read and be lazy. So I came here [to U.Va.].”

Kohler completed her Ph.D. in 1936, but without teaching experience (at the time, the University did not allow women students to be teaching assistants), she struggled to find work as an English professor.

Kohler applied for a position at nearby Mary Baldwin College in Staunton, Virginia, but was rejected outright because she smoked, enjoyed an occasional drink, and “was not a Presbyterian,” she said. The Women’s College of the University of North Carolina in Greensboro had fewer ecclesiastical prerequisites, and Kohler taught there for two years beginning in 1941.

While her scholarship didn’t yield an immediate job, it did set the stage for one of her most generous gifts in a life full of generous gifts given to writers. In 1948, six years into her tenure as the VQR editor, Kohler’s lifelong interest in Elizabethan women writers took her to a Waukegan, Illinois, bookseller. There she found and purchased an original edition of Mary Wroth’s Urania, a seventeenth-century pastoral romance.

In 1989, Jo Roberts, a professor of English at Louisiana State University, was researching Wroth’s work for an upcoming book. Kohler agreed to let Roberts see her copy of Urania. “Imagine my surprise,” Roberts wrote, “as I turned over the leaves and saw Wroth’s own distinctive italic handwriting in the margins!" Five years later, Kohler mailed the book to Roberts with the inscription, “For Josephine Roberts, with love and gratitude, Charlotte Kohler.” A friend of Roberts told the Pennsylvania Gazette that “Kohler had clearly recognized that Jo was the volume’s ideal possessor, and then had the generosity to act on her recognition.”

Roberts, like Kohler, was a native of Richmond. Perhaps, in Roberts, who was 40 years her junior, Kohler saw a younger version of herself. When Roberts published her study of Wroth’s work in 1995, a year before her death in a car accident, the book was simply dedicated, “For Charlotte.” Roberts was only one of many writers touched by Kohler’s largesse.

— Written by Tim Arnold

Next Tuesday: Part II, Kohler takes the helm of the Virginia Quarterly Review

Media Contact

Article Information

January 7, 2008

/content/uva-profiles-features-charlotte-kohler-discerning-editor-uncommon-generosity-0