More than four decades after burglars broke into Democratic National Committee headquarters, the Watergate scandal remains etched on the American psyche.

The name is so synonymous with wrongdoing that “-gate” has become an automatic suffix to describe new scandals as well. New Jersey Governor Chris Christie’s “Bridgegate,” former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s “Emailgate” and quarterback Tom Brady’s “Deflategate” are just a few recent examples.

In a new four-part series, the University of Virginia’s Miller Center will explore the in-depth history of Watergate and the lasting impact it’s had on the American political landscape.

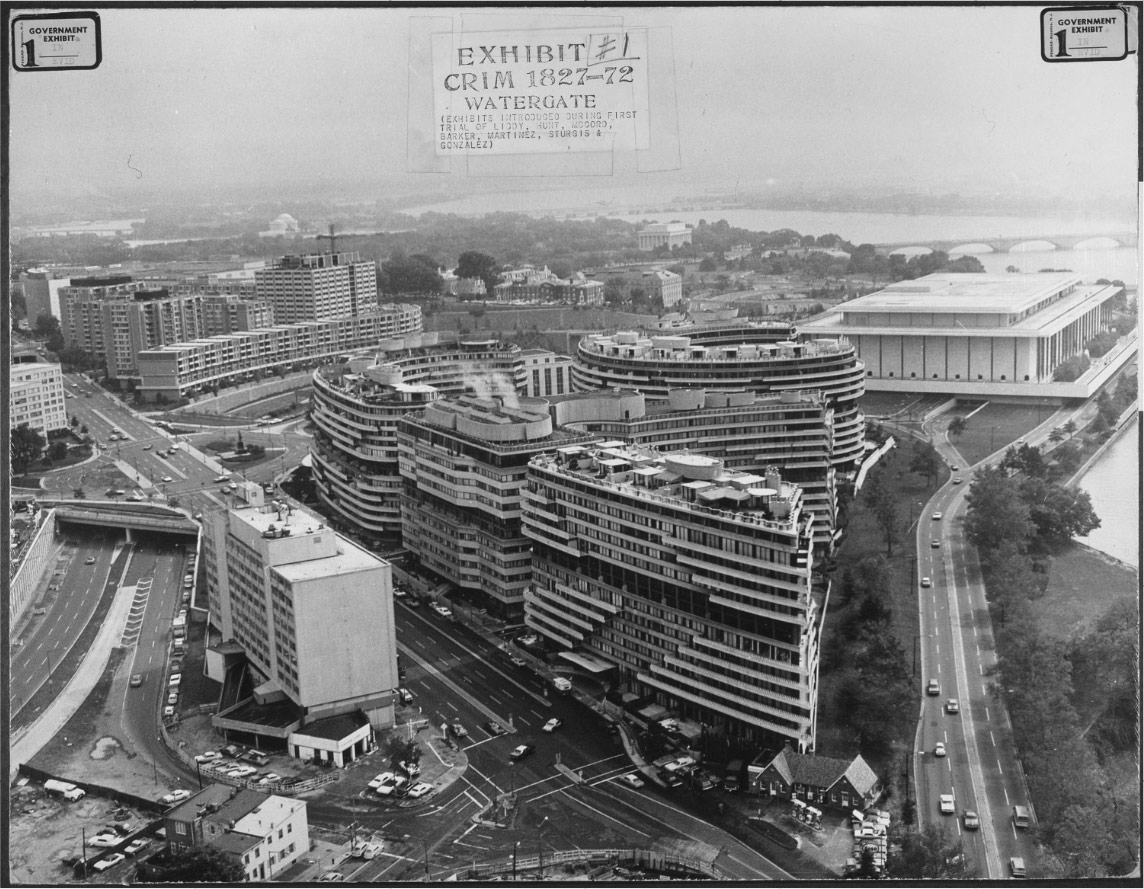

An aerial view of the Watergate Building in Washington, D.C., which housed in 1972 the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee.

The first installment was published online this week in recognition of Saturday’s 45th anniversary of the break-in, and the final piece will run just before the 43rd anniversary of President Richard Nixon’s resignation on Aug. 8, 1974.

“Given the fact that those two anniversaries are about seven weeks apart, we thought we’d do series that spanned that time, releasing one every other week between now and August,” said Tom van der Voort, the Miller Center’s media strategist.

Part one, “Watergate: The Break-in,” focuses on the night of the crime and its immediate aftermath. Like the installments that will follow it, the first features a video interview with the Miller Center’s resident expert on the Nixon tapes, research specialist Ken Hughes.

In his first interview with van der Voort, Hughes explains the nation’s confused and somewhat ambivalent reaction to the early reports of Watergate.

“At first it was a very strange, kind of ‘man bites dog’-type story because people didn’t know what [the burglars] were up to, and it soon became clear that they were connected to the president’s reelection campaign,” he said.

Despite the seemingly baffling connections between the burglary and Nixon’s reelection campaign, there was not any major fallout from Watergate during the 1972 election. People remained largely uninterested, despite the best efforts of Democratic nominee George McGovern to make it a campaign issue.

“In retrospect, that seems strange, but the way it broke at the time it seemed like – and it was – something that happened at a lower level in the campaign,” Hughes said. “There still isn’t any evidence that Richard Nixon had foreknowledge that they were going to break into the Democratic National Committee headquarters, and that makes sense because it was not exactly a rich target for political intel.”

At first, Nixon himself even saw the event as a non-issue. The Miller Center piece includes an excerpt from a recorded conversation between Nixon and his special counsel Charles Colson, who both dismiss the break-in as something that will drop out of the news quickly. When Colson agrees with the president that the whole episode will soon be forgotten, Nixon replies, “Oh, sure, you know, who the hell’s going to keep it alive?”

Future editions of the series will explore how Nixon and his staff ultimately kept the story alive. Part two will dive into the cover-up, the hearings and the investigation; part three will take a closer look at Nixon as a person and as a cultural figure; and part four will focus on Nixon’s resignation and its repercussions.

Like the first edition, each piece will feature a conversation with Hughes, as well as key audio files from the center’s repository of Nixon recordings.

Readers can view part one and each subsequent installment on the Miller Center’s website.

Media Contact

Article Information

June 15, 2017

/content/watergate-miller-center-revisits-infamous-cover-worse-crime