March 24, 2009 — Since the mid-1970s, federal and state partners have worked to restore the health of the Chesapeake Bay. This has been no easy task; the bay's watershed extends over more than six states and 64,000 square miles, and farming, development, industry and fishing all impact the bay's health.

The University of Virginia is developing an educational tool to model this complex and interdependent system. The U.Va. Bay Game will give students the opportunity to play critical roles in a simulation focused on the real-world goal of saving the Chesapeake Bay.

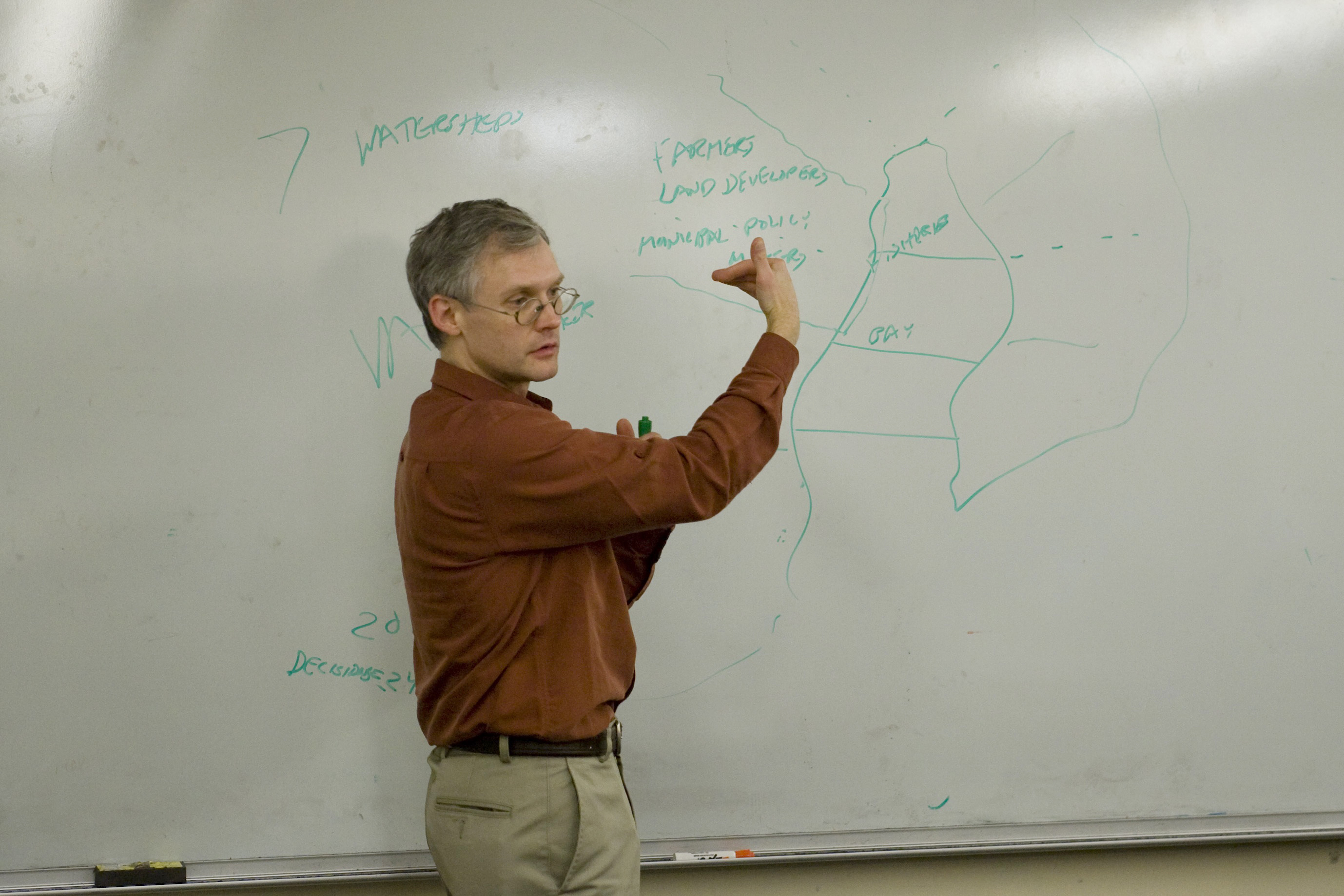

Chris Soderquist, a consultant and expert systems modeler who created a similar game for the Florida Everglades, is designing the game in collaboration with a multidisciplinary U.Va. faculty group and a student advisory team. The game's development is sponsored by the Office of the Vice President for Research.

Faculty and students are scheduled to test the U.Va. Bay Game in early April, and the game will be unveiled to the public at 4 p.m. on April 22 — Earth Day — at the Harrison Institute Auditorium.

Soderquist's Everglades game was intended to teach sustainability concepts to corporate executives. As that game advances, players observe the interactions between the sugar industry, communities and cities in Florida and their impacts on the Everglades system.

In such simulations, players assume different roles in the system. Participants in the Chesapeake Bay Game will assume the responsibilities of key stakeholders such as watermen, farmers, developers and local policymakers. Throughout the course of the game, students will make decisions based on their individual roles, all of which will affect the bay.

A farmer, for example, will monitor details like profits and amount of crop produced per acre and will ultimately decide how much fertilizer to use in a given year or whether to switch to organic farming methods.

As students make choices, they will be able to see also how the overall system is working and they'll have the ability to chat with other students in the game, Soderquist said. "Players learn over the course of a simulation to communicate cross-stakeholder and to make decisions in a collaborative fashion, as opposed to only what's good for them — so they develop a very global perspective on the problems and situation."

The game's evolution has been interdisciplinary, according to Gerard Learmonth, research associate professor in the Department of Systems and Information Engineering and leader in the Bay Game's development. Faculty from U.Va.'s schools of Law, Engineering, Medicine, Commerce and Architecture and the College of Arts and Sciences have contributed data and expertise to the project.

"In designing these games, we always work with subject matter experts who all hold a different piece of the system," Soderquist said. "We get them all into the same room and force them to break down silos and to rise above them in order to get at the big dynamics — to get a complete systems view."

The vision is that the U.Va. Bay Game will eventually serve as a tool for research, education and outreach — not just for students, but for the general public and policymakers as well.

Thomas C. Skalak, vice president for research, said that he expects that the results of the Bay Game simulation will inform future public policies, private investment trends and societal behaviors in ways that enhance human health, economic prosperity and environmental sustainability.

The University of Virginia is developing an educational tool to model this complex and interdependent system. The U.Va. Bay Game will give students the opportunity to play critical roles in a simulation focused on the real-world goal of saving the Chesapeake Bay.

Chris Soderquist, a consultant and expert systems modeler who created a similar game for the Florida Everglades, is designing the game in collaboration with a multidisciplinary U.Va. faculty group and a student advisory team. The game's development is sponsored by the Office of the Vice President for Research.

Faculty and students are scheduled to test the U.Va. Bay Game in early April, and the game will be unveiled to the public at 4 p.m. on April 22 — Earth Day — at the Harrison Institute Auditorium.

Soderquist's Everglades game was intended to teach sustainability concepts to corporate executives. As that game advances, players observe the interactions between the sugar industry, communities and cities in Florida and their impacts on the Everglades system.

In such simulations, players assume different roles in the system. Participants in the Chesapeake Bay Game will assume the responsibilities of key stakeholders such as watermen, farmers, developers and local policymakers. Throughout the course of the game, students will make decisions based on their individual roles, all of which will affect the bay.

A farmer, for example, will monitor details like profits and amount of crop produced per acre and will ultimately decide how much fertilizer to use in a given year or whether to switch to organic farming methods.

As students make choices, they will be able to see also how the overall system is working and they'll have the ability to chat with other students in the game, Soderquist said. "Players learn over the course of a simulation to communicate cross-stakeholder and to make decisions in a collaborative fashion, as opposed to only what's good for them — so they develop a very global perspective on the problems and situation."

The game's evolution has been interdisciplinary, according to Gerard Learmonth, research associate professor in the Department of Systems and Information Engineering and leader in the Bay Game's development. Faculty from U.Va.'s schools of Law, Engineering, Medicine, Commerce and Architecture and the College of Arts and Sciences have contributed data and expertise to the project.

"In designing these games, we always work with subject matter experts who all hold a different piece of the system," Soderquist said. "We get them all into the same room and force them to break down silos and to rise above them in order to get at the big dynamics — to get a complete systems view."

The vision is that the U.Va. Bay Game will eventually serve as a tool for research, education and outreach — not just for students, but for the general public and policymakers as well.

Thomas C. Skalak, vice president for research, said that he expects that the results of the Bay Game simulation will inform future public policies, private investment trends and societal behaviors in ways that enhance human health, economic prosperity and environmental sustainability.

— By Melissa Maki

Media Contact

Article Information

March 24, 2009

/content/uva-sustainability-game-focus-saving-chesapeake-bay