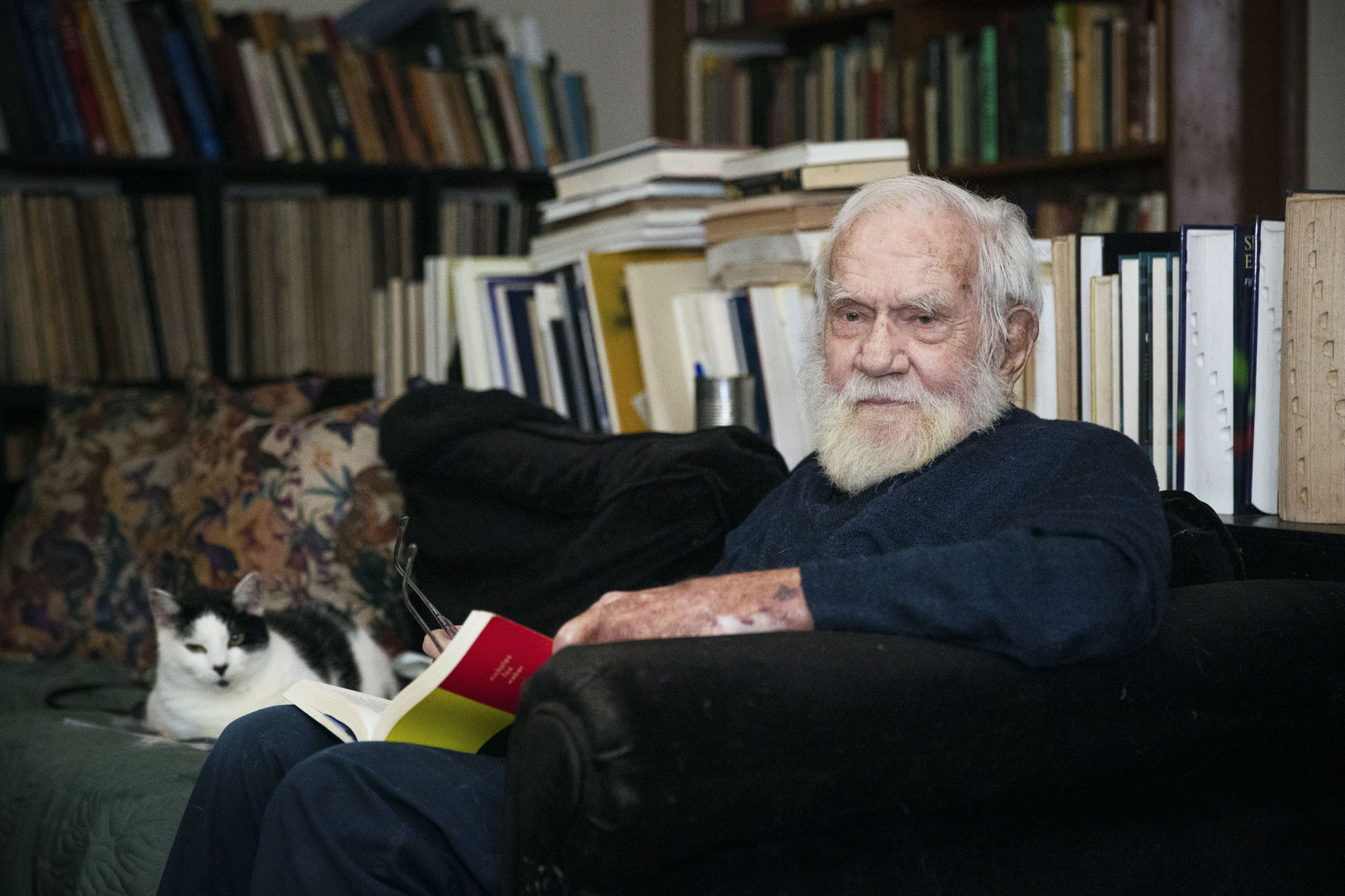

James Kavanaugh sits regally on his sofa, his walker nearby and his reading lamp at the ready, surrounded by more books than most people see. Still feisty and sharp at 95, Kavanaugh – retired warrior, retired doctor, retired professor – readily engages with visitors, recalling his roles in war and peace, a history he is now sharing with the University of Virginia community.

Kavanaugh, who flew 25 bombing missions over Europe as a B-17 radio operator, is the subject of a filmed interview that will air tonight for members of the Colonnade Club and local veterans affiliated with ParadeRest Virginia. The Colonnade Club is making this webcast available to the public at 7 p.m. on Veterans Day. Afterward, it will be available on the Colonnade Club and ParadeRest Virginia websites.

The event was organized and coordinated by Dr. Gregory Saathoff, a psychiatrist who trained under Kavanaugh and who is a co-founder of the ParadeRest Virginia organization. Saathoff interviewed Kavanaugh for the hourlong film, which is interspersed with archival footage and still shots from the World War II and UVA.

ParadeRest Virginia started as a project to assist the families of local active-duty military personnel. Its mission expanded to include the recording the personal histories of veterans for the Library of Congress’s Veterans History Project. Kavanaugh was the first veteran interviewed, about eight years ago.

“We call it ‘A Nickel for Your Story,’” Saathoff said. “I have spent a lot of time in the Middle East, and kids [there] would ask me about where I was from. I would show them a Jefferson nickel and say, ‘I live near this man’s house.’ We can take for granted the significance of this community until we highlight it for someone else.”

Kavanaugh is mildly amused with the presentation and said he took part in it because Saathoff asked him.

“Your own life never seems like anything unusual,” Kavanaugh said. “It is just the way you live. But Greg tries to see more in it, the coincidences, and the fact that the University has played a big part in my life.”

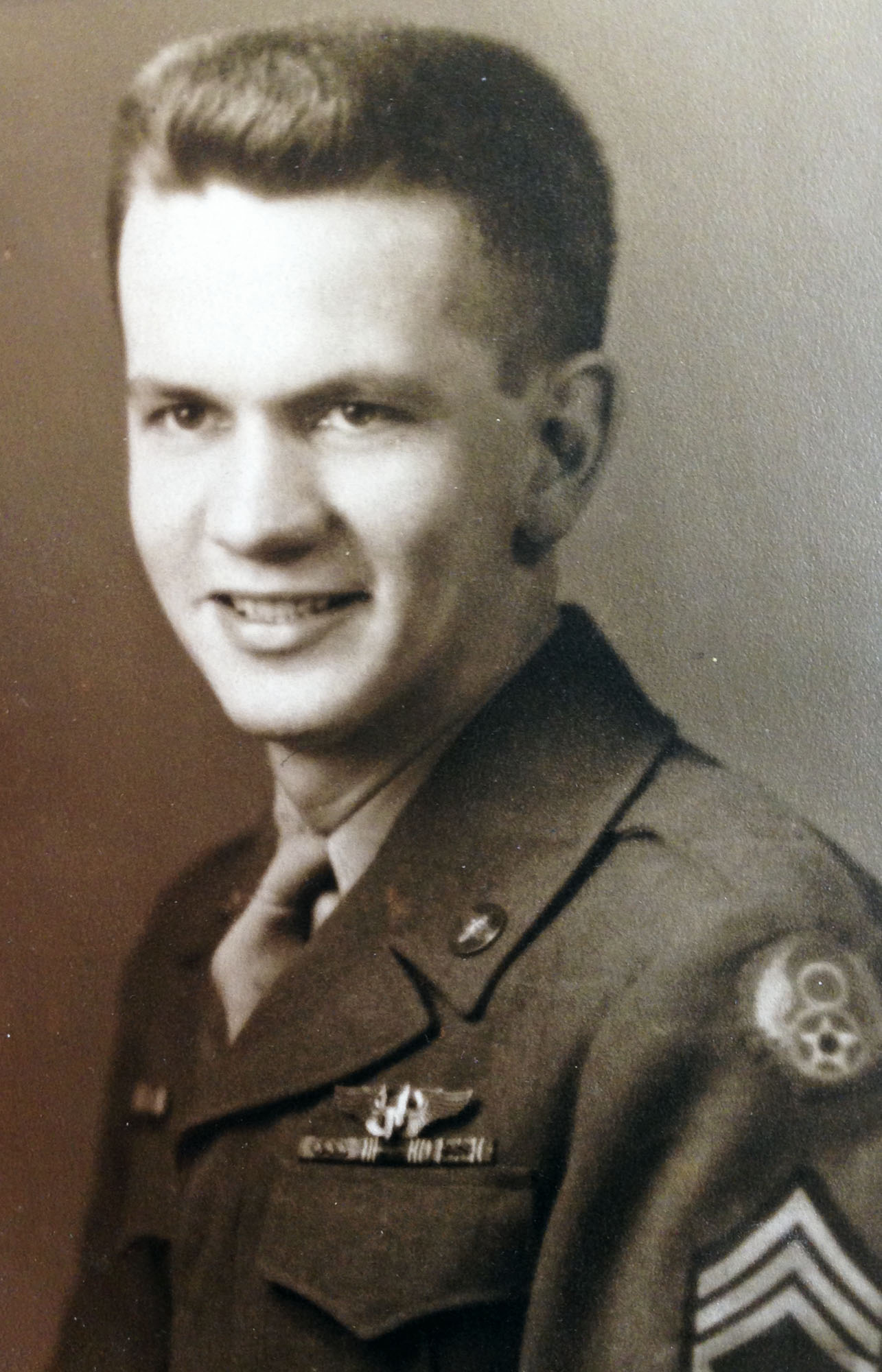

Despite his protests, Kavanaugh’s life is not uninteresting. Raised in Roanoke, he was drafted after graduating from high school in 1943. Because his father, a UVA Law School alunnus, flew during World War I, he signed up for the U.S. Army Air Force. His dependence on eyeglasses and poor depth perception kept him from the pilot’s seat, so he changed his training to radio operator.

“Because I had known older people who worked in commercial radio, I associated radio with that kind of work, not code,” he said. “My pattern recognition on sound was high and they told me I showed aptitude and they could teach me code. So they did, but I had not known that was what it was going to be when I agreed to become a candidate for radio operator.”

Kavanaugh shipped out from North Carolina to South Dakota for radio training.

“It was fall in North Carolina and it was cold in South Dakota by the time we got there,” he said. “The standard barracks, which was just a hut, had two stoves. In Sioux Falls, we walked into a barracks and noticed they had three stoves. The Army is a careful place and they take good care of you because you are an investment, but I figured they would not waste a third stove for no reason. That was going to be a really cold place, and it was.”

From South Dakota, Kavanaugh went to Yuma, Arizona, for gunnery training.

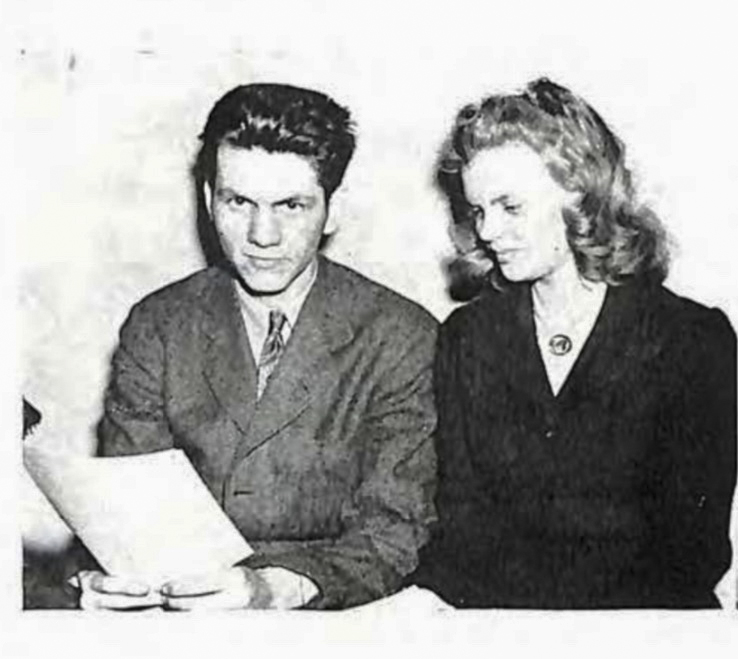

Kavanaugh with Lucille Townsend, editor in chief of “The Acorn” yearbook at Jefferson High School in Roanoke, 1943. (Contributed photo)

“I was very good at stripping guns blindfolded and putting them back together,” he said. “And I got the feeling they were going to try to get me to stay on the staff there in Yuma, so when they got to interview me, I would drop things on the floor and so forth and I didn’t demonstrate any qualities that would make them think I would be a good teacher. The usual feeling at that point was to get done with training to get into action. No one I knew was looking for a soft spot to hide out in. We were all young and frisky.”

The young and frisky Kavanaugh did get into action, flying in B-17s for the 8th Air Force in the European Theater, though by his account the “heavy lifting” had already been done by the time he became a cog in the machinery. The Allies were on the continent, Normandy in the rear-view mirror.

“In the 8th Air Force, their bragging point was that they had never been turned away from a target by enemy action,” Kavanaugh said. “They had been turned away by bad weather, so there was always a secondary target, but that meant that wherever you were told to go, you were expected to go, and you did.”

His crew participated in a 1,000-airplane raid over Germany, a massive mission that for Kavanaugh heralded the end of the war.

“My group, which was the 379th Heavy Bombers, led the largest mission on Berlin,” he said. “We were the lead group, and as we were flying out of Europe, the stream of bombers was still going in, and I had the feeling that no matter what happened, [Germany] would lose. No one could stand up to that. No one could. There were just too many. At that time, I didn’t think that civilians were being bombed and little children were going into air raid shelters. People were trying to kill us, so we were going to beat them to the draw.

“We were teenagers. The war in Europe was over before my 20th birthday. That’s what I mean by they could teach you a lot. I won’t say I was comfortable, but I knew what I was doing in a radio room and I could do what they expected of a radio operator. I didn’t necessarily like it, because they were losing people, other people.”

Kavanaugh as a young man in the U.S. Army Air Force in 1944. (Contributed photo)

Kavanaugh has always been a book collector, stacking peach crates on top of each other as a child to form shelves for his Big Little Books. He brought books along on deployment.

“I took a number of books into the military, but a plane crashed on take-off into our barracks and burned my books,” he said.

One of the books he carried to England with his was Leo Tolstoy’s “War and Peace,” a book he had started, but never picked up again after his copy was destroyed by the plane crash, thinking it a bad omen.

“I spent a lot of my passes in London, and Foyles bookstore would have whole sections for one subject, and it would be so thorough,” Kavanaugh said. “I would send a lot of books home because I had all this loose money.”

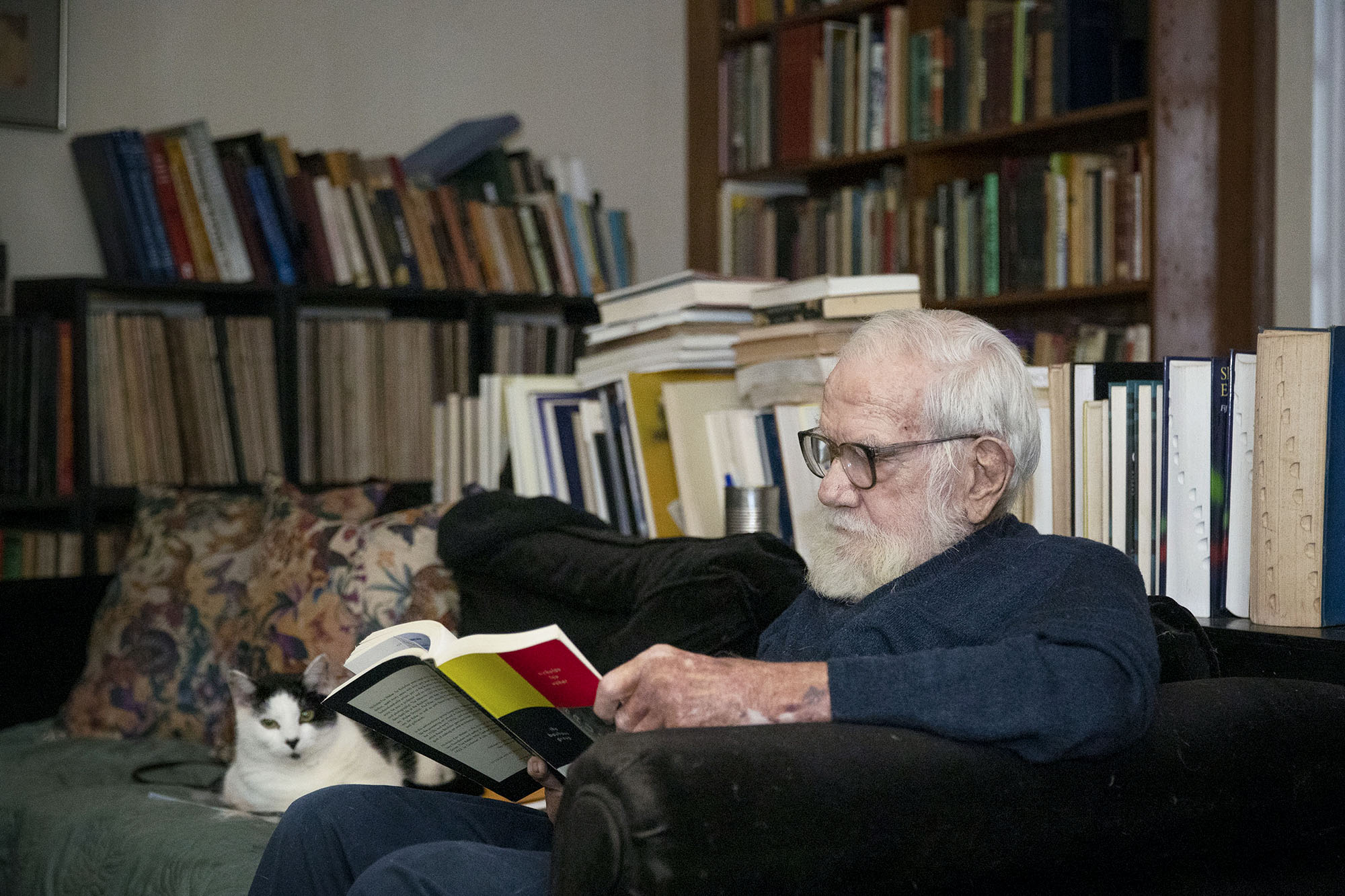

The walls of Kavanaugh’s current house are lined with full bookshelves and he added a wing to the building to act as a library.

“I have a section for fiction, for history and so forth,” he said. “I don’t read much fiction. Right now I am reading a book on Bauhaus because of the art scene in the ’20s. I keep a record in my head, since I was born in 1925, of what was active in ’25 – who was writing the plays who was painting the pictures and what were the movies then and what cars were selling. I don’t read one book at a time. I can balance a couple. I have a complete Shakespeare here – that fills in the gaps – and the Bauhaus, and under that I have a parallel New Testament with eight different translations, so when I read it I can compare and see if they use the same word and if it makes more sense if you use a different word and so forth.”

Kavanaugh is a book collector and the walls of his current house are lined with full bookshelves. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

For Kavanaugh, the war in Europe ended suddenly and then the war in the Pacific ended abruptly.

“We had disbanded as a bomb group and our ground crews had been shipped to the Pacific already to work on B-29s and the flying crews,” Kavanaugh said. “We were told we were coming back to the United States to be requalified on B-29s and then we were going to the Pacific. The future was all laid out that way, and suddenly the future stopped. They all of the sudden had too much of everything, including personnel. Too many blankets, too many tanks, too many trucks, and how do you get rid of all this stuff? And they had to let people go.”

After the Army, Kavanaugh returned to Virginia and to UVA, an undergraduate on the G.I. Bill, which covered tuition, books and gave him $75 a month on which to live. After the Army, which provided him shelter, clothing, doctor’s care and food, he had to reduce his expenses, so he quit smoking, which he thinks in retrospect was a good thing.

To augment his living money, he took a job at the Veterans Administration Mental Hospital in Salem, which sparked his career in psychiatric medicine.

“That was my first systematic interaction with mental patients, who were mostly veterans and mostly my age,” he said. “They were penned up because everything was lock-ward then and that was an eye-opener to me. They did not seem like lunatics. These were people you could talk to, who would show you pictures of their families; these are human beings. I became really intrigued by the idea that how could a person who looks completely normal, doesn’t limp, has no scars, be considered so poorly functioning that they can’t be allowed outside.”

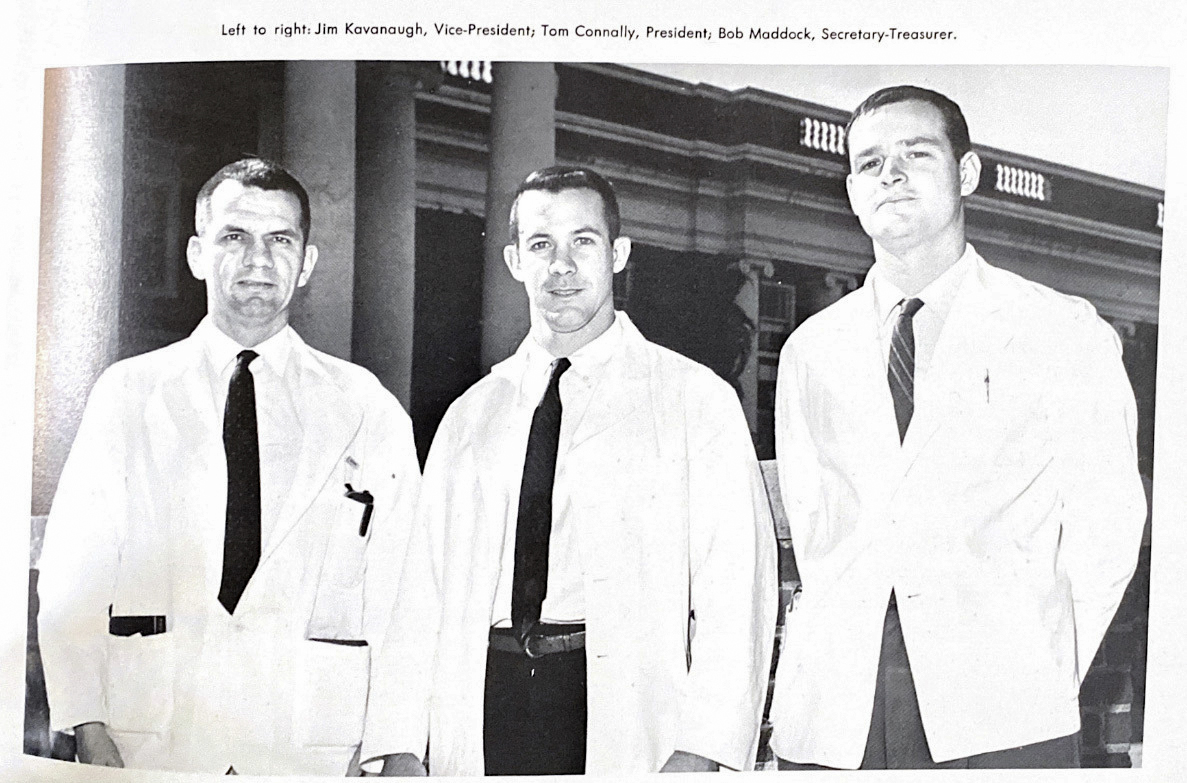

Kavanaugh as a fourth-year medical student at UVA, with fellow students Tom Connolly and Bob Maddock. (Contributed photo)

Because there was a small medical/surgical unit at the hospital and residents from the University Hospital and Medical School faculty used it for training, Kavanaugh got to know them. When he began asking them about the treatments for the patients, one of the residents, who later became a friend, encouraged him to apply to medical school.

“It never occurred to me that medicine was something that you learned the same as if you wanted to learn astrophysics,” he said. “They have classes and you take them, and they get harder and they tell you more and finally you are turned loose on a research project or something. It’s like the old Irishman who finally stumbles over a pot of gold. It was there all along, but I never knew where to look for it.”

After graduating UVA’s School of Medicine and completing his psychiatry residency here, Kavanaugh, his wife Anne, and their four children moved to Boston, where he completed a two-year child psychiatry fellowship at Harvard.

“I was one of the few who entered medical school knowing I wanted to do psychiatry,” he said. “I knew you had to study all this other [material] and it made sense, but I never ran into anything else that seemed to have the appeal. The brain is an amazingly challenging organization of cells and so forth. I’ve been using mine for 95 years and you can ask me something and most of the time I can remember, back to [age] 2, 2½.”

Child psychiatry became Kavanaugh’s specialty.

“When I went into psychiatry, I had only seen the VA and adults,” he said. “I didn’t know there was child psychiatry. And then when I did rotations in medical school, I saw pediatric patients and realized there were some who needed professional help. That threw me. I was drawn to the little folk because they are so sweet.”

After Boston, the Kavanaugh family returned to Virginia and he joined the faculty at the UVA School of Medicine, training students in child psychiatry, a discipline he said did not get a lot of respect from other doctors in the early 1950s. But then he noticed that several of his colleagues were asking him questions that related to their own children, so he knew he was reaching them.

“You have to humor them,” he said. “I saw a fair number of faculty children and I thought that was good that there was a place where they knew me.”

Kavanaugh enjoyed teaching because he likes getting to know people.

“I think by the time you get to post-graduate teaching, you really are just mentoring,” Kavanaugh said. “To me a good psychiatrist is going to develop his or her own skills and whatever brought them to it, and you can help with that. I never wanted to create another me or anything. But I thought I could help someone else to see [themselves].”

Saathoff was one of the people Kavanaugh mentored.

Kavanaugh and World War II B-17 pilot Jack Bertram at Alumni Hall in 2016. Albemarle resident Bertram flew 36 missions over Europe, including two runs on D-Day. Bertram turns 100 on Veterans Day. (Photo by Greg Saathoff)

“I have known Jim since I first came out here to train,” Saathoff said. “I knew that he had some military background, but he never talked about it. I know he’s a nice guy and an incredible child psychiatrist. As so many of my colleagues, I have learned so much from him. He is an intellectual who doesn’t resort to intellectualization. You would not believe how good this guy is with children. He could talk with them and kids just love the guy because he always seemed to know what was most important to them.”

But while Kavanaugh was good at talking with children, he did not share many of his war memories with his own children, who learned details of their father’s past from the video being shown tonight – in part, he said, “because they didn’t ask.”

“There is a good reason why the children don’t ask,” Saathoff said. “If their fathers were in combat, there are some unspoken painful memories and the children’s idea is to be protective. Their caring approach is as if to say, ‘When you are ready, you will let us know.’

“But sometimes that never happens. What we have found is that ParadeRest Virginia and its students and volunteers act as an intermediary. We make assumptions that there always will be time. What is amazing, and we have seen this so many times, is that families do not yet know the stories.”

Media Contact

Article Information

November 10, 2020

/content/war-and-peace-retired-faculty-member-recounts-air-combat-world-war-ii