His team is poring over infrared-light images from the telescope and other data from the extreme environment, captured during the September observation window.

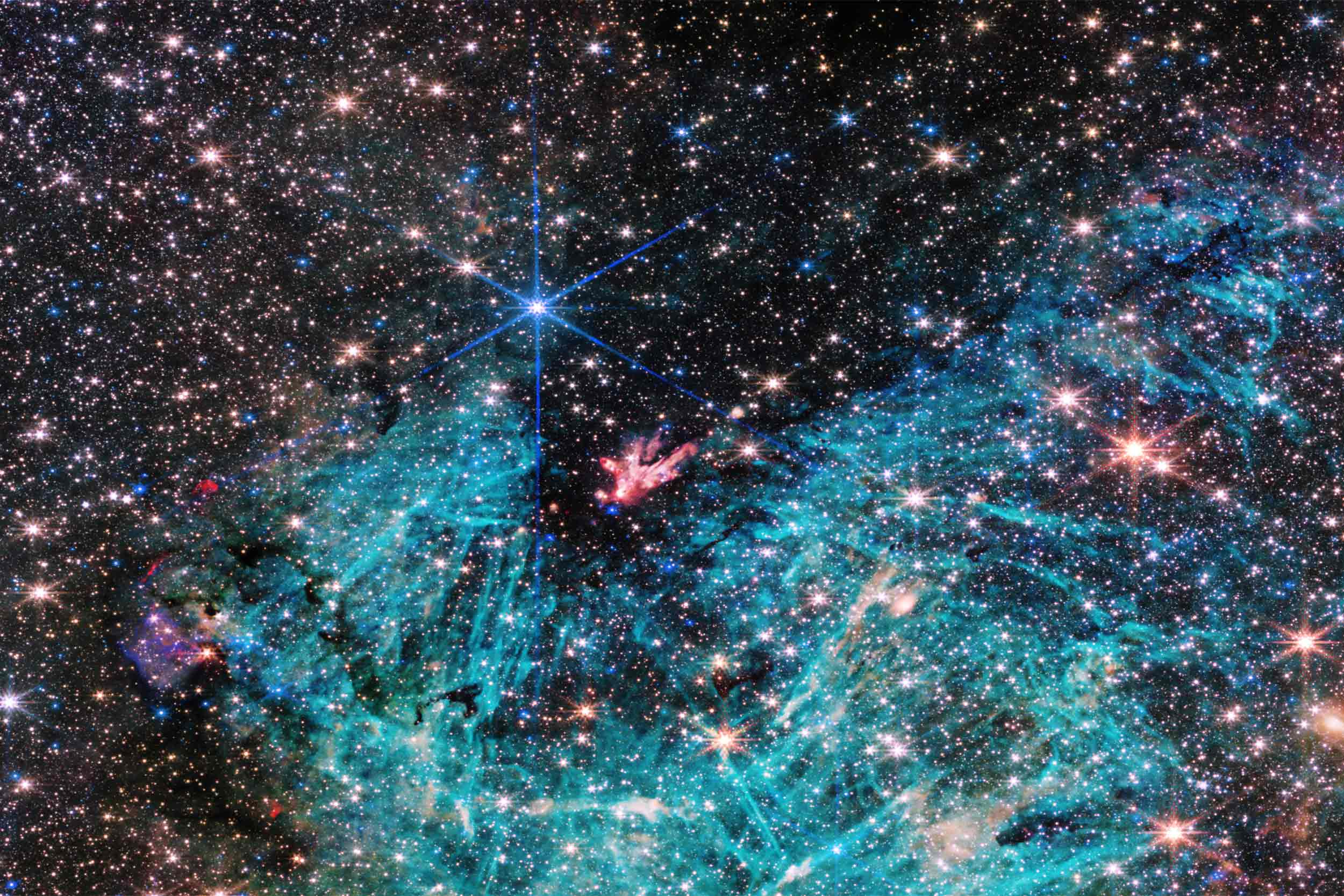

“There’s never been any infrared data on this region with the level of resolution and sensitivity we get with Webb, so we are seeing lots of features here for the first time,” Crowe said.

Crowe, who is majoring in astrophysics and history, was able to earn coveted time on the telescope as part of Webb’s General Observer program. He’s believed to be the first undergraduate student to lead research through the program. “The idea of leading a James Webb proposal as an undergraduate student seemed totally absurd, at least in my head,” said Crowe, who attends UVA on a full-tuition University Achievement Award as an Echols and Robert Kent Gooch Scholar.

But the more he consulted with professional astronomers, the more it seemed possible. He crafted the proposal in conjunction with Jonathan Tan, his Department of Astronomy adviser; UVA postdoctoral researcher Yichen Zhang; and Rubén Fedriani, a postdoctoral researcher at Spain’s Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía.

Crowe now oversees an international research team featuring 13 astronomers from observatories and universities in Spain, Sweden and Japan, as well as UVA and the University of Texas.

He remembers attending the UVA-North Carolina State University football game on Sept. 22 with his girlfriend, looking up at the sky from his seat in Scott Stadium and thinking, “Well, there should be a big telescope pointed at my region right now, taking data, assuming everything goes right.”

At about 10 p.m., Crowe started receiving emails from NASA confirming the capture of imaging data that allows the team to measure how bright each budding star is at different wavelengths.

Their work also includes zooming in on one particularly massive star in the Sagittarius C molecular cloud, designated as “G359.44-0.102.”

In addition, the telescope images reveal dusty infrared-dark clouds of interstellar gas that are the sites of future star formation, and a mist of ionized hydrogen excited by radiation from massive stars.

Collectively, the research may soon offer lessons on the flows of matter and energy that control how galaxies evolve.

The team plans on presenting its initial scientific results in January at the American Astronomical Society conference in New Orleans.

“The galactic center is the most extreme environment in our Milky Way galaxy, where current theories of star formation can be put to their most rigorous test,” Tan explained. “It’s great that we’re collecting state-of-the-art data with this fantastic telescope. It’s even more amazing that it’s being led by one of UVA’s best undergrads.”