Every third Thursday of the month at The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia, a 45-minute discussion is transforming lives.

Launched in September 2010, “Eyes on Art” – designed in partnership with the Central and Western Virginia Chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association – provides quality-of-life experiences for people with Alzheimer’s disease through interaction with the museum’s collection.

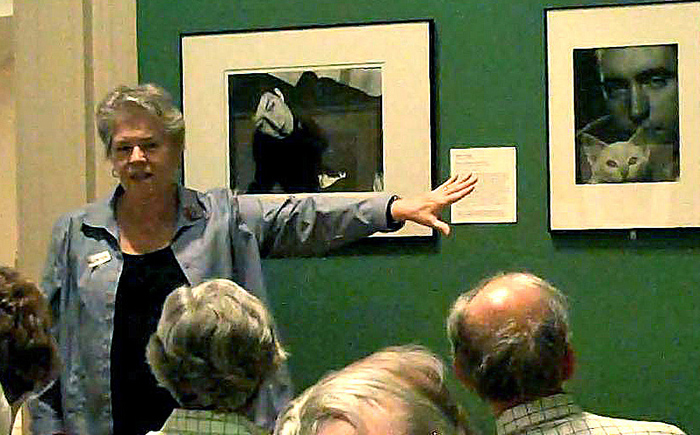

Specially trained docents lead individuals with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers on small-group tours of the museum’s exhibits and engage participants in meaningful discussions about specific works of art.

These tours – more like 45 minutes of conversation – serve those in the early stages of Alzheimer’s, as well as those in the more advanced stages of the disease, who gather at the museum monthly accompanied by their caregivers. Participants in the early-stage groups often participate multiple times, and many have been coming for a couple of years.

In addition, the museum works with residential facilities to offer group tours for individuals with Alzheimer’s who are no longer in the home. Nine different care-giving and assisted-living facilities in the Charlottesville area – including the Colonnades, Rosewood Village, Morningside and The Laurels – bring groups to the museum for art-centered discussions.

The next tour, on Aug. 22, will showcase the museum’s new exhibit on French artist Émilie Charmy.

“I expect the expressiveness of Charmy’s portraits to elicit a lot of conversation from the individuals with Alzheimer’s as well as their caregivers,” said Aimee Hunt, the Fralin Museum’s associate academic curator, who oversees the museum’s growing educational outreach programs.

Each third Thursday of the month the museum usually has about a dozen early-stage participants in Eyes on Art, and Hunt reports some 395 total participants in the program since its inception.

“Eyes on Art” is based on a similar, highly successful program developed by New York’s Museum of Modern Art, dubbed “Meet Me at MoMA.”

“Several years ago, MoMA received a large grant to help other museums across the country start similar programs for people with Alzheimer’s,” Hunt.said. “One of the first museums they helped was the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, which assisted The Fralin in starting our own program.

“One of The Fralin’s advisory board members, Margaret Doyle, works as the director of communications at the Museum of Modern Art, and she was helpful in establishing their program here. Our program was also greatly supported by Jo Rowan, a member of The Fralin’s advisory board and chair of the volunteer board, whose husband suffered from Alzheimer’s before he passed away earlier this year.”

The museum collaborated with the Alzheimer’s Association, Central and Western Virginia Chapter, and works closely with Sharon Celsor-Hughes, the chapter’s creative arts director and a former docent coordinator at U.Va.’s museum.

Through the Alzheimer’s Association’s Arts Fusion program, she develops community partnerships with art organizations to establish programs designed to engage those with Alzheimer’s.

The tours and talks at The Fralin Museum of Art are not fine arts lectures, Celsor-Hughes explained, but are based on the inquiry method, which helps engage the participants, who are often withdrawn, in conversation.

Caregivers typically contact the regional Alzheimer’s Association shortly after there has been a diagnosis, inquiring about support groups and activities. Eyes on Art is central to their support program.

Museum docents like Melinda Hope – who has been a docent at the museum for 29 years and an empathetic guide for Eyes on Art since its inception – receive training from the Alzheimer’s Association staff.

“It takes practice to reach the level of competency required to facilitate these tours,” Celsor-Hughes said. “My time with the docents is focused on providing a basic understanding of how Alzheimer’s affects cognitive abilities and the impact this has on their role as program facilitators.”

Although docents prepare questions to prompt discussion, the conversation usually follows the participants’ lead. Hope’s intent is to make sure that everyone has spoken and has a chance at one-on-one contact.

Hope asks intriguing questions, helping direct people to get answers on their own, and gently moves groups from one work to the next. She works with Celsor-Hughes and the museum’s education department to identify the works of art that will best stimulate memories.

The goal is to choose images that are engaging and uplifting. A frequent reward is seeing the smiles on the participants’ faces when there’s some recognition of an image from the past featured in the artwork.

“I held a tour and discussion last week, and the participants were actively engaged in analyzing the work and the motivations of the artist,” Hunt said. “They were also very opinionated. They had a lot to say about what they liked and didn’t like.”

Celsor-Hughes added, “A caregiver shared with me that the museum program provides a safe environment – one where she and her husband can relax. She said he utilizes a part of his brain that isn’t filled with the stresses of ‘where am I?’ or ‘take me home.’”

Celsor-Hughes said that one caregiver was pleased to learn that The Fralin’s guards, aware of the potential for wandering, would alert them if her husband tried to leave the building unattended. “So you can see that the success of this program is due to the museum’s willingness to embrace the special needs of the group.”

Research has demonstrated that looking at art can have an effect on both those suffering from Alzheimer’s and their caregivers. In 2008, the Museum of Modern Art and the New York University Center of Excellence for Brain Aging and Dementia completed an evaluative study of the Meet Me at MoMA program. Researchers used quantitative and qualitative measures to assess the change in quality of life, mood and level of engagement in activity of people with Alzheimer's and their family members. They found that engaging with art improved the mood of both people with Alzheimer’s and caregivers.

“With Eyes on Art, the caregivers report that they see mood enhancement from the visits,” Hunt said. “The visit enhances the mood beforehand, because they’re anticipating coming to the museum, and it enhances the mood afterward because they got out, were active and enjoyed the experience.”

Hunt recalled a story about a woman who had attended the Eyes on Art program regularly with her husband.

“She said, ‘When we’re at home, I’m his caregiver, but when we come out to the museum, we’re a couple again.’

“This was just incredibly touching, because it speaks to the change in a relationship over time. For her, the program was so meaningful because it allowed her to go back to the time when they were truly a couple.”

Media Contact

Article Information

July 29, 2013

/content/fralin-museum-s-eyes-art-brings-art-people-alzheimer-s