Sydney Collins’ four years studying art history at the University of Virginia culminated in an Australian Aboriginal ceremony that few in the art world have been privileged to witness.

Collins, who interned and later worked at UVA’s Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection while a student, flew to Australia two months after graduating in May, accompanied by Kluge-Ruhe’s director, Margo Smith. They were the only American representatives to attend a historic summit, known as the “Makarrata,” that brought together Yolngu people from central Arnhem Land in Australia’s Northern Territory and art museums displaying their work.

“In Aboriginal culture, a Makarrata is a reconciliation between parties after a dispute,” Smith said. “In this case, the dispute was not a particular incident, but really a history in which museums and individuals had removed objects from Aboriginal communities – sometimes with authorization, sometimes without.”

The Kluge-Ruhe Collection was the only American museum represented, as Smith and Collins joined representatives from two European museums and 17 Australian institutions Aug. 11 to 14 in the Milingimbi community in Australia’s Crocodile Islands. The Makarrata, organized by Lindy Allen of Museum Victoria and Louise Hamby of Australian National University, was part of an Australian Research Council Linkage grant awarded to those institutions and the Milingimbi community.

Representatives witnessed traditional ceremonies associated with the ritual of the Makarrata and met with Yolngu artists and community members to discuss opportunities for collaboration. They also paid tribute to the late Joseph Gumbula, a leading Yolngu authority on global collections who instigated planning for the Makarrata.

According to Smith, the gathering was a historic step forward.

“I don’t believe anything similar to this has ever happened,” said Smith, who received grants from UVA’s Vice President for Research and Center for Global Inquiry and Innovation to research and participate in the Makarrata.

“Museums have regularly consulted with indigenous communities, but this was different in that it was instigated by the community, inviting major museums around the world to come and talk with them,” she said.

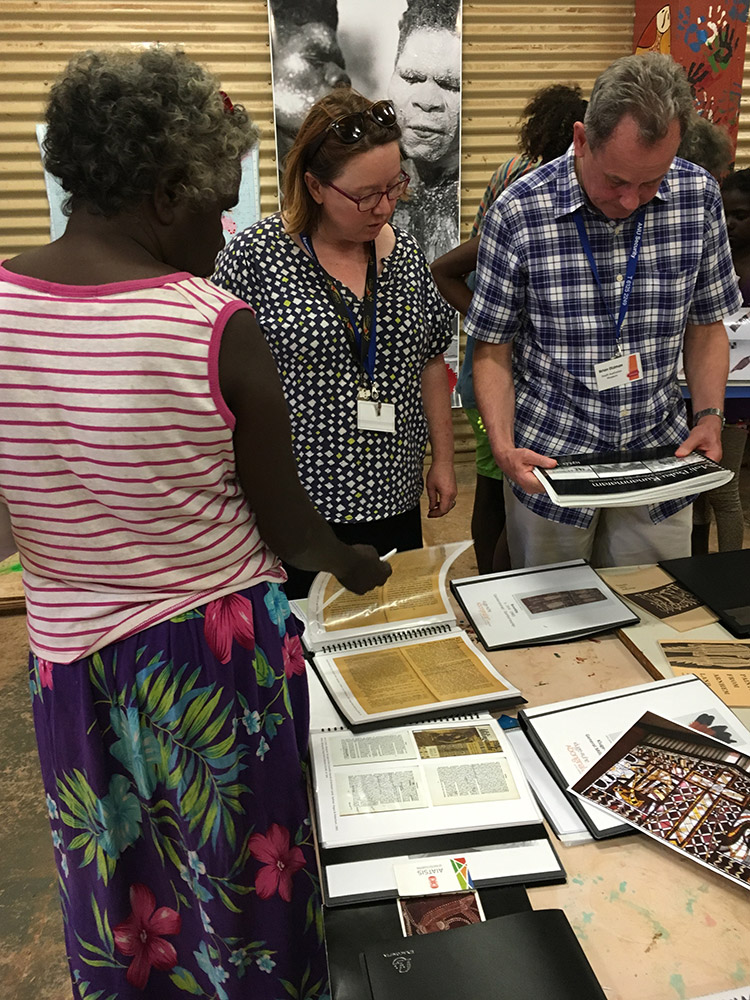

Sydney Collins, third from right, with members of the Milingimbi community during the Makarrata. (Photo courtesy of Margo Smith).

Collins was the only student to attend the Makarrata. She earned a Minerva Award from UVA’s College Council to partially finance the trip, which dovetailed with her Distinguished Major thesis project examining how digital databases can foster relationships between museums and artist communities.

“A big theme of the Makarrata was creating a new museology, as so much of the history of museums and collecting has been what the museum and the Western world can get out of a community,” Collins said. “I think it is so much more meaningful if collaboration is sustained for longer than just an exhibition, and I am really interested in how digital technology can help sustain those connections.”

Members of the Milingimbi community and representatives from other museums browsed archival material from the Kluge-Ruhe Collection.

In Milingimbi, Collins and Smith shared collections and archival materials compiled into books on five artists who feature prominently in the Kluge-Ruhe Collections. After their presentation, one Yolngu woman, Judy Lirrinyin, told Collins and Smith that one of the artists, Binyiniyuwuy, was her father. They gave her the book about her father and showed her a short film from the Kluge-Ruhe collection that featured her father and his fellow artists.

“She showed us the information she had gathered about her father from other institutions,” Collins said. “It was a really meaningful moment, and really great to be able to listen to her talk about her father.”

It was just one of many new relationships forged during the four-day gathering, relationships that Smith believes are critical to the Kluge-Ruhe’s mission of sharing Aboriginal art with UVA students, the surrounding community and the nation.

“Whenever the artists are involved in what we do here, we find that our visitors’ experience and our students’ experience is far richer,” Smith said. “The people we met are very generous and eager to teach outsiders about their culture, and we need to give them the opportunity to teach students who would like to learn from them.”

Given the distance between Charlottesville and Milingimbi, many of those opportunities could be digital. During her time at the museum, Collins has been working on digitizing the Kluge-Ruhe’s collections and archives, a project that Smith plans to continue.

“We are hoping to develop our digital presence much more,” Smith said. “This was a first step in talking to the community about what they would like to see and be able to access online and how we can best tell the stories of the artists and the archived material.”

For Collins, the Makarrata was also a first step in building her post-graduation career in the museum world that she grew to love during her time at UVA. After finishing her work with Kluge-Ruhe this week, she will move to Washington, D.C. to start an internship with the National Museum of the American Indian, part of the Smithsonian Institution.

“I like to think that museums are an optimal meeting ground between cultures,” Collins said. “Everyone has a lot to learn, and for the general public, museums are a great place to start to learn about people who are different from you.”

Media Contact

Article Information

August 31, 2016

/content/uva-student-director-attend-rare-aboriginal-art-makarrata-australia