Nearly two years after Virginia rolled out a model policy to improve local law enforcement agencies’ eyewitness identification procedures, the vast majority of agencies across Virginia have failed to implement the best practices, according to a statewide survey conducted this spring by University of Virginia law professor Brandon Garrett.

Of 144 law enforcement agencies whose policies Garrett reviewed, only 6 percent had implemented the state’s new model policy, while 58 percent relied on an outdated policy from 2005 and 27 percent had an outdated policy from 1993.

One-fifth of agencies lacked any eyewitness identification policy whatsoever – in violation of a 2005 statute requiring a written policy, Garrett found.

“Many people have been working to improve lineups in Virginia – that was the theme of the Virginia Journal of Criminal Law Symposium [at U.Va. Law] last spring – but so far most police agencies have not adopted the recommended best practices,” said Garrett, a leading expert in wrongful convictions.

Garrett – who helped develop Virginia’s overhauled policy for police lineups and eyewitness identification that was published by the state’s Department of Criminal Justice Services in fall 2011 – obtained the information on the local law enforcement agencies’ compliance via a survey conducted between February and April, as well as from Freedom of Information Act requests filed by U.Va. law students working with the Virginia Innocence Project Student Group.

Aurora Heller, a rising second-year law student at U.Va. who is coordinating the Freedom of Information Act requests for the organization, said the Virginia Innocence Project Student Group sent letters requesting information to more than 300 agencies across Virginia last fall.

“The letter asked for policies regarding eyewitness identification procedures, interrogations and retention of evidence,” she said. “We are still in the midst of cataloging responses, but the hope is to eventually have a website created and a report written describing our findings.”

When police departments do not use the best eyewitness identification practices, there can be serious consequences, Garrett said. Of Virginia’s 16 DNA exonerations, 13 involved eyewitness misidentification.

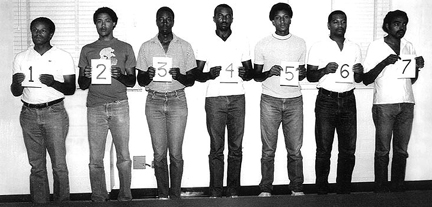

Most police agencies in Virginia continue to lack “blind” lineup procedures in which the police officer running the lineup does not know which person in the array is the actual suspect, Garrett said.

Less than one-third, or 42 of Virginia’s 144 policies, require blind lineups; another 16 say blind lineups are optional.

“Blind lineup policies are the most crucial reform and should be adopted universally,” Garrett said. “They are central to the new model policy, and training on it … provides simple ways for agencies of all sizes to adopt blind or blinded policies.”

In fact, he found, many police departments have “highly error-prone” policies for eyewitness identification. Thirty-three agencies require or make it optional to use sequential lineups – when a police officer shows pictures to a witness one at a time – but without blind procedures in place, Garrett said.

“Such policies may be even more error-prone than having adopted no changes at all,” Garrett said. “A sequential lineup prolongs the interaction with the administrator (“Is this the one? Is this the one? Or is this the one?”). A nonblind procedure may be far more prone to influence by the expectations of the administrator and may lead both to more identifications of fillers [photos of people who are not suspects], and other mistakes – even misidentifications of innocent suspects.”

Many of the agencies have “highly incomplete and inadequate” policies, Garrett said. Many of the agencies have adopted none of the major reforms called for in the state’s model policy. Of these agencies, 41 have only brief policies with no meaningful instructions for carrying out live or photo lineups, he found.

Only 85 law enforcement agencies require that standard instructions be given to the eyewitness, he said.

And very few policies give instructions on how to record lineups, with only 14 departments suggesting video as an option and only 11 suggesting audio.

Only nine agencies adopted the current Department of Criminal Justice Services model policy, and only those agencies reported making the “folder shuffle” system available as an option. “The folder shuffle is a simple way for a small agency to make a lineup blind, by putting photos in folders, adding a few blanks, shuffling them and letting the eyewitness look inside without the administrator being able to see inside the folders,” he said.

Garrett’s findings will be included in a forthcoming paper, “Eyewitness Identification and Police Practices: A Virginia Case Study,” that will be published by the Virginia Journal of Criminal Law. The results, he said, indicate that legislative action may be necessary to improve Virginia’s eyewitness identification procedures.

“Lawmakers in Virginia have been reluctant to force agencies to adopt any particular lineup policy, since they assumed that with sound model policies agencies would voluntarily adopt the best practices,” he said. “If that is not happening, then stronger measures are needed.”

Media Contact

Article Information

August 26, 2013

/content/va-police-agencies-fail-improve-witness-id-policies-uva-law-professor-finds