In many ways, the University of Virginia Democracy Initiative’s Memory Project is a continuation of conversations that have been happening for years at UVA, in Charlottesville and beyond – conversations about how we remember history and how memory shapes and reshapes our public spaces.

Memory Project director Jalane Schmidt is well-versed in such conversations. An associate professor of religious studies, Schmidt teaches courses on race, religion and social change and plans and leads public history events in Charlottesville focused on Civil War memory, Jim Crow segregation and local African American history. She was active in meetings of Charlottesville’s Blue Ribbon Commission on Race, Memorials and Public Spaces, established by the city in 2016 to address concerns about Confederate statues in the city, and she co-founded the Monumental Justice Virginia Campaign, which in 2020 successfully lobbied the Virginia General Assembly to overturn a century-old state law that had prohibited localities from removing Confederate statues – a law that the Virginia Supreme Court earlier this month ruled did not apply to Charlottesville’s statues.

On Wednesday, Schmidt and the Memory Project, which was recently relaunched with a focus on local and regional history, will host a virtual talk, “Memorializing Racial Trauma: What Americans Can Learn from the Germans,” with philosopher and author Susan Neiman and Washington Post columnist Michele Norris. The talk will air from 2 to 3:15 p.m.; you can register here.

We spoke to Schmidt beforehand about her hopes and goals for the Memory Project, ranging from supporting local commemorative activities, guiding educational visits to sites of memory, initiatives teaching more Black history in K-12 schools to a documentary film and events like Wednesday’s talk.

Q. How would you describe the focus of the Memory Project?

A. Broadly, the project aims to study how memory is produced and reproduced. More specifically, it is going to be really focused on community outreach and involvement. I especially want to support projects that are already in process in Charlottesville and in other regional cities, such as Richmond or Greensboro, North Carolina.

Associate professor of religious studies Jalane Schmidt directs the Memory Project and teaches courses on race, religion and social change. (Photo by Marley Nichelle)

We don’t want the work to be only theoretical; we want to participate in and catalyze memory work in these communities by providing support for different educational initiatives, media production, the arts, public history and commemorative events. This will be applied scholarship, very forward-facing and open to the public.

Q. What are some projects you are looking forward to working on?

A. There will be courses, curricula, public-facing events and many community-based projects. The 2016 report from the Blue Ribbon Commission is a helpful guide in many ways, and two of The Memory Project’s Advisory Board members, Andrea Douglas and Frank Dukes, were members of that commission. The final report already articulates what people want with respect to racial inclusion in Charlottesville, and that conversation is informing our work.

Votes about Confederate statues have sucked up so much airtime, but there are a lot of other initiatives in that report that have been endorsed by the Charlottesville City Council, such as projects adding more local Black history to school curriculums. In support of that, the Memory Project is sponsoring a local children’s literature author, Marc Boston, who is working on books about local history figures and African American history. We are going to publish those books and donate them to schools.

I am also working with Andrea Douglas on professional development opportunities for teachers, who have told us that they are eager to teach more local Black history, but that they lack materials on figures like Isabella Gibbons. That is a gap we can fill.

[Gibbons and her husband, William, were enslaved by University professors and became a teacher and a minister, respectively, after emancipation. She is honored on UVA’s new Memorial to Enslaved Laborers.]

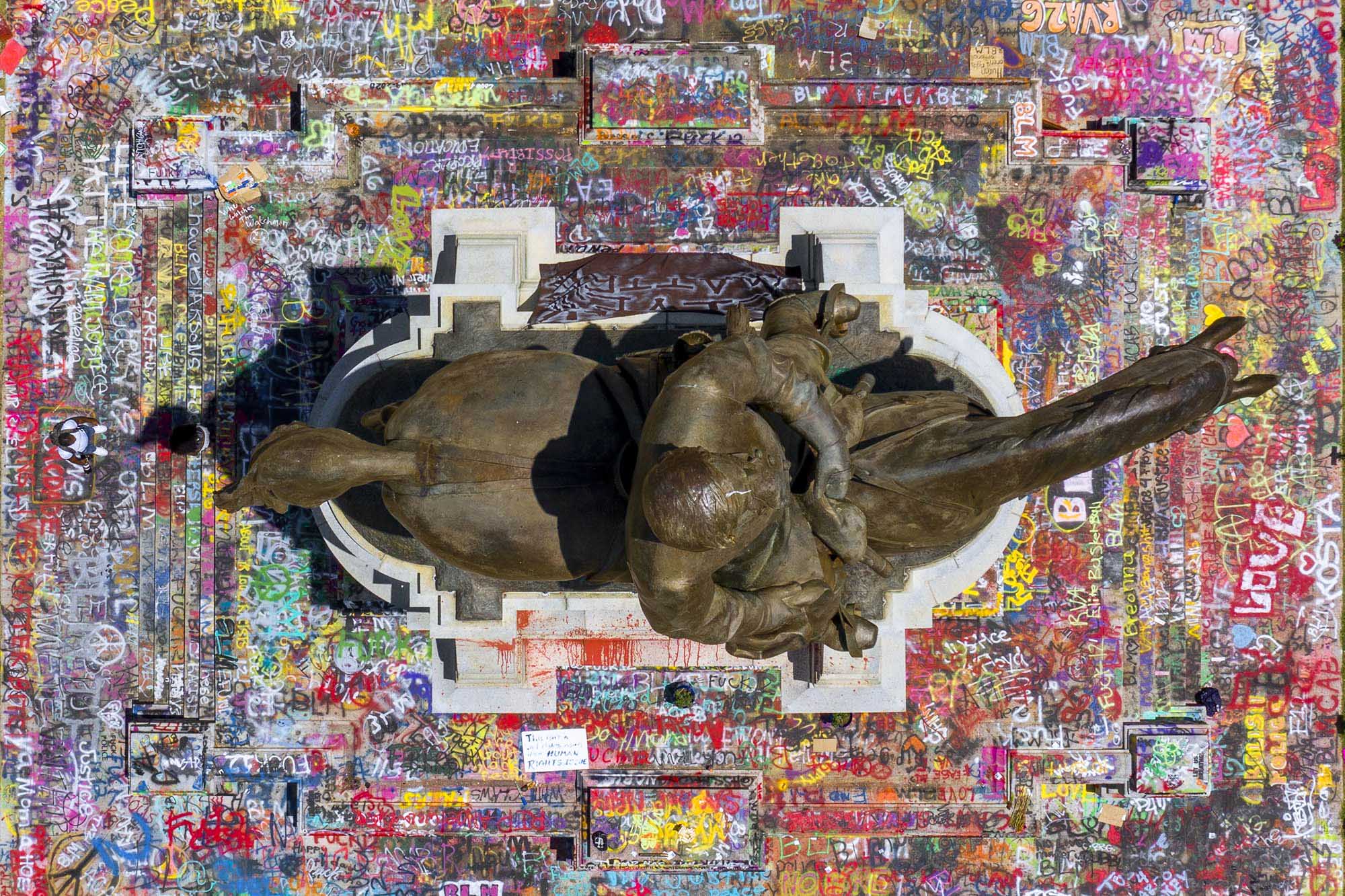

Another project in production is a documentary film about local monuments, including the statues of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson downtown and the George Rogers Clark and Lewis and Clark statues. The documentary will look at the history of these statues and the circumstances in which they were erected, what was said and by whom. It is important to remember that monuments like these are not history, they are memory projects spurred by those who had the power to erect public monuments. They do not always correspond to history.