Since the news broke of Wednesday’s shocking assassination of Haiti’s president, Jovenel Moïse, University of Virginia scholars who focus on Haiti have been busy answering media questions about the troubled Caribbean island country.

Three professors whose scholarship focuses on the tumultuous history and politics of this nation – Marlene Daut, Laurent Dubois and Robert Fatton – have been providing background and suggesting possible next steps, but at the same time are surprised at the mystery of who carried out the attack and who’s leading the country, saying it’s a dangerous time for Haiti.

Moïse and his wife, Martine, were at home outside Port-au-Prince Wednesday after midnight when unknown, heavily armed assailants broke in, killing the president. Martine was seriously wounded and is being treated in a Miami hospital.

The background to the situation was still unfolding as of Friday morning, when the investigation spread to international influences from Colombia, and the group of suspects includes two Haitian Americans.

Moïse had been in office for four years following a yearlong delay post-election, and his fifth and final year had been contested after he declared rule by decree and dissolved the Haitian parliament earlier this year. He had planned to hold a constitutional referendum and elections later in the year. Moïse had appointed Ariel Henry, a neurosurgeon, to become prime minister, but Claude Joseph, who has held the office just since April, said he is in charge and imposed martial law. The political arena is rife with more complications from differing constitutions and interpretations, especially on the line of succession.

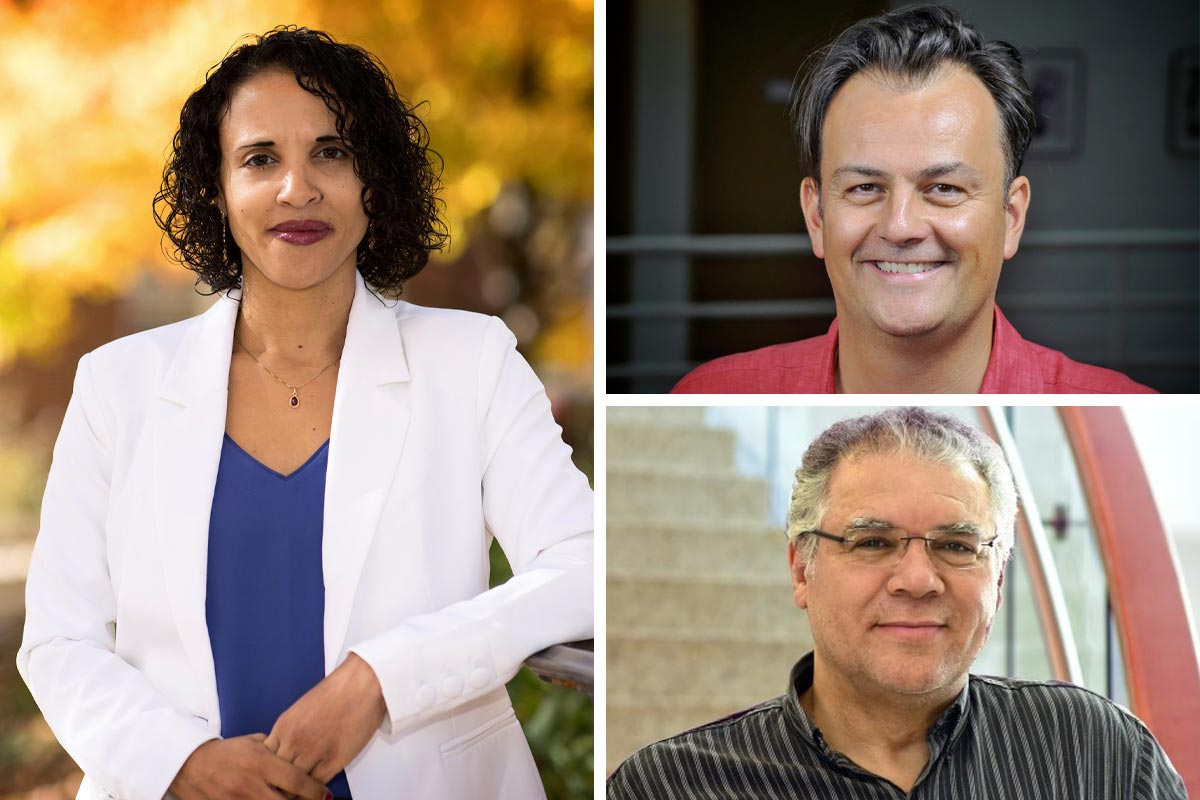

Fatton, a Haitian politics professor; Dubois, a historian of Haiti and co-director of UVA’s Democracy Initiative; and Daut, a professor of African diaspora studies in the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African and African American Studies, agreed that solutions need to come from within Haiti, as uncertain as that seems at the moment.

Marlene Daut, left, Laurent Dubois, top right, and Robert Fatton are providing commentary as Haiti deals with the assassination of its president in tumultuous times. (Photo of Daut by Dan Addison, University Communications; Dubois and Fatton, contributed)

The country is located about 600 miles southeast of Florida, sharing the island of Hispaniola with the Dominican Republic. Hispaniola lies between Puerto Rico to the east and Cuba and Jamaica to the west. Haiti has been in turmoil recently: Moïse had been accused of corruption, and possibly having ties to armed gangs that control or are fighting for areas of Port-au-Prince; his constitutional successor was supposed to be the Supreme Court chief justice, but he died of COVID not long ago – one consequence of the serious level of the pandemic. The COVID pandemic is spreading and the country has barely begun vaccinating people.

In addition, the country still hasn’t recovered from a devastating 2010 earthquake that killed more than 300,000 people and left almost 1.5 million homeless.

Reports say the assailants might have been foreign mercenaries – speaking English and Spanish, when most Haitians speak French or Creole – but were heard to yell that they were from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, which the U.S. said is false.

The U.S. Embassy has closed and the Dominican Republic shut its border with Haiti.

Dubois, John L. Nau III Bicentennial Professor of the History & Principles of Democracy, is the author of many books, including “Freedom Roots: Histories from the Caribbean” and “Haiti: The Aftershocks of History.” He told NBC News, “In general, Moïse has been consolidating power around himself increasingly over the past years, which has created a deepening crisis of governance. The refusal to step down, which was based on conflicting interpretations of the Constitution, was one example of that, but he also ordered a number of arrests of prominent activists.”

More than a dozen activists, including Dr. Marie Antoinette Gautier, a former presidential candidate, were arrested in February, accused of plotting a presidential coup.

Fatton, a Haitian politics professor, said he was “just dumbfounded by the event,” because despite Haiti’s political instability and attempted coups in the past, this level of violence resulting in assassination was rare.

“The future is totally uncertain,” Fatton, who was born in Haiti, told the Los Angeles Times. “Without a local solution involving a government of national unity, there is a real danger that the country could descend into chaos.”

The only other time a president was assassinated, the U.S. military occupied Haiti to protect its commercial interests from 1915 to 1934. American agricultural business benefitted, but kept Haitian workers in poverty with low wages.

“The last time a Haitian president was assassinated, in 1915,” Dubois wrote in email, “the U.S. launched a 19-year occupation that had disastrous and long-term results, whose effects are still felt today.”