For the record, Kevin Driscoll hasn’t recently started his day dunking his face in ice water and rubbing a banana peel on his skin.

Just because the University of Virginia media studies professor is an avid social media researcher doesn’t mean he always participates in the latest internet trends.

“I haven’t been personally influenced in that sense,” Driscoll said with a laugh. “I don’t think any video on Instagram will get me up at 3 a.m.”

Fitness influencer Ashton Hall’s facial plunge and fruit-related antics are just a few of the quirks featured in his 2-minute, 14-second “morning routine” video that’s racked up more than 9 million views on X and has received more than 3 million likes on Instagram.

[Sound of hands rubbing together]

[Sound of tape being peeled off]

[Sound of drawer opening]

[Sound of man brushing teeth]

[Sound of water being poured into glass]

[Sound of water being sloshed in mouth]

[Sound of shaving cream being sprayed into hand]

[Sound of razor]

[Sound of door sliding open]

[Sound of man performing push-ups]

[Sound of glass bottle breaking]

[Sound of page turning]

[Sound of writing on notepad]

Speaker 1: Preaching about the arrival of price!

[Sound of ice being poured into a bowl]

[Sound of lemon being squeezed]

[Sound of man’s face being plunged into bowl of ice water]

[Sound of man adjusting his shorts]

Ashton Hall: Thank you.

[Sound of man slipping on tank top]

[Sound of man slipping on sandals]

[Sound of bag being zipped open]

[Sound of bag being zipped closed]

[Sound of door opening]

[Sound of elevator button being pressed]

Elevator voice: Going up

[Sound of elevator door closing]

[Sound of elevator door opening]

[Sound of door opening]

[Sound of feet walking]

[Sound of bag being placed on bench]

[Sound of steam room door opening]

[Sound of steam room door closing]

[Sound of man taking deep breath]

[Sound of man putting on pants and shoes]

[Sound of elevator door opening]

Elevator voice: Going up

[Sound of car driving]

[Sound of man working out]

Ashton Hall: 3, 2, 1

[Sound of man sprinting]

Speaker 2: It’s good to meet you, Ashton.

Speaker 3: That’s crazy.

[Sound of man catching water bottle]

[Sound of car door opening and closing]

[Sound of shower]

[Sound of banana peeling]

[Sound of water running]

[Sound of food being made]

Ashton Hall: Thank you.

[Sound of man swiping on his phone]

[Sound of ice water bowl being slid in]

Ashton Hall: Thank you.

[Sound of man plunging his face in ice water]

Ashton Hall: You’ve made your first 10,000 – congratulations. We got to do at least 20, bro.

The post’s widespread reach and various adaptations have unequivocally helped it go viral. It got us thinking – what does “go viral” actually mean?

A short video posted in October from UVA’s Instagram account – of three students jumping in the pool at the Aquatic and Fitness Center because they refused to call Grounds “campus” – has reached 2.6 million views, making it the most viewed post across any of the University’s social platforms. But did it “go viral”?

[♪ “That Should Be Me” by Justin Beiber plays. ♪]

Now if you're tryna break my heart, it's working because you know that

That should be me holding your hand

“Going viral is more of a feeling than a number,” Driscoll, the author of “The Modem World: A Prehistory of Social Media,” said. “The mathematical vocabulary is limited because it doesn’t get at the feeling, particularly for someone who made the video or post.

“That person can feel their post going viral because they’re getting all these responses and reposts and it’s happening all at once. There’s not a single number that signifies virality for everybody.”

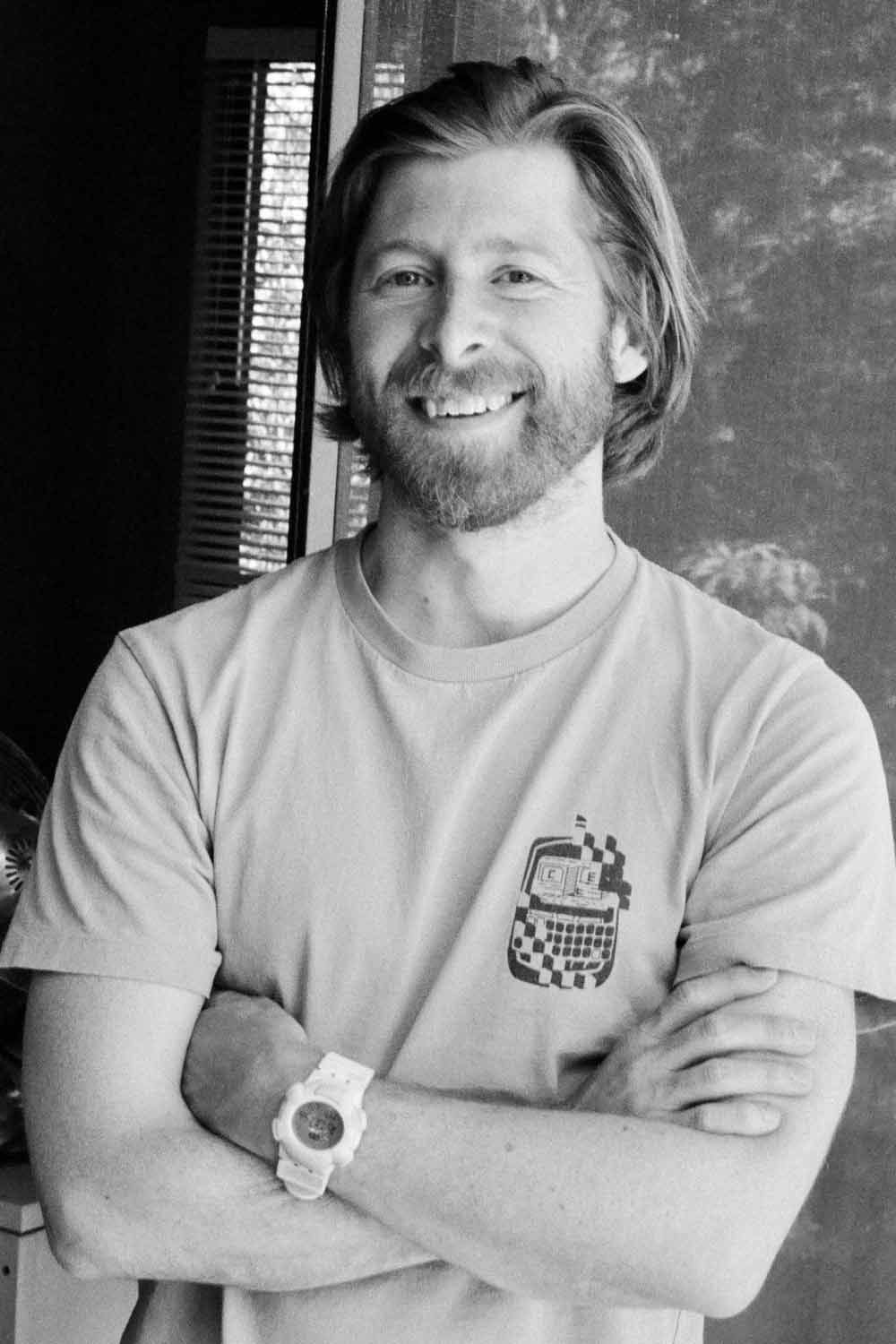

Kevin Driscoll, an associate professor and the associate chair of UVA’s Department of Media Studies, specializes in technology, culture and communication. (Contributed photo)

Some media and culture scholars push back on using the term “viral” in this context, Driscoll said, because of its medical connotation.

“It suggests that we’re passive vectors,” he said, “like this thing hit us and we were compelled to pass it on in the way you would if you had this flu or a cold.

“You don’t choose to spread the cold. But when you’re passing on a meme on the internet, you’re actively choosing to pass it on.”

A virus, though, mutates and evolves, just as Hall’s morning routine post has spread to a range of audiences.

“Different readers have very different ideas of what it’s all about,” Driscoll said. “For some, it’s just a quirky guy doing some weird thing. For others, it’s aspirational and contributes to this culture that many young men are wrapped up in, the grind-set mentality where everyone is a potential rival to you.

“There’s the economic component to it, where people are talking about the different brands that appear in this video. There’s also the representation of masculinity and the performance of Blackness in the video.

“In theoretical terms, it’s an example of polysemy. Just as different readers get different messages from watching the video, they also have different reasons for sharing, commenting, scrutinizing and riffing on it.”

Because of its vague definition, there’s no single post experts claim as the first to “go viral.” Driscoll, though, says the roots of this phenomenon date to the 1990s when chain emails trended.