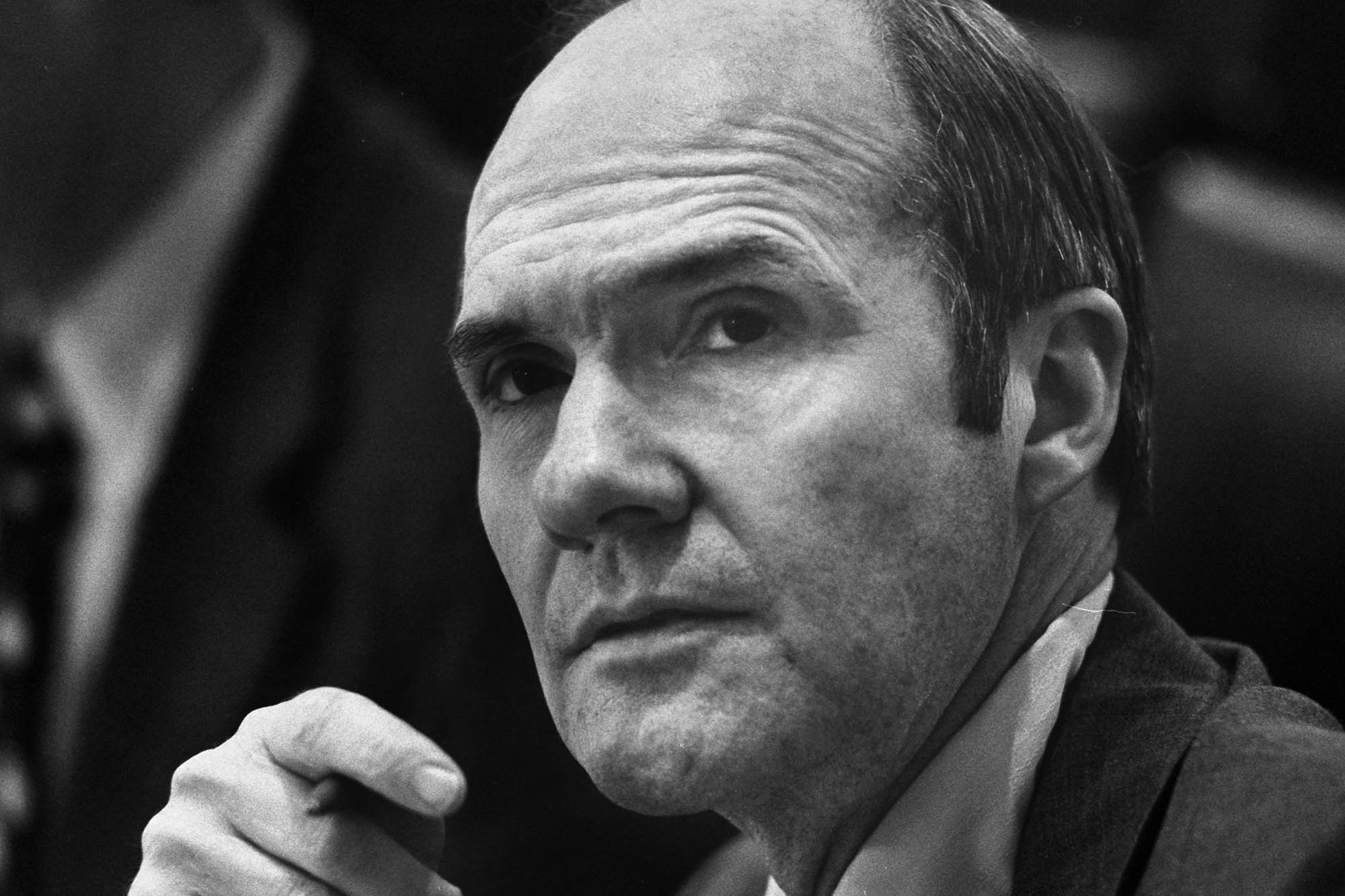

Twenty years ago, Brent Scowcroft sat down for two days of extensive interviews as part of the University of Virginia Miller Center’s George H.W. Bush Oral History Project. But unlike an earlier session for the project, Scowcroft had an important condition: The interview – not only his words, but even the fact it had occurred – was to be kept private.

Last year, the former national security adviser gave the Miller Center permission to publish his secret oral history posthumously. And after Scowcroft died Aug. 6, the center released the material, offering the public and scholars alike new revelations about the end of the Cold War, the Gulf War and the inner workings of the Bush administration.

The agreement is not as unusual as you might think, said Russell Riley, co-chair of the Miller Center’s Presidential Oral History Program and one of the nation’s foremost experts on elite oral history.

“You get far more honest recollections, far more candid answers to your questions, when the subjects know they will have complete control of their memories,” he said. “We don’t want them to censor themselves beforehand. Ironically, you generally end up with more detailed information in the public record if you allow interviewees to review their words and determine the date of release than if you treat the sessions as open, on-the-record conversations.”

Such was the case with Scowcroft, and much of the questioning by the Miller Center’s Philip Zelikow, who was also a member of the Bush 41 administration, and James McCall, of the Bush Presidential Library Foundation, focused on the Gulf War, which pushed Iraqi troops out of Kuwait in 1991 without toppling dictator Saddam Hussein.

In the secret session, Scowcroft admitted that concern over oil factored into the decision: “Iraq, with that much additional control over especially OPEC [the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries] reserves, could have threatened the world economy dramatically.” But more important were questions of the American role in the world following the demise of the Soviet Union. Scowcroft said:

[W]e were trying to set up a method of behavior for the post-Cold War world. We wanted to behave in a way – and use the UN in a way – which would set a pattern for the post-Cold War world in dealing with aggression. Which is one of the reasons that we worked so hard at making the UN work in this case, and one of the reasons why we were religiously observing the dictates of the international community. … We talked about one of the reasons – and that is setting a pattern for behavior, and how the United States would relate to the rest of the world. That is a cooperative leadership role, not a unilateral role.

Wary of an expanding conflict, Scowcroft offered a realist’s logic for leaving Hussein in place: “It would be satisfying to get rid of him – but we still have forces in Korea! Fifty years after the war in Korea. In many cases, in foreign affairs, you can’t solve problems. You manage them, you reduce them to the point where they don’t get to be crises.”

Scowcroft also revealed what the United States would – and would not – have done in the event Hussein had used chemical weapons against American troops: “We decided that, in fact, we would not respond with nuclear weapons if he used weapons of mass destruction of any kind. Instead, we would expand the target list. We did not explicitly threaten him with a nuclear response.”

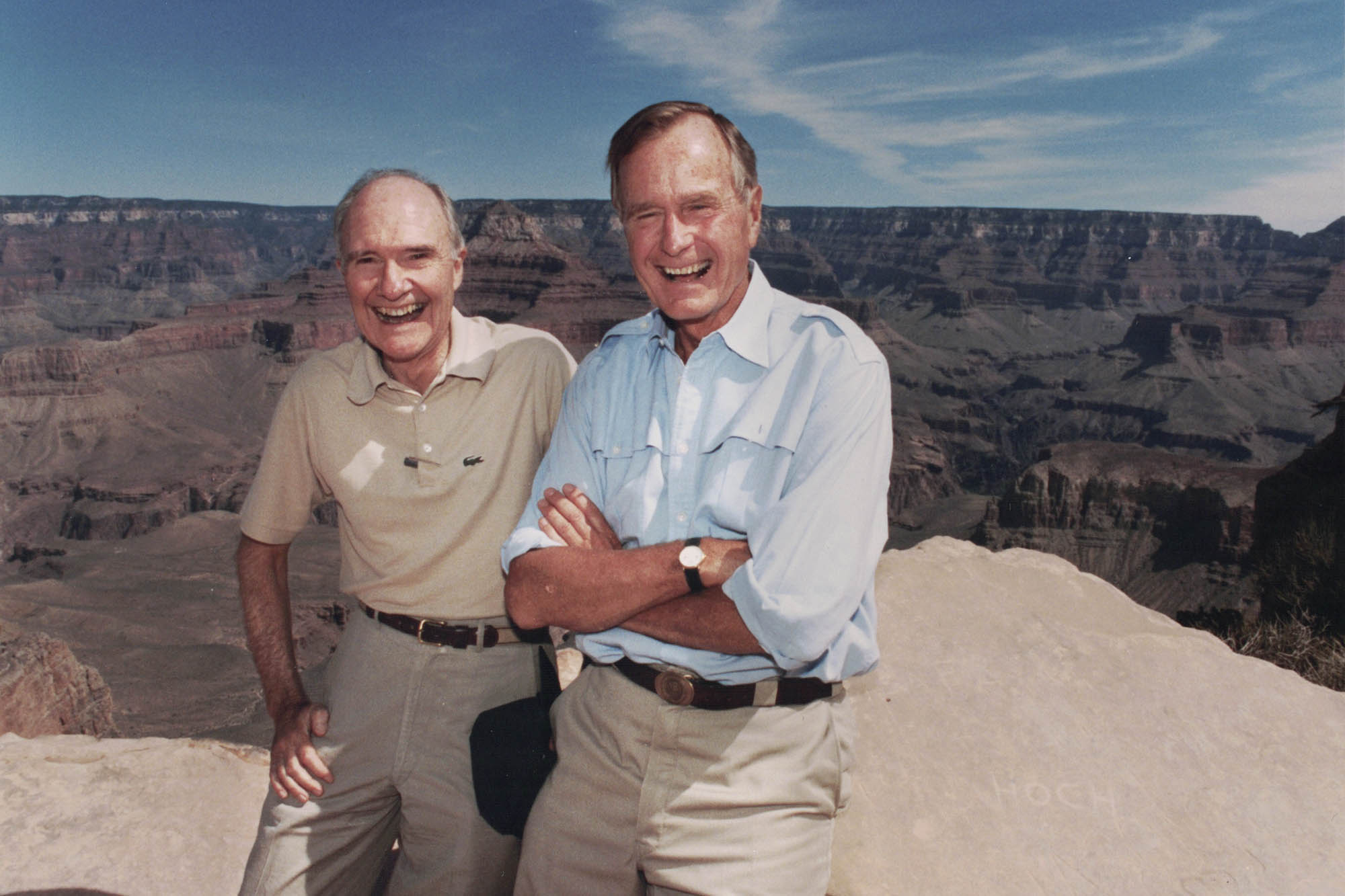

Scowcroft, left, with President Bush at the Grand Canyon in 1991. Scowcroft said Bush’s “people skills” were an asset to his presidency. (Photo courtesy George H.W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum)

At the end of the interview, Scowcroft delved into the personality of the first President Bush, a close personal friend, calling his “people skills” his most outstanding quality: “He liked to talk to people and find out what they were thinking about and how they were thinking. That gave him an intuitive feel for policy, which you probably can’t get any other way. It was an enormous advantage. He used it constantly. He was always on the phone to people, one way or another. … [W]hen he came to people, with a real problem – when he wanted help – they were disposed to provide their support because they knew who he was and they had respect for the way he thought.”

Perhaps the most touching revelation about the former president was an emotional sensitivity not apparent from public appearances:

He hides his emotions. He rarely says, “Thank you, that really meant a lot to me – that was terrific, what you did.” Why? Because he chokes up so quickly – it’s an agony for him to speak at a funeral or something. … [A]s a matter of fact, if you look at him in a public speech or so on, he comes across as slight patrician and austere. Unlike [his son] George W., who’s more like Clinton or Reagan. Bush is not that way. But he’s not that way because he is austere and patrician, but because he doesn’t want to risk getting too close to his emotions – because he gets very embarrassed if he breaks down, and he does it so easily.

To a historian like Zelikow, the White Burkett Miller Professor of History and Wilson Newman Professor of Governance, the information is invaluable.

“Together [with Scowcroft’s first oral history, released in 2011] they are a unique, and candid, personal memoir of Scowcroft’s experience in the Bush 41 administration,” he said. “The material is a lasting testament to some of the qualities that made Scowcroft so effective in public life.”

“A lot of these key figures won’t end up writing memoirs,” Riley said. “These interviews essentially serve as their memoirs. And in many cases our work, especially the extensive briefing book we prepare, ends up reminding them of incidents they had long forgotten. But none of that would be possible without the trust they can feel confident placing in us. It is probably our most important asset.”

For a detailed look at foreign policy in the Bush 41 administration and Scowcroft’s role, watch the new Miller Center documentary, co-produced by VPM and directed by Lori Shinseki, “Statecraft: The Bush 41 Team,” on PBS.

For more insights from Scowcroft’s secret oral history, read Peter Baker’s article, “Regrets? Even Brent Scowcroft Had a Few,” in the Aug. 12 edition of The New York Times.

Media Contact

Article Information

August 19, 2020

/content/uvas-miller-center-releases-secret-brent-scowcroft-oral-history