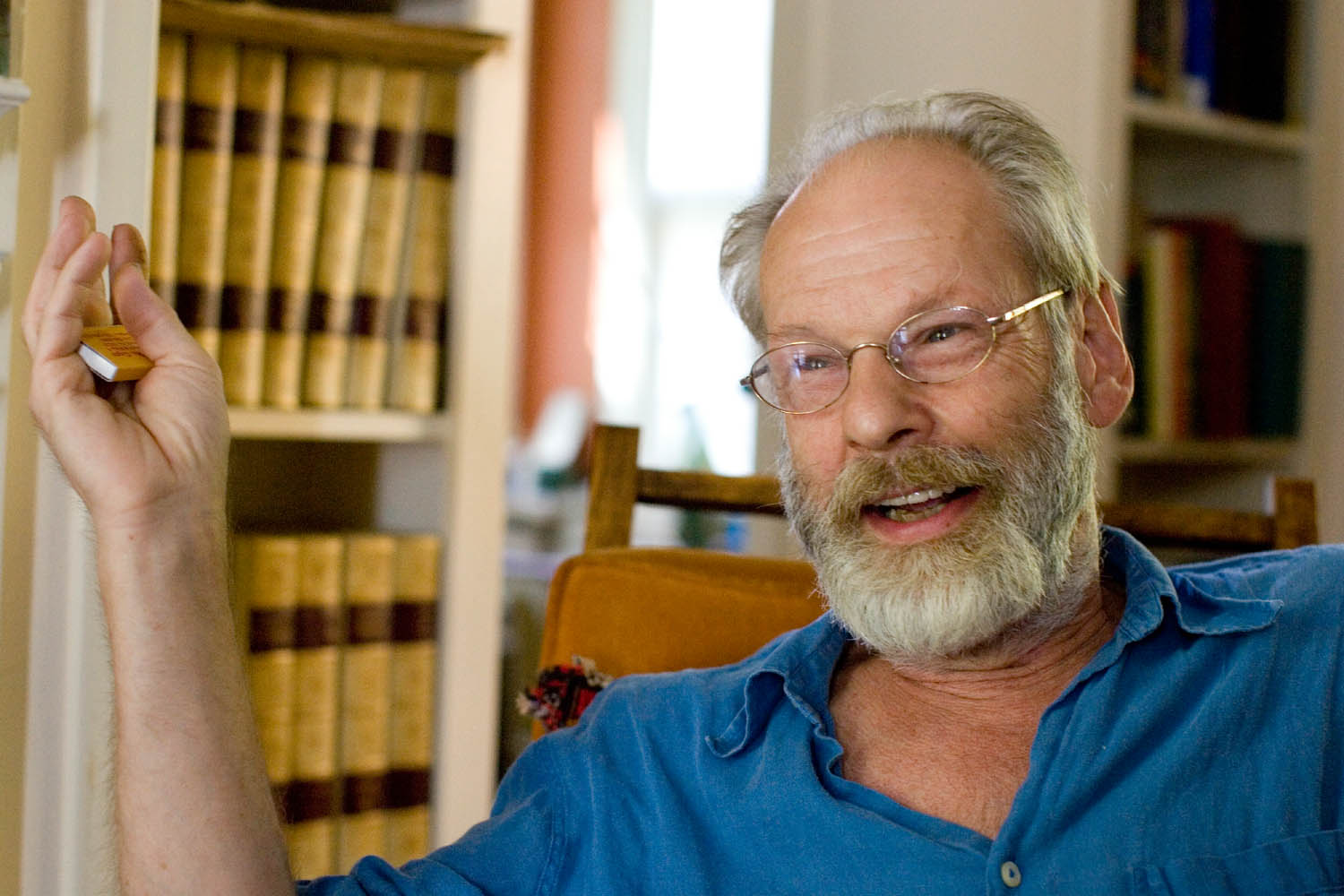

Dec. 10, 2007 — To sit down with noted author and U.Va. English professor John Casey is to hop in the car with the roof down on a sunny day and meander along a winding country road, destination unknown. A gifted raconteur, he weaves together anecdotes from his colorful past that incorporate family, colleagues and former students.

Born in 1939 in Worcester, Mass., into a large Irish-Catholic family, Casey counts among his ancestors two governors (one of whom granted the charter for Harvard College) and one chief justice of Massachusetts. His father Joseph served in the U.S. House of Representatives during the New Deal and worked in the Franklin Roosevelt White House.

“Don’t be a lawyer”

A kid who parlayed a passion for books into a prestigious career as an author, Casey spent his formative years in Washington, D.C., and in Europe. His Uncle Drew, who lived in Paris, persuaded Casey’s parents that their son would do well in the foreign service, and so he attended boarding school in Switzerland to learn French, the language of diplomacy. Casey returned for high school in Washington, attending the elite St. Albans School, where he got caught up in a sense of duty.

“At my school, the fathers of all of my friends were judges, lawyers, politicians or reporters. Washington was a one-industry town. I grew up thinking if you wanted to become a man, you had to perform a public service.”

As a Harvard University undergraduate, Casey studied Russian, planning the diplomatic career to which he felt fated. Instead he became smitten with drama, and for the first time a lifelong stutter was diminished dramatically while performing other people’s words. He eventually ended up at Harvard’s School of Law, where he first got an inkling that he’d missed his calling while taking a writing class taught by author Peter Taylor, who told Casey, “Don’t be a lawyer; be an author.”

Casey passed the D.C. bar, but Taylor’s advice haunted him. So he decided to attend the University of Iowa Writer’s Workshop, where he met some of the premier writers of the day, including John Irving, Gail Godwin and instructor Kurt Vonnegut, who remained a friend until his death in April 2007.

A decade later, Peter Taylor lured Casey to join the U.Va. faculty, where he made his mark professionally and fostered the careers of other writers, including protégé and godson Breece D’J Pancake, whose shocking 1979 suicide devastated Casey during a year of troubles in which his first marriage ended and his father died. He retreated to New England with a Guggenheim Fellowship and a bad case of writer’s block.

The novel

Casey began work on “Spartina,” which would take him 10 years to finish. The novel tells the story of Dick Pierce, a brooding, bitter Rhode Island fisherman who struggles financially and dreams of completing the construction of his boat, Spartina, to make more money and provide a better life for his family. Against this backdrop of frustration, Pierce begins an affair with a younger neighbor whose openness forces him to confront himself in unexpected ways. A New York Times review wrote that the book’s “fearless romantic insistence on lyric,” “mythic symbolism,” and “relentless salt-smack clarity of realistic detail make [the book] just possibly the best American novel about going fishing since ‘The Old Man and the Sea,’ maybe even '’Moby Dick.’”

The honors for “Spartina” cascaded in: Casey received the National Book Award, a prestigious Straus Living Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and then a residency at the American Academy in Rome. There, he met Linda Ferri, whose book he eventually translated into English.

“My brother’s publishing house had just bought the Italian rights to 'Spartina,'" Ferri recalled. "Late one rainy afternoon somebody rang the door of his office. When he opened the door, John appeared, smiling though completely wet, and said, ‘Hello, I’m John Casey. I know you bought my novel, and I wanted to meet you.’

"I don’t know of any Italian or European writer of big success who would do something like that — a way of being young that I am sure he will never lose. ”

A teacher of uncommon generosity

Throughout his career, Casey has sought out new talent for the Master of Fine Arts program in creative writing. He is also known for going out of his way to help his students. English department colleague Deborah Eisenberg said, “John is such a strong presence that you tend to think of this big persona, like he’s the Errol Flynn of letters, but you’re not aware of much he does for other people and his kindness in regard to reading their work, helping with it, appreciating it. He is spectacularly generous.”

Casey’s generosity extends to reading manuscripts, helping students find agents and editors, "blurbing" former student’s books and nurturing raw talent.

“I am most proud of sniffing out talent,” Casey said. “It’s like the dogs and pigs who find truffles. You’ve got to get that little whiff. We’ve had great success with that here.”

Another department colleague, Christopher Tilghman, said that Casey deserves a lot of credit for where the U.Va. creative writing program stands today. “John’s been here since about the mid-'70s, and he’s been the one constant force on the fiction side of our MFA graduate program. I think the high ranking and the high regard that people hold our program in nationally is really a credit to the person who’s been here the longest.”

The writing process and rowing

Casey continues to write his books in long-hand, and recently completed the yet-unnamed sequel to “Spartina.” “I write very slowly, and I have to have a goal. Sometimes it’s very hard to get there, and when I do, it’s sort of like a hoop you burst through,” he said. He writes in a spartan shed behind his home. “My shed is a shambles, pieces of paper, pipe cleaners everywhere. I’m up at the crack of dawn — 10 a.m.,” he said, tongue-in-cheek. “Writing is a little bit auto-hypnosis: once I go down there, clean the pipe, light it and then start thinking. Then words occur, very slowly, and there’s a point where it’s over, that’s it, you’re not in the zone any more. You might as well go row.”

Among Casey’s lifelong passions is rowing, which he did as a child and took up again at mid-life, becoming the faculty advisor for the U.Va. women’s rowing team. Much of his free time is spent paddling up and down the East Coast. “My brother-in-law and I decided we could canoe from our mother-in-law’s place in Pennsylvania all the way to my father’s house near Annapolis in six days. So we’re going to do it.”

Casey, who is married to noted artist Rosamund Casey and father to four daughters — two of whom write professionally — continues to write, teach and advocate for his students. He is determined to lobby for more funding for the Hoyns Fellowship to remain competitive with other MFA programs and bring in the best candidates to U.Va. He also plans to continue writing as long as he can.

“I suppose someday someone will come along and say, ‘Sorry, kid, you’ve lost it.’ That’s up there on the par with all the daughters leaving home — what a vacuum! I would rather be without writing than without children, but it’s a close-run race. I think I’d still write letters at least!”

— Written by Jenny Gardiner

Born in 1939 in Worcester, Mass., into a large Irish-Catholic family, Casey counts among his ancestors two governors (one of whom granted the charter for Harvard College) and one chief justice of Massachusetts. His father Joseph served in the U.S. House of Representatives during the New Deal and worked in the Franklin Roosevelt White House.

“Don’t be a lawyer”

A kid who parlayed a passion for books into a prestigious career as an author, Casey spent his formative years in Washington, D.C., and in Europe. His Uncle Drew, who lived in Paris, persuaded Casey’s parents that their son would do well in the foreign service, and so he attended boarding school in Switzerland to learn French, the language of diplomacy. Casey returned for high school in Washington, attending the elite St. Albans School, where he got caught up in a sense of duty.

“At my school, the fathers of all of my friends were judges, lawyers, politicians or reporters. Washington was a one-industry town. I grew up thinking if you wanted to become a man, you had to perform a public service.”

As a Harvard University undergraduate, Casey studied Russian, planning the diplomatic career to which he felt fated. Instead he became smitten with drama, and for the first time a lifelong stutter was diminished dramatically while performing other people’s words. He eventually ended up at Harvard’s School of Law, where he first got an inkling that he’d missed his calling while taking a writing class taught by author Peter Taylor, who told Casey, “Don’t be a lawyer; be an author.”

Casey passed the D.C. bar, but Taylor’s advice haunted him. So he decided to attend the University of Iowa Writer’s Workshop, where he met some of the premier writers of the day, including John Irving, Gail Godwin and instructor Kurt Vonnegut, who remained a friend until his death in April 2007.

A decade later, Peter Taylor lured Casey to join the U.Va. faculty, where he made his mark professionally and fostered the careers of other writers, including protégé and godson Breece D’J Pancake, whose shocking 1979 suicide devastated Casey during a year of troubles in which his first marriage ended and his father died. He retreated to New England with a Guggenheim Fellowship and a bad case of writer’s block.

The novel

Casey began work on “Spartina,” which would take him 10 years to finish. The novel tells the story of Dick Pierce, a brooding, bitter Rhode Island fisherman who struggles financially and dreams of completing the construction of his boat, Spartina, to make more money and provide a better life for his family. Against this backdrop of frustration, Pierce begins an affair with a younger neighbor whose openness forces him to confront himself in unexpected ways. A New York Times review wrote that the book’s “fearless romantic insistence on lyric,” “mythic symbolism,” and “relentless salt-smack clarity of realistic detail make [the book] just possibly the best American novel about going fishing since ‘The Old Man and the Sea,’ maybe even '’Moby Dick.’”

The honors for “Spartina” cascaded in: Casey received the National Book Award, a prestigious Straus Living Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and then a residency at the American Academy in Rome. There, he met Linda Ferri, whose book he eventually translated into English.

“My brother’s publishing house had just bought the Italian rights to 'Spartina,'" Ferri recalled. "Late one rainy afternoon somebody rang the door of his office. When he opened the door, John appeared, smiling though completely wet, and said, ‘Hello, I’m John Casey. I know you bought my novel, and I wanted to meet you.’

"I don’t know of any Italian or European writer of big success who would do something like that — a way of being young that I am sure he will never lose. ”

A teacher of uncommon generosity

Throughout his career, Casey has sought out new talent for the Master of Fine Arts program in creative writing. He is also known for going out of his way to help his students. English department colleague Deborah Eisenberg said, “John is such a strong presence that you tend to think of this big persona, like he’s the Errol Flynn of letters, but you’re not aware of much he does for other people and his kindness in regard to reading their work, helping with it, appreciating it. He is spectacularly generous.”

Casey’s generosity extends to reading manuscripts, helping students find agents and editors, "blurbing" former student’s books and nurturing raw talent.

“I am most proud of sniffing out talent,” Casey said. “It’s like the dogs and pigs who find truffles. You’ve got to get that little whiff. We’ve had great success with that here.”

Another department colleague, Christopher Tilghman, said that Casey deserves a lot of credit for where the U.Va. creative writing program stands today. “John’s been here since about the mid-'70s, and he’s been the one constant force on the fiction side of our MFA graduate program. I think the high ranking and the high regard that people hold our program in nationally is really a credit to the person who’s been here the longest.”

The writing process and rowing

Casey continues to write his books in long-hand, and recently completed the yet-unnamed sequel to “Spartina.” “I write very slowly, and I have to have a goal. Sometimes it’s very hard to get there, and when I do, it’s sort of like a hoop you burst through,” he said. He writes in a spartan shed behind his home. “My shed is a shambles, pieces of paper, pipe cleaners everywhere. I’m up at the crack of dawn — 10 a.m.,” he said, tongue-in-cheek. “Writing is a little bit auto-hypnosis: once I go down there, clean the pipe, light it and then start thinking. Then words occur, very slowly, and there’s a point where it’s over, that’s it, you’re not in the zone any more. You might as well go row.”

Among Casey’s lifelong passions is rowing, which he did as a child and took up again at mid-life, becoming the faculty advisor for the U.Va. women’s rowing team. Much of his free time is spent paddling up and down the East Coast. “My brother-in-law and I decided we could canoe from our mother-in-law’s place in Pennsylvania all the way to my father’s house near Annapolis in six days. So we’re going to do it.”

Casey, who is married to noted artist Rosamund Casey and father to four daughters — two of whom write professionally — continues to write, teach and advocate for his students. He is determined to lobby for more funding for the Hoyns Fellowship to remain competitive with other MFA programs and bring in the best candidates to U.Va. He also plans to continue writing as long as he can.

“I suppose someday someone will come along and say, ‘Sorry, kid, you’ve lost it.’ That’s up there on the par with all the daughters leaving home — what a vacuum! I would rather be without writing than without children, but it’s a close-run race. I think I’d still write letters at least!”

— Written by Jenny Gardiner

Media Contact

Article Information

December 10, 2007

/content/uva-profiles-features-award-winning-author-john-casey