The oldest building on the University of Virginia’s Grounds isn’t the Rotunda, or the Thomas Jefferson-designed Pavilion VII, where the University’s cornerstone was laid.

Instead, a small, white, brick house on Monroe Hill, built circa 1789, predates the University’s buildings by 30 years. It was a law office for James Monroe, the fifth president of the United States, when he owned the land.

Now, a new documentary film-in-progress will tell the story of life at Monroe Hill, focusing on the decade when Monroe owned the property in the late 18th century and touching on the legacy of education and the early students who lived there in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Overshadowed by Jefferson’s Academical Village, the buildings on Monroe Hill hold their own history, begun well before it became the distinctive home of U.Va.’s Brown College today. After Monroe lived there off and on with his wife, Elizabeth, for 10 years, the subsequent owner, John Perry, had the main house renovated in 1814 and gave it a Greek revival façade – unlike Jefferson’s Palladian designs.

The oldest building on Grounds, James Monroe's law office, was built in 1789-90. Photo by Eduardo Montes-Bradley.

U.Va.’s first scholarship students lived in rooms on Monroe Hill connected by two adjacent arcades, opened in 1848 for about 24 students. U.Va. built 12 residence halls on Monroe Hill in 1929, and they were reserved for first-year students until 1952, when the McCormick Road houses opened. The Monroe Hill complex became the first of U.Va.’s three residential colleges in 1986 and was renamed Brown College in 1994.

“James Monroe tried to make Monroe Hill a working farm and planted all kinds of seeds that ended up failing,” Montes-Bradley said – that is, until he joined Thomas Jefferson and James Madison 20 years later. The three men – presidents, friends and founders of the Republic – gathered on the morning of Oct. 6, 1817 to plant the seed of public education by laying the cornerstone for the University of Virginia.

James Monroe, circa 1816 by John Vanderlyn.

Along with Plaskon, principal Melissa Thomas-Hunt, associate professor of business administration at the Darden School of Business, oversees Brown College. Two resident faculty scholars and 40 faculty fellows join about 300 students on a daily basis to share meals, short courses and other activities.

The student-interns are learning through research about James Monroe’s failed attempts to make the property a successful plantation and the events that interrupted his time there, such as the French Revolution. They are also receiving hands-on training in the many parts of film production.

After applying to become interns, most of the cohort of 15 went to work this spring, wearing several hats as needs arose. About half are working this summer, with the others planning to continue when they return to Grounds for the fall semester.

Montes-Bradley said he wants the students to get an idea of what disciplines and skills intersect throughout the filmmaking process, from academic research to scriptwriting to conducting interviews to solving practical details of sound and lighting.

Montes-Bradley recently talked about the film project on WTJU’s “Soundboard” program. He would like the film to “restore to the premises the soul that has been lost,” he said. “From his letters, we can see that Monroe dreamt about this place from overseas.”

With an award for production from the Jefferson Trust, and support from Brown College, the Curry School, Ash Lawn-Highland (Monroe’s more famous home) and the Presidential Precinct, the film has already secured worldwide distribution in the academic market for universities and libraries.

Here is a sneak peek at the production process, what the crew’s been doing and what they’ve found.

Students on Film Crew Bringing ‘the Soul’ of Monroe Hill to Light

From left to right, Caitlin Muir, Daniel Van-Nostrand and Ben Camber began working on the film project this spring. Photo by Eduardo Montes-Bradley.

“When I heard that there was going to be a documentary about Monroe Hill, I knew I wanted to be involved, because I wanted to explore how bringing a film to life can change those involved,” Muir wrote in an email. Due to this experience, she’s considering production as a career. “I knew I wanted to work with Soledad, because she’s had a great deal of experience in the field,” she wrote.

“There are a number of small details that producers have to handle, but it’s all these details and making sure that everything fits together that make me love this job,” she continued. “I’ve been involved every step of the way and I’ve enjoyed getting to work with other students. Plus, the interviewees have all been wonderful.”

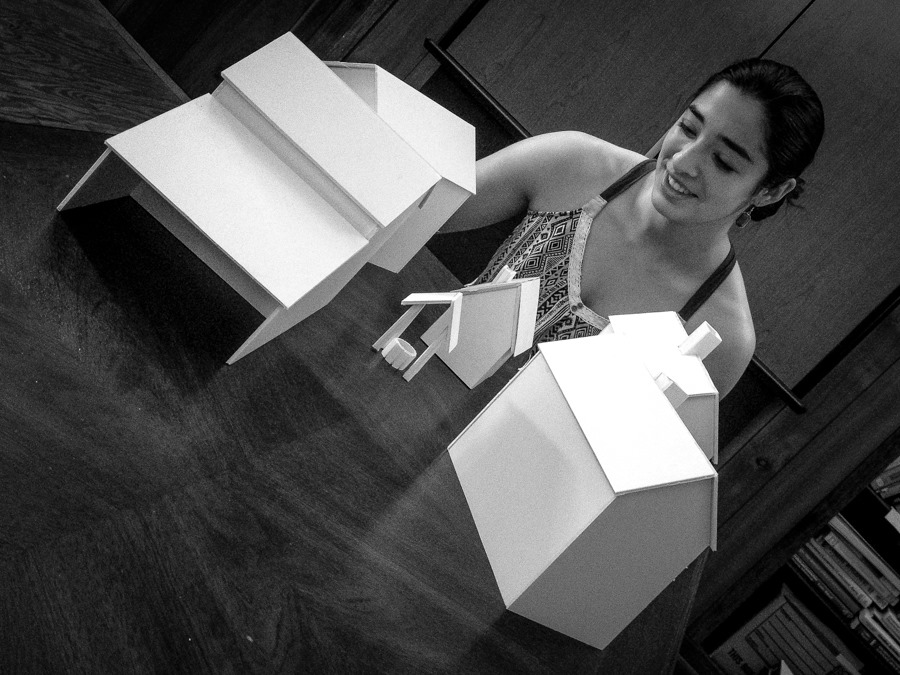

Architecture student Emma Bross made a model of some of the original buildings to help visualize Monroe's farm. Photo by Eduardo Montes-Bradley.

Her experience so far has reminded her of the range of jobs and careers out there, she said. “If you seek the right opportunities or know the right people, you can find a way to apply the skills you’ve learned to a unique, perhaps liberal-arts-type of career.”

Bross will continue to work on the project when she returns to U.Va. in the fall.

Sage Tanguay, left, Will Mullany and Brandon Sangston, standing, take a break from helping with filming at Ash Lawn-Highland. Photo by Eduardo Montes-Bradley.

Mullany said he’s getting more general firsthand exposure to the whole production process than he thought he would. He’s learning how to use the equipment and has helped on several of the photo shoots, even if that means holding a reflective screen to adjust the lighting. “It has made the idea of filmmaking less intimidating and more doable,” he said.

“The crew of student residents from Brown College were outstanding!” Montes-Bradley posted on Facebook along with some photos.

Sangston snapped a photo of Montes-Bradley filming Sara Bon-Harper, executive director of Ash Lawn-Highland, Monroe's later and more famous home not far from Jefferson’s Monticello. Photo by Brandon Sangston.

“I’ve learned a lot about the dynamics and organization of filmmaking,” Sangston said, “but I would say that the most productive experience has been learning how to use the equipment. From the boom mic to lighting to Eduardo’s crazy shoulder-mounted camera rig, we’ve been given the chance to learn it all,” said Sangston, who added he “was ecstatic to learn about the opportunity to work on a professional documentary.”

U.Va.’s First Scholarship Students Lived on Monroe Hill

U.Va.’s first scholarship students lived in the rooms on the two arcades of Monroe Hill, opened in 1848 for 24 students.

Maurie McInnis, a U.Va. professor of American art and material culture who also serves as vice provost for academic affairs, is a 1988 alumna and former Monroe Hill resident. She’s one of a dozen specialists who Montes-Bradley and the students will interview for the film. Among her varied roles on Grounds, McInnis regularly teaches a first-year advising, or COLA, seminar, “Histories and Mysteries of U.Va.”

“The film making project on Monroe Hill is uncovering important information about the role that area played in the University’s history,” she said. “Just next door to the Academical Village, it was originally not part of the University, but as the school grew, it became incorporated into the University proper.

“One of the most interesting details to come to light is the fact that it became the home to some the University’s earliest scholarship students. These students were the Access UVA students of the 19th century: students of academic merit with financial need whose expenses were covered.”

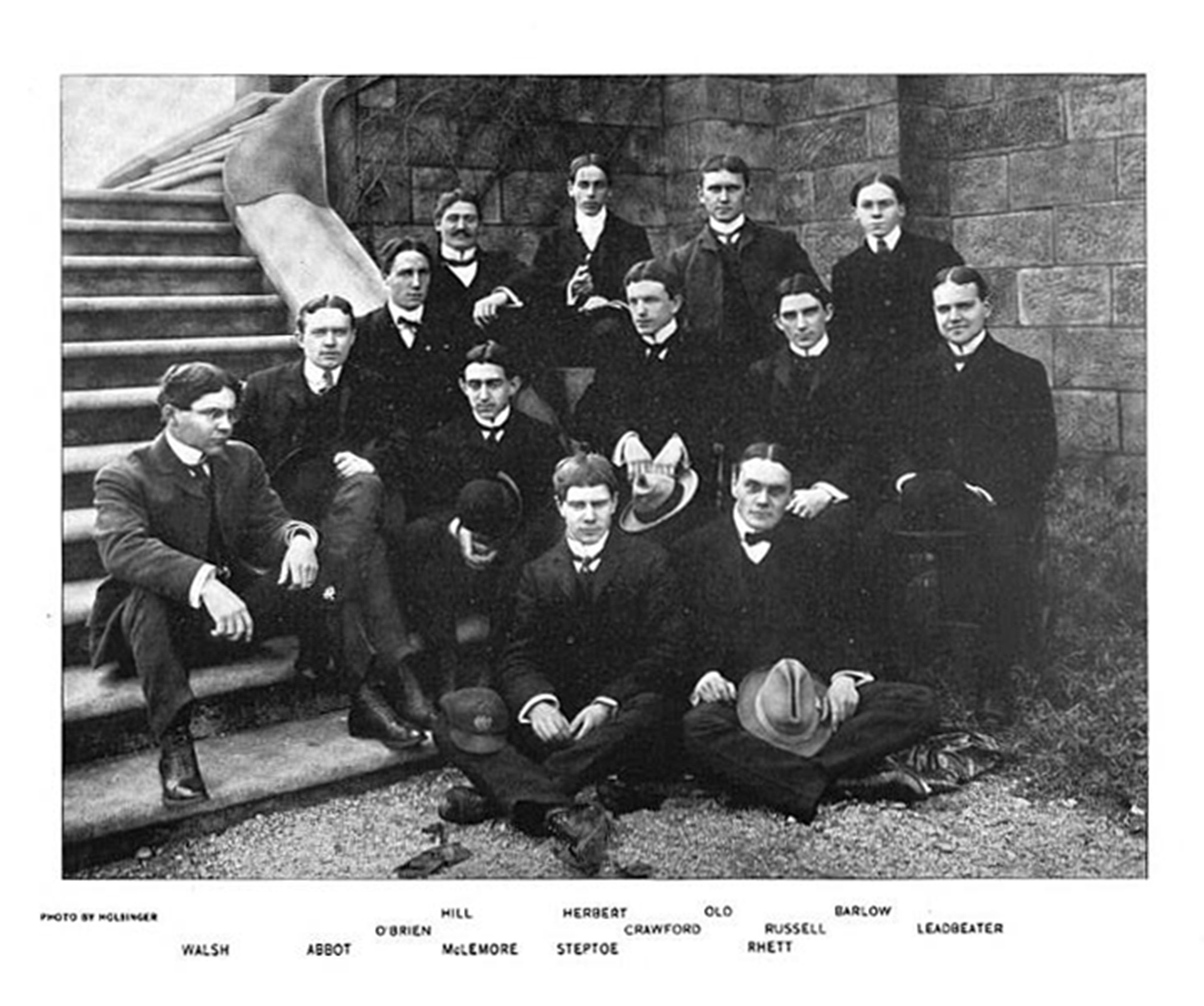

This photo made by Rufus Holsinger in the late 1800s and other old images helped the film crew match some of the names with the faces.

Exploring the history of students who signed their names on the mortar between bricks, Montes-Bradley and students researched “all identifiable signatures,” Montes-Bradley said.

“They reveal the presence of extraordinary individuals, many veterans from the [Spanish-American] War, university presidents, renowned scientists and other fascinating characters,” he said.

Stephen Mazyck O’Brien inscribed his name in 1898, probably a year before he graduated. From Louisville, Kentucky, he’s the third from left in ascending order.

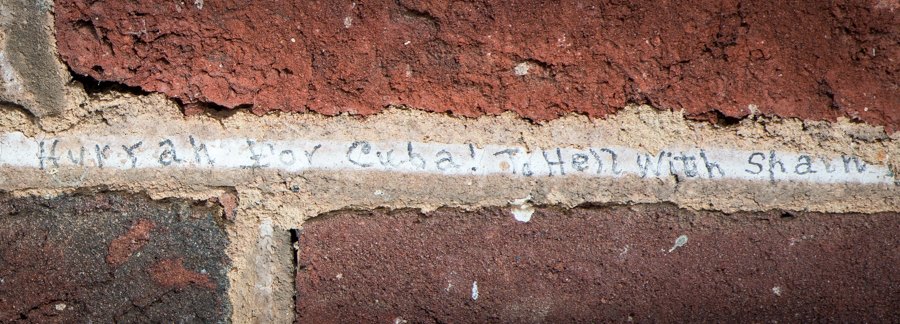

P.C. Massie and J.R. Kean (top) signed their names on the mortar between bricks when they were students at Monroe Hill. Students also left messages about the Spanish-American war (bottom).

Along with P.C. Massie, J.R. Kean, great-grandson of Thomas Jefferson, signed the brick wall when he was a U.Va. student in the 1880s. Jefferson Randolph Kean became a brigadier general in the Spanish-American war and was a colleague of renowned Army doctor Walter Reed.

From his papers at the National Library of Medicine, Kean wrote of U.Va.: “In 1879 I was sent to the University of Va. where being still rather immature I lived the first year in the family of the distinguished dean of the law school, Dr. John B. Minor, a grand old man of forceful and, I thought, rather puritanical turn of mind. I called him cousin, but the relationship was rather a friendship between our families extending through several generations than any actual kinship. During this year one of the law students who called frequently at the house was Woodrow Wilson, afterwards President of the United States. He was a mature man and even at that time much looked up to for his oratorical accomplishments.”

F. P. Venable was an early student who lived at Monroe Hill. He later became the president of the University of North Carolina.

Another name hidden on the mortar between the bricks of the northern wall is that of Francis Preston Venable, class of 1879. Venable became a chemist and educator, and later the ninth president of the University of North Carolina. His father, Charles Scott Venable, was professor of mathematics at U.Va. from 1865 to 1896.

Director of Studies Stephen Plaskon, second from left, and Montes-Bradley, third from left, invited U.Va. Associate Professor of Architectural History Louis Nelson, left, and graduate assistant Kyle Edwards, right, to tour the small building.

Plaskon has lived and worked in Monroe’s former law office for five years and said he feels like he’s “channeling Monroe.”

He oversees one of Brown College’s vibrant features: a varied slate of short courses, programs and activities, including a course he teaches, “Backstage at U.Va.,” which often brings in U.Va. deans and alumni.

Montes-Bradley expects the film project to wrap up sometime in the fall, after he’s able to add certain fall scenes.

“Monroe Hill” should serve as an appropriate piece of U.Va.’s upcoming bicentennial, he said.

Media Contact

Article Information

July 1, 2015

/content/documentary-illuminates-history-overshadowed-monroe-hill