Editor’s Note: This article has been adapted from “Sabato’s Crystal Ball,” a comprehensive website run by the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics that features regular, detailed analysis of elections around the country.

In November 2016, Virginia will easily be one of the most-watched states in the general election contest. The Old Dominion’s 2008 and 2012 presidential vote most closely matched the national popular vote, and it has become a pivotal swing state in a polarized country that doesn’t have many of them.

However, some might not attach as much overall importance to Virginia’s presidential primary. Yet, at least on the Republican side, the commonwealth may hold a great deal of meaning. Many aspects of the state’s electorate are sufficiently favorable to Marco Rubio that he has at least an opportunity to defeat Donald Trump if things fall his way. So what can we expect in both parties’ elections? Read on for a preview.

The Republicans

Delegates at stake: 49 statewide delegates (13 at-large, three automatic, and 33 congressional district delegates)

Allocation method: Proportional allocation by statewide vote (roughly 1 percent threshold) for all delegates

The state of play in the GOP race is pretty clear from a national perspective: Trump is at least a modest favorite almost everywhere. Given Trump’s performance so far, it will be a surprise if he doesn’t capture Virginia by some margin. Still, if anyone is going to beat Trump in Virginia, it might be Rubio, if he finally gets his act together and the party does, too.

Although the business mogul may be slightly ahead in Virginia, it’s unclear how big a lead Trump might or might not have in the Old Dominion. There hasn’t been much recent polling in the commonwealth, but in mid-February the Wason Center at Christopher Newport University found Trump ahead of Rubio by six points, 28 percent to 22 percent, with Ted Cruz in third at 19 percent.

Since that survey was completed, Trump has won the South Carolina primary and the Nevada caucus. So heading into March 1, Trump keeps winning, Rubio has back-to-back runner-up showings buoying him as he anxiously waits for the field to further winnow, and Cruz is losing steam after consecutive third-place finishes.

Trump’s strengths in Virginia will likely reflect those he has exhibited so far, with stronger support from voters with lower education levels and many white evangelical Christian voters, although his support is far from limited to just those groups. Still, Rubio has the most obvious path to best Trump: outdistancing the billionaire in the populous Urban Crescent, the curving array of metropolitan areas formed by the Northern Virginia suburbs outside of Washington, D.C., the greater Richmond region, and Hampton Roads in the state’s southeast. Helping the Florida senator will be the heavier concentration of highly educated voters in those areas. Cruz will hope that he can improve his support among evangelicals and gain an edge in a still-fragmented field, though his South Carolina performance leaves us skeptical that he can manage that feat. Lastly, John Kasich will hope to also win over support among voters in the Urban Crescent, but his route to victory is hard to see.

Let’s start with a look back at the 2008 GOP presidential primary, shown in Map 1. Although there was a 2012 primary, stringent ballot access restrictions led to only Mitt Romney and Ron Paul qualifying, making it a less useful marker. Given Romney’s edge in the race, fewer than 300,000 voters participated in the 2012 GOP presidential primary versus almost 500,000 people in the 2008 edition. In the latter, John McCain bested Mike Huckabee 50 percent to 41 percent, with Ron Paul and Mitt Romney (who had withdrawn a few days earlier) winning most of the remaining votes.

Map 1: 2008 Virginia Republican presidential primary. Source: Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections [Source: Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections]

Notice that, for the most part, McCain performed better in the Urban Crescent than he did in the rest of the state – and particularly in Northern Virginia, where he won 60 percent of the vote. Connecting this to 2016, Rubio’s strongest areas in Iowa and South Carolina were in counties with major population centers, such as Polk County (Des Moines) and Charleston County (Charleston). While Rubio hasn’t won these denser localities* by large margins – and certainly couldn’t win Virginia’s with the percentages McCain did in a two-man race – it’s notable that those are the places where he’s finishing first. In 2008, 69 percent of the Virginia GOP primary vote came from the three major population centers and their surroundings. If Rubio can show strength in them as the de facto establishment candidate, particularly in Northern Virginia, it could give him a chance statewide.

Huckabee’s religious appeal matches Cruz’s to a large extent, but the Arkansan’s economic populism is more akin to Trump’s. Therefore, it’s easy to imagine Trump and Cruz performing better than Rubio in the western reaches of the state. While these are less-populated areas, they are more strongly Republican and are an important GOP vote pool in any election. In 2008, areas outside of the Urban Crescent (mostly west of Richmond, along with the Northern Neck and Eastern Shore) cast 31 percent of the GOP primary vote, more than any one of the three metropolitan zones did individually.

Virginia is not as heavily evangelical as states further to the South, but white born-again Christians did make up 40 percent of the Republican primary electorate in 2008 (and 44 percent in 2012). Unsurprisingly, these voters went strongly for Huckabee, 62 percent to 30 percent, over McCain. Still, as we’ve seen in South Carolina, Trump can best Cruz for support from these voters, and that bodes poorly for Cruz’s chances in the Old Dominion. As shown in Map 2, Southside and parts of western Virginia tend to have the largest number of evangelical adherents. One can expect these areas to perform strongly for Trump and Cruz on March 1. But don’t forget about Rubio with white evangelicals: In Iowa, he won about the same percentage as Trump (21 percent) and won 22 percent of them in South Carolina. Importantly for Rubio, Virginia’s lower share of white born-again Christian voters compared to other Southern states gives Cruz and Trump less of a base that they have won over in earlier contests.

Map 2: Virginia Evangelical Protestant Rates of Adherence per 1,000 people, 2010. [Source: Religion Congregations and Membership Study (2010) from the Association of Religion Data Archives]

Beyond population density and religion, education levels will certainly play a role in where different Republican candidates find pockets of strength. Entrance and exit polls have shown Trump winning significantly larger percentages of the vote among those who are not college graduates than those who are, most notably in South Carolina, where there was a 16-point difference in Trump’s support between the two groups. We can likely expect more of the same in Virginia.

Conversely, Rubio has generally performed better with college graduates, so areas with larger numbers of such voters could prove to be more fertile ground for him. In the lower-turnout 2012 GOP primary, 58 percent of Republican voters were college graduates, the highest of any state with primary exit polling that cycle; in 2008’s buzzier contest, 56 percent were. Map 3 below lays out the college graduate (associate’s degree or higher) data for Virginia localities. Once again, much of Southside and southwestern Virginia could produce many votes for Trump as well as Cruz, who has also performed better among non-college graduates. The clustering of higher percentage areas in Northern Virginia and Richmond show why those might be Rubio’s strongest areas, corresponding to his strengths in metropolitan regions.

Map 3: Virginia college graduate percentage by county, 2014. [Source: U.S. Census Bureau’s 2014 American Community Survey (5-year estimates)]

All in all, Trump has so far won sufficiently broad support from all groups and geographical areas in every state that has voted, and Virginia will probably be little different. The main question is, can Rubio run up his margins in the Urban Crescent? Or could Kasich impede that effort by attracting similar types of voters? Symbolically, Rubio could really use a win in a state like Virginia if he’s going to be viewed as a truly credible threat to Trump. The potentially competitive contest could be his best chance of actually winning a primary on Super Tuesday.

However it works out, expect all of the candidates still in the race to win delegates: The Republican Party of Virginia went with a proportional allocation system (based on the statewide vote) that has no threshold, meaning that all the candidates still in the race could qualify for at least one delegate as long as they win 1.087 percent of the vote or more.

The Democrats

Delegates at stake: 95 (of 109 total) — 33 statewide, 62 congressional district delegates

Allocation method: Proportional allocation by statewide and district vote (15 percent threshold)

The race between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders is, in many ways, more straightforward than the GOP contest. Democratic primary voters will have a binary choice on March 1, unless they want to vote for Martin O’Malley, whose name remains on the ballot. As in most Southern states, Clinton will be a decent favorite in Virginia. While we only have two recent polls to consider, both show her up by double digits. There are three things to keep in mind when thinking about the Democratic matchup: nonwhite voters, Clinton’s 2008 performance and the delegate situation.

As we previously described – and the Nevada caucus demonstrated, to some degree – one of Clinton’s chief advantages in the Democratic primary is her strength among nonwhite voters, particularly African-Americans. Although she didn’t win the Silver State contest by much, Clinton garnered backing from three-fourths of black voters and probably won, perhaps quite narrowly, among Hispanics as well, though the entrance poll suggested otherwise. In other diverse states to come, such as South Carolina’s primary (majority African-American), Clinton should be favored to win.

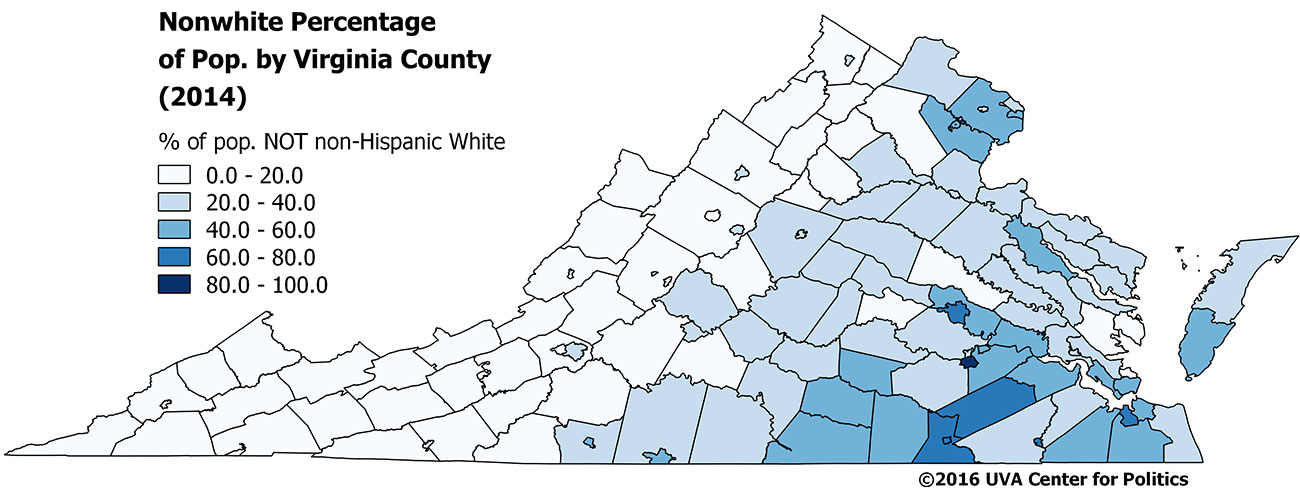

Virginia, too, should have a large level of nonwhite participation: In 2008, 38 percent of Democratic primary voters were nonwhite, with black voters importantly making up much of that (30 percent of total). Map 4 lays out the county-by-county percentages of individuals who are not non-Hispanic whites.

Map 4: Nonwhite percentage of the population by county, 2014. [Source: U.S. Census Bureau’s 2014 American Community Survey (5-year estimates)]

Given her high support levels from African-American voters, Clinton will probably do well in the Richmond and Hampton Roads regions, as well as in some more rural areas of the state, such as Southside and the Northern Neck. From the perspective of pure vote totals, Northern Virginia is probably going to be the fiercest battleground. The D.C. suburbs are diverse, but that diversity is more fragmented than in the rest of the state. For example, Fairfax County, by far the most populous locality in the state, is 53 percent non-Hispanic white, but the largest minority group is Asian-Americans (18 percent), followed by Latinos (16 percent), then African-Americans (9 percent). Thus, Clinton’s most certain base of support won’t weigh as heavily on the outcome there as in some other parts of the state (though note that Prince William County has a large African-American community). Moreover, Northern Virginia will likely have the highest number of liberal whites – Sanders’ strongest base of support – participating in the primary of any region, particularly in places such as Arlington County. This will be critical for Sanders: In 2008, 36 percent of the primary vote was cast in Northern Virginia.

In an interesting twist, it’s possible that Clinton will perform better in the eastern part of the state, essentially the opposite of her 2008 loss to Barack Obama. As shown in Map 5, Obama won every locality east of the Blue Ridge Mountains, save the small city of Colonial Heights. Clinton performed best in the western part of the state in 2008, especially Southwest Virginia.

Map 5: 2008 Virginia Democratic presidential primary. [Source: Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections]

Today, that region has become a political red sea, but in 2008 there were more votes from Southwest Virginia in the Democratic primary than the Republican primary. This was partially the result of the very competitive nature of the Obama-Clinton contest – there were twice as many votes in the Democratic primary as the GOP primary in 2008 – as well as the state’s open primary rules that eschew party registration and permit voters to cast a ballot in the party primary of their choice. But one has to wonder if many of the “Beer Track” voters who backed Clinton in 2008 will show up in 2016. It seems more likely that many of them might vote in the GOP primary this time around, given the juicier GOP primary and the strong Republican shift in that region. Therefore, the few voters who will cast ballots in the Democratic primary in the rural, southwestern parts of the state may actually be individuals who are more likely to support Sanders.

It’s difficult to know for sure, but a data point from outside of Virginia might hint at possible success for the Vermonter in that part of the Old Dominion: A new West Virginia poll, albeit one with a small sample size, found Sanders ahead of Clinton 57 percent to 29 percent in the Mountain State. It’s not Virginia, but culturally there are major similarities between Southwest Virginia and West Virginia.

Lastly, it’s worth noting the delegate rules in the Democratic contest. The national party rules require the state to use a proportional allocation system with a 15 percent threshold. Of the 95 “pledged” delegates at stake, 33 will be proportionally handed out by the statewide vote while the other 62 will be proportionally allocated by the vote in each of the state’s 11 congressional districts. The more Democratic the district, the more delegates it is assigned. Table 1 shows the breakdown of where Virginia’s delegates come from. Importantly, Virginia’s ongoing redistricting saga might have altered the delegate totals slightly in some districts, particularly the Fourth District, which went from being a 49 percent Obama district to a 61 percent Obama district. However, the Democratic Party of Virginia informed me that it will not be changing the congressional district delegate assignments and will use the old lines.

Table 1: Virginia’s Democratic delegate makeup

The proportional rules on the Democratic side will prevent one candidate from overwhelming the other in the Virginia delegate count, but based on the limited polling we have and the likely demographics of the electorate, it’s hard not to see Clinton as a favorite to win more delegates and to win statewide. A Sanders “win” might be keeping the margin to single digits statewide while winning some of those western districts and competing in Northern Virginia. Just like the Republican contest, the Democratic primary will be mostly decided in the Urban Crescent: In 2008, 77 percent of the votes cast came from the metropolitan areas of Northern Virginia, Greater Richmond and Hampton Roads.

* Throughout this article, the term “locality” is used generally to describe Virginia’s counties and cities. Virginia has an unusual local governance system that has led to it having a large number of “independent cities.” Whereas in most states a city is a part of the county – e.g. Chicago is part of Cook County – many Virginia cities are independent of the surrounding counties. For example, the county seat of Albemarle County is Charlottesville, but Charlottesville is an independent city with a separate governing structure from the county. Thus, Albemarle County and the City of Charlottesville have separate election results.

Media Contact

Article Information

February 25, 2016

/content/virginia-pivotal-primary