On Dec. 7, 1941, hundreds of Japanese fighter planes tore through the silence of a clear Hawaii morning, raining bombs and bullets down on Pearl Harbor’s unsuspecting servicemen and bringing the United States into World War II.

Seventy-five years later, activists nationwide, including University of Virginia students and faculty members, are still working to research and memorialize the soldiers killed that day.

Dr. Gregory Saathoff, an associate professor of research in public health science and emergency medicine, directs UVA’s Critical Incident Analysis Group, which studies responses to major attacks like Pearl Harbor, or more recently, the Sept. 11 attacks.

Saathoff is also a board member of the local nonprofit ParadeRest, which works with UVA students, faculty and community members to seek out and honor local veterans of recent wars back to World War II. He leads a team of several UVA students recording veterans’ oral histories and gathering photographs and information about nearly 800 local veterans for ParadeRest’s “Finding the Fallen” project.

Gregory Saathoff worked with students to search materials in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library for clues about UVA students killed in combat. (Photos by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications)

“Every World War II veteran that we have spoken with – almost 70 so far – mentioned exactly where they were when Pearl Harbor occurred,” Saathoff said. “It was certainly a galvanizing experience for them and their families, and for the country as a whole.”

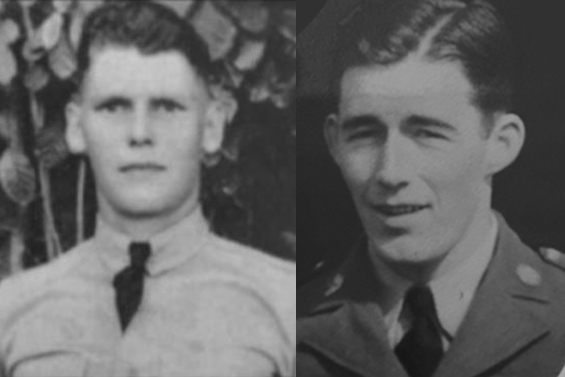

So far, Saathoff’s team has identified three servicemen from Albemarle County killed in the Pearl Harbor attacks: James Merritt Barksdale, a staff sergeant in the Army Air Corps, who was killed at Wheeler Army Airfield during the first wave of attacks; Corp. Emmet Edloe Morris, killed at Hickham Field, an Air Force base adjacent to the harbor; and Alwyn Berry Norville, who served in the Navy and died aboard the USS Nevada, one of eight U.S. battleships that were heavily damaged that day.

Emmet Edloe Morris, left, and James Merritt Barksdale hailed from Albemarle County and were both killed during the Pearl Harbor attacks. (Photo courtesy of ParadeRest)

Their investigation prompted other members of the UVA community to share their war stories.

Adrienne Weinberger, wife of UVA biochemistry and molecular genetics professor Dr. Edward Egelman, told Saathoff about her parents, who were working in Pearl Harbor at the time of the attacks.

Weinberger’s mother, Marta, grew up in Trieste, Italy, but began a pen pal relationship with her cousin’s American friend, Samuel Weinberger, who worked as a naval architect at Pearl Harbor. They fell in love, she came to the U.S. to be married on Christmas Eve in 1940, and later they were among the first to respond to the Pearl Harbor attacks. Samuel did not come home for four days, Weinberger said, as he helped fight fires on the base and deal with the attack’s aftermath.

Adrienne Weinberger holds a photo of her parents. At the time of the attack, Marta Weinberger worked for the Army and Samuel Weinberger designed naval ships.

“They really fell in love over the mail,” said Weinberger, who still has her mother’s memoir. “I am fortunate that my mother wrote all of these things down, because it is a wonderful story.”

For second-year student Cameron Haddad, who began working with the Critical Incident Analysis Group as a work-study student, learning about veterans like Barksdale, Morris and Norville and hearing stories like Weinberger’s lent emotional weight to what he was learning in class.

“Reading about Pearl Harbor in history textbooks, you think of it as an event, but there is not a real, tangible connection with it,” said Haddad, who is majoring in economics and minoring in history. “Hearing these veterans’ stories and looking at veterans who died at age 19, 20 or 21, it was shocking to think of myself in their shoes. It has allowed me to really connect with and understand the history.”

Among the memorabilia Weinberger has collected from her parents are several newspaper columns Marta wrote on life in Europe – particularly Italy – during the war.

Roughly 200 veterans killed in World War II have been identified as hailing from Albemarle County, many with UVA ties.

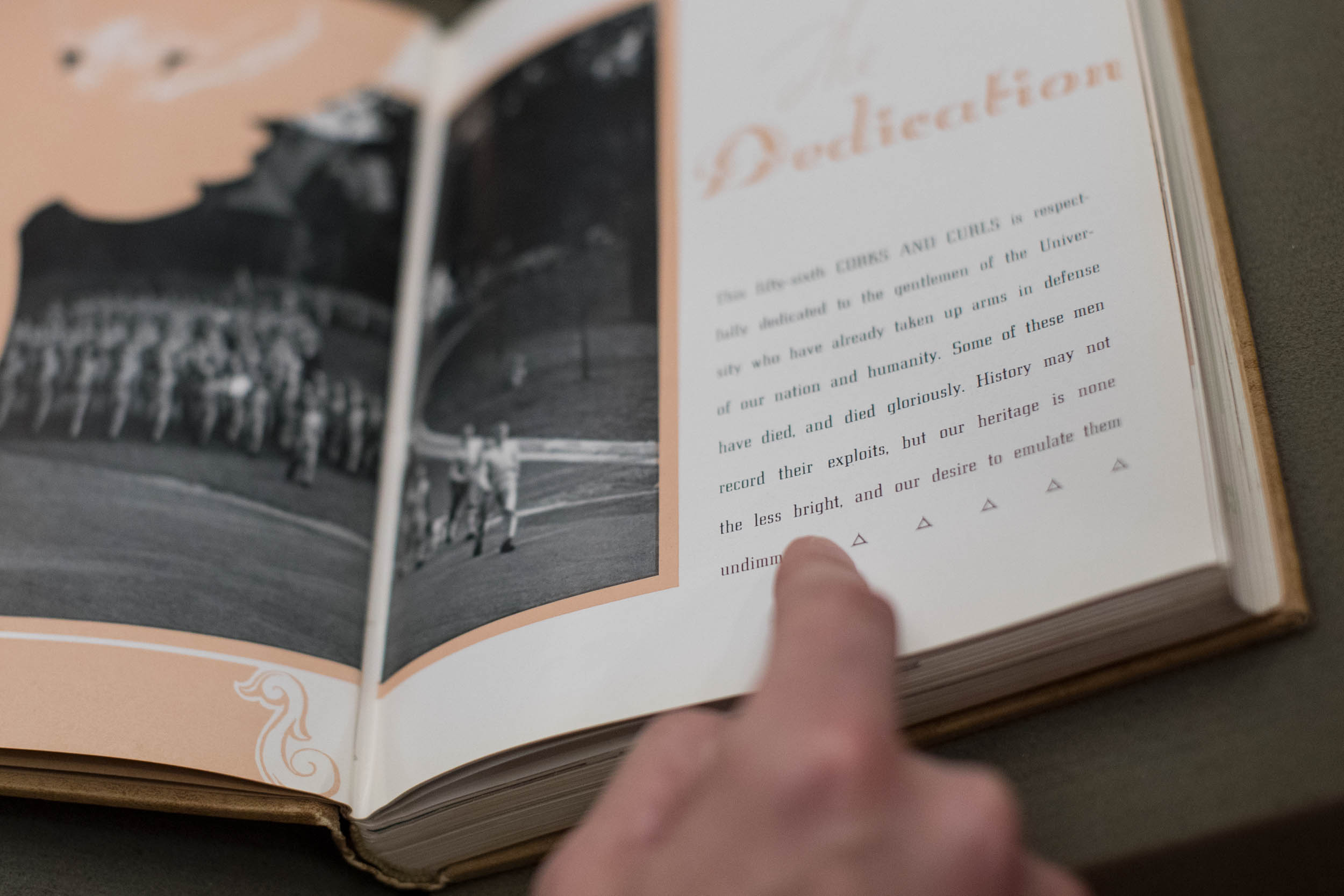

At the University, the war’s impact was pervasive. Less than a year after Pearl Harbor, a plane with faculty and staff from UVA’s schools of Medicine and Nursing landed in Casablanca, Morocco to begin a combat hospital, which they fully staffed. Later, the UVA detachment moved to the European front. Among students, a 1942 University yearbook noted that it was a “year of war” with air raid squads on the Lawn and many students leaving to enlist in the military.

“One of the things that we are finding is that there were many UVA students who left school after one or two years to join the war effort and never came back,” Saathoff said. “It is important to identify these people and recognize them and their link to our community and university.”

The 1944 edition of the UVA Yearbook, Corks and Curls, was dedicated to UVA students who fought in the war.

Saathoff, Haddad and others are tracking down surviving family members and finding out as much as they can about each person killed, so that they can share not only their names, but their pictures and stories. Each Memorial Day, his team works with ParadeRest to put together a tribute video shown at Charlottesville’s Paramount Theater. Students also conduct interviews with local veterans who survived the war for another ParadeRest project, called “A Nickel for Your Story.” Haddad estimates that he has recorded the oral histories of 10 veterans, including a few who served in World War II.

One such veteran, U.S. Army Gen. Edward Rowny, went on to become an influential figure in military and foreign policy. A three-star general now nearing his 100th birthday, Rowny serves as an adviser to the Critical Incident Analysis Group. He was one of 12 senior advisers helping U.S. Army Gen. George Marshall plan the conclusion of the war in Japan, served as a spokesman for U.S. Army Gen. Douglas MacArthur and advised five presidents on arms control.

When the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor, Rowny had just graduated from West Point and was stationed in Fort Bragg, North Carolina. He heard about the attack on a small handheld radio while sitting around a campfire with his fellow soldiers, reviewing lessons learned from a three-day training exercise they had just completed.

“We knew more about the war in Europe and had our minds set on training to fight in Europe,” he said. “The attack came as quite a shock.”

Rowny’s commanding officer, Army Col. Joseph Wood, volunteered his unit to be the first to go overseas after war was declared. Rowny served that first tour of duty in Africa and later served in Italy until the end of the war in Europe, when he joined Marshall’s strategic planning division.

Speaking with veterans like Rowny “is incredible” for the students, Saathoff said.

“They have so many important memories to share and, more than just being beneficial to the veterans and their families, capturing those memories for future generations is an investment for their education about freedom,” he said.

As a member of one of those younger generations, Haddad wholeheartedly agrees.

“It has just been fantastic, getting a perspective that a lot of people my age would never get,” Haddad said. “I have learned a lot about our veterans and it has given me a very strong appreciation for everything they do.”

Media Contact

Article Information

December 6, 2016

/content/75-years-after-pearl-harbor-students-faculty-chronicle-pearl-harbor-stories