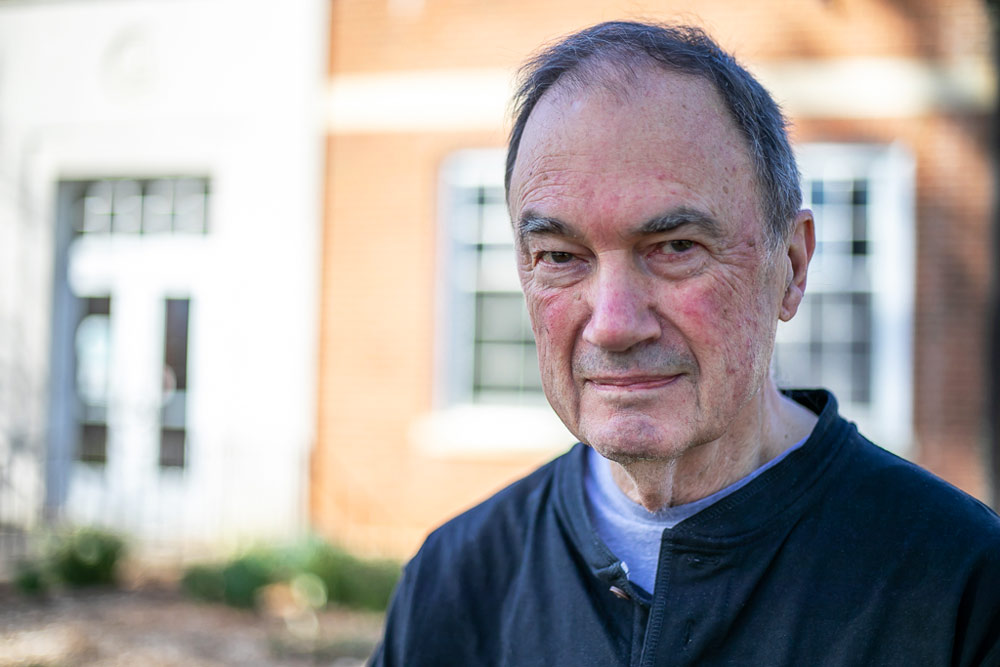

“It has been difficult to see, so we weren’t sure, but it turns out that the amount of power it’s putting out is really pretty small,” Chevalier said. “This one turns out to be quite faint compared to the observed pulsar population. We’d like to understand better what kind of neutron stars form from what kind of a star that becomes a supernova.”

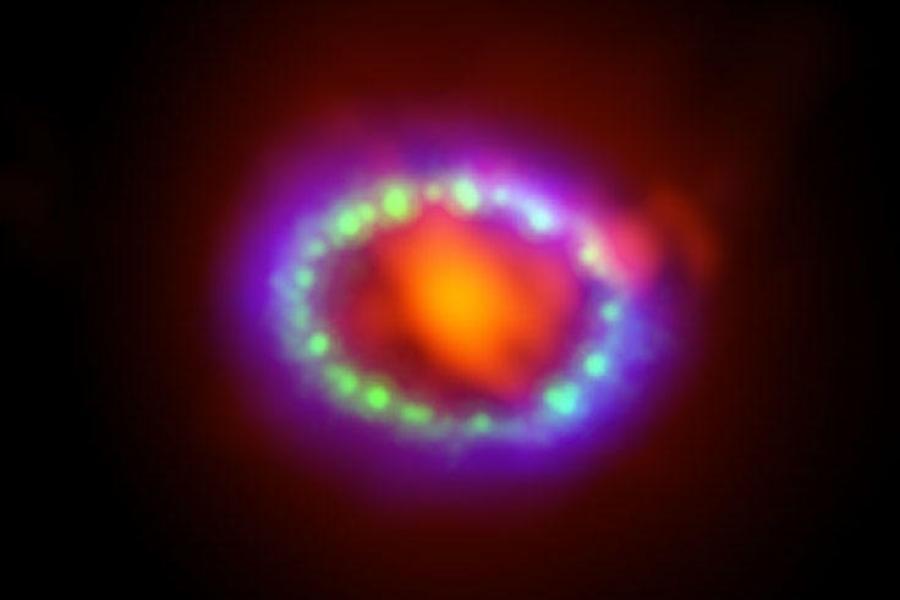

Investigators said the light and radiation measured by the James Webb Space Telescope and other monitoring devices likely come from a once-hot neutron star that’s cooling off or from a pulsar wind nebula, created by a spinning neutron star dragging charged particles in its wake.

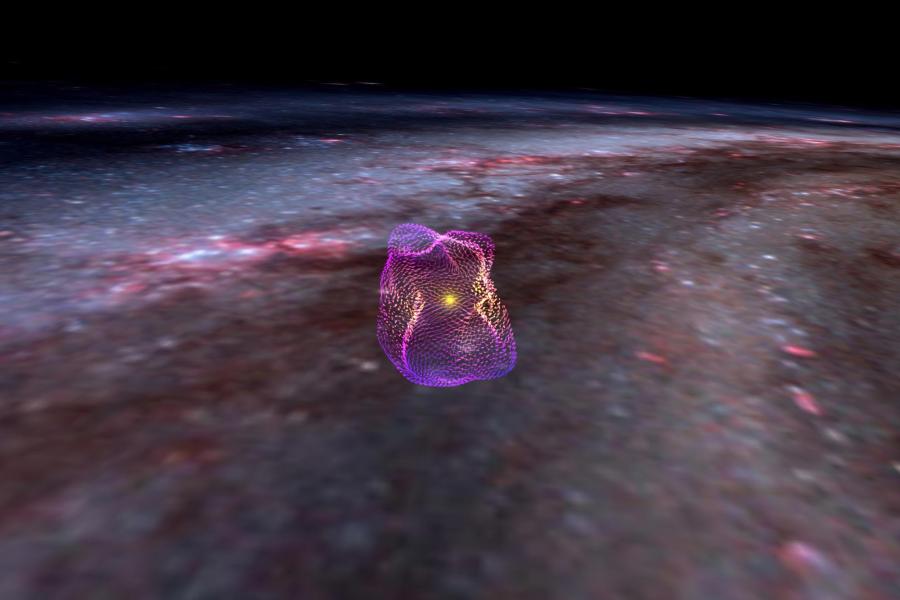

Because the neutron star is young, scientists are watching to see if the star gains momentum or increases its magnetic field as it ages.

“We conclude that the [observations] can be explained by either the cooling neutron star or pulsar wind nebula models, which both require the presence of a neutron star,” the researchers stated in the paper. “A combination of the models is also possible, [but] for the expected parameters, the pulsar wind nebula shock model is less likely.”

Having the Webb Telescope and a known supernova that can be monitored from the time it went off is helping astronomers better understand the impacts of exploding stars. It’s as if they have their own cosmic laboratory for exploration.

“It’s really dependent on having the Webb out there to be able to get the spatial resolution so you can see it – it’s just a little dot near the center,” Chevalier said. “It’s giving us good information about where [the neutron star] is and also how the material is moving along the line of sight.”

Watching the birth and growth of a neutron star is exciting for astronomers, but earthlings need not worry about any nearby stars going supernova, Chevalier said.

“There’s nothing very close to us that’s going to explode, and most of the massive star supernovae we see are from red supergiant stars, like Betelgeuse,” Chevalier said, noting that Betelgeuse was a big topic a few years ago when it began dimming and brightening again.

“Even at 700 light-years, it’s far enough away that it really wouldn’t harm us on Earth,” he said.