They’re called “Oklahoma drills,” and most anyone who has played football recognizes them. The details may vary – for some teams, it’s a blocking drill; for others, a tackling drill – but the basic concept is the same: two players, lined up helmet-to-helmet in a confined space, each try to defeat the other as the rest of the players watch and wait their turn. It’s the closest thing to gladiatorial combat to be found in team sports.

Winning or losing is secondary. The main thing is not to back down. Sure, there are appreciative whoops and hoots for a dramatic hit, but even for the player on the receiving end, getting up, getting back in line and being ready to do it again earns respect.

Now imagine what it was like to have been Marcus Martin in the fall of 1967. That’s when he tried out for the football team at North Carolina State University as an undersized, non-scholarship player who had spent the previous fall playing trumpet in the Wolfpack marching band.

Also, he was the only African-American on the field.

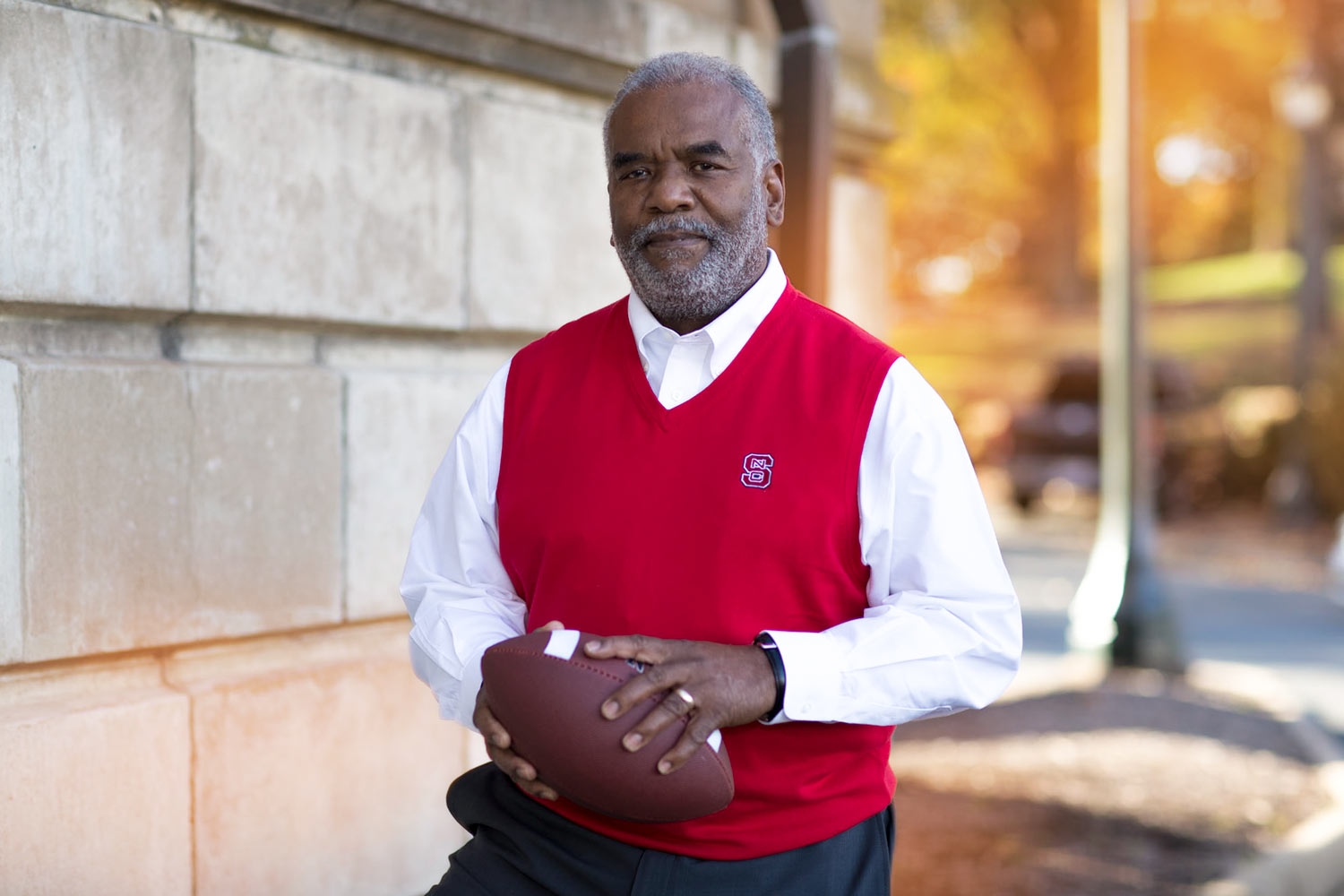

“We had this Oklahoma drill, where you go nose-to-nose – you’ve gotta go after one guy, and the guy’s going after you, until the coach blows the whistle,” Martin recalled recently in his office in Madison Hall at the University of Virginia, where he is now the school’s chief officer for diversity and equity. “Once in awhile I would win, but quite often I would be on my back.”

One might think that would be a painful memory for him, but he insists it’s not. “It was all in fun, all in building strength, building camaraderie. Of the 80-plus guys on that team, I did not have a problem with any one of them. And we’re talking 50 years ago.”

In October, N.C. State honored that Atlantic Coast Conference champion team at a home football game against Clemson University, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of its 9-2 season. Then, as it was five decades ago, Martin was the only black player on the field – and the first on the varsity team in the school’s history.

1967 was a year of tumult. There were huge protests against the Vietnam War, and race riots in many American cities. Segregationist Lester Maddox was sworn in as governor of Georgia, while Thurgood Marshall was confirmed as the first African-American justice on the U.S. Supreme Court. Muhammad Ali refused military service. The “Summer of Love” happened.

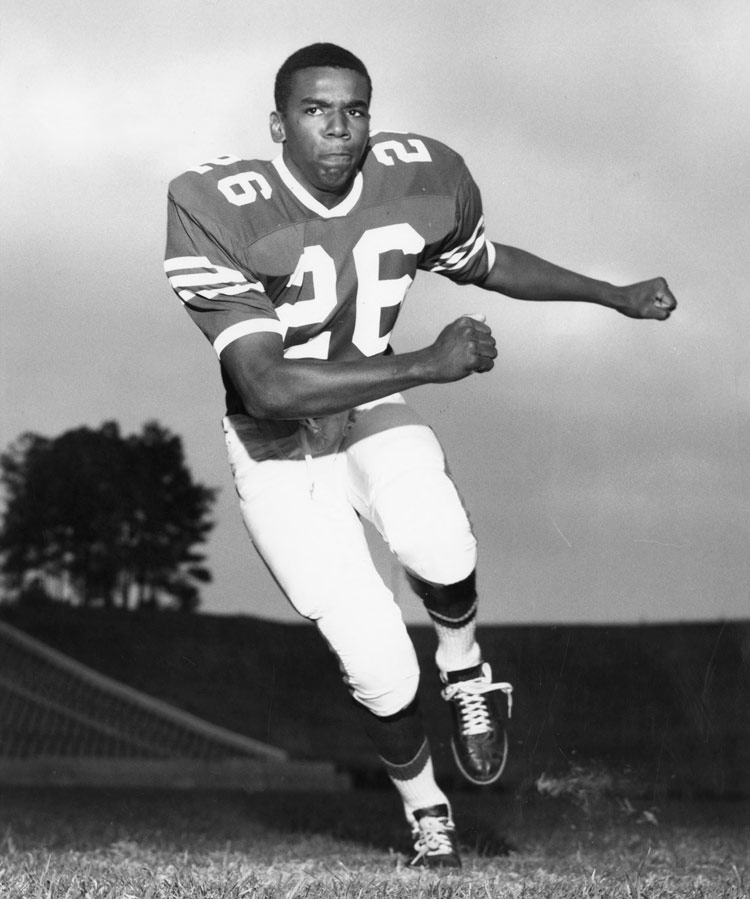

Martin was an undersized defensive back when he walked on to the N.C. State football team in 1967. (Photo courtesy of North Carolina State University)

Martin insisted that trying out for the football team at N.C. State was not a political act. He just wanted to play football again.

“It was about the experience for me,” he said. “I knew I was not going to be a big-time college football player. I didn’t have any aspirations for the pros. It was all about the experience and the opportunity. I’ve always had the mindset of having a can-do attitude, and not thinking about what I can’t do.

“Maybe that meant I was a little crazy, too, coming along. But I wasn’t afraid to take a chance.”

Humble Beginnings

Martin grew up in Covington, a small Virginia town not far from the West Virginia border. Its main business, then as now, was the paper mill. A distinct odor hovers over the town on most days. “People say it’s the smell of money,” Martin said.

Martin’s father, who had a sixth-grade education, labored in the mill, and was a respected member of the community. The family lived across the street from the black high school, Watson High. The schools were in the process of integrating; Martin recalls having the option to move to Covington High for his senior year, but opted to stay at Watson.

“I could look out of my bedroom window and see the football field, the practice field,” he said. “It wasn’t much of a field; it was a cow pasture, with rocks and other things you can imagine on a cow pasture.”

The school was small and tightknit; Martin said there were 20 boys and 20 girls in his graduating class.

“We got to do everything. We had to do everything,” he said. “I tell students, imagine playing football – I was the quarterback, a team leader; I was on defense, a defensive back, safety. And at halftime playing the trumpet in my cleats, marching at halftime, entertaining the crowd. I had about five minutes to go in and talk to the coach, eat an orange and come back out onto the field to start the second half.”

He sang in the glee club and played in the symphonic band, too. “But we never had the opportunity to be skillful in any of those particular areas,” he said.

The paper mill sponsored a scholarship that allowed students to attend N.C. State and major in pulp and paper technology, work at the mill in the summer and then return full-time after graduation. Martin applied; he credits his father’s standing in the community with helping him be one of the two winners, with the other coming from Covington High.

Arriving in Raleigh

North Carolina was only six years removed from the Greensboro sit-ins, but Martin does not recall feeling unwelcome in nearby Raleigh. N.C. State had a small population of African-American students who supported one another; some would make their way to Raleigh’s black schools, Shaw University and St. Augustine’s College, for parties.

“The climate at N.C. State was inclusive, and a lot of it had to do with the type of students recruited there and what we were studying – serious students in the STEM fields,” Martin said. “I’m a social person and went to my fair share of the parties, but there was a lot of time spent studying.”

Martin had added a second major, chemical engineering, to go with the scholarship-required pulp and paper technology program. That meant a heavy courseload of up to 21 credit hours per semester; summer school was not an option, as Martin needed to return to Covington and do research projects in the paper mill to save money for a fifth undergraduate year.

That didn’t prevent him from joining the N.C. State marching band as a freshman, where he again took up his trumpet. “My very first game in Carter-Finley Stadium, I was playing in the band,” he said.

It was a busy life, but he found he still missed football. He decided to try out.

“I didn’t look at the team to say, ‘I’m going to integrate the team,’” he said. “I didn’t look at the team to say, ‘Here is a position I am suited for.’” He just wanted the experience, the chance to work hard at something and see if he could get better.

Walking On

Taking stock of himself, Martin knew going in that he had some limitations. He was skinny, at about 5-foot-10 and around 170 pounds. The team’s quarterbacks were light years ahead in terms of training and skills. He had some speed, but so did most of the other players his size. “I knew it would have to be something like defensive back or running back,” Martin said.

“When I learned he was trying out, I thought he was crazy,” teammate Ben Lemmons said. “Then when he performed and struggled like the rest of us, he was just one more player trying to make the team. I think the coaches and the players thought he was extremely brave doing this.”

Martin made the team, and said he was happy with that – though, like any player, he dreamed of being a starter. “I didn’t start, but I played on the kickoff team and I was a backup to the starters at cornerback,” he said. “And I remained as a backup.”

The practices were hard. As a member of the scout team, he regularly competed against the starters. He earned the respect of his teammates and a reputation as a hard hitter.

“The coaches were tough,” he said. “The coaches would tell me, you know, when I’m on the ground, ‘Get up, don’t feel sorry for yourself.’ I understood exactly what they were talking about; football is a tough game, but in the long run it made me perhaps a tougher person, appreciating the skills of others, but also appreciating being included.”

The head coach at the time, Earl Edwards, “made sure that things were happening in the right way for me,” Martin said. “[The coaches] didn’t treat me any differently. I think they expected me to live up to what I could do in terms of talent.”

Martin’s roommate one year was Art Padilla, an outgoing student who wore the school’s wolf mascot costume, which he kept in a closet in their room. (Martin said he knew Padilla was out “mascotting” if the wolf’s tail was no longer sticking out from under the closet door.)

Padilla remembers Martin as a serious student. “I would come back to our dorm room usually around 10 or so from having gone out to eat or from goofing off,” he said. “Marty would be laying on his bed, in the dark, moaning.

“I would ask him, ‘What’s up, man?’ He’d always reply, ‘Licking my wounds, like a lion.’”

But then Martin would rally, roll out of bed and study until the early morning hours.

“How Marty could remain focused in his schoolwork was always impressive,” raved Padilla, who went on to become an administrator and professor at N.C. State and the universities of North Carolina and Arizona, and remains close to Martin.

Team sports in general, and football teams in particular, are often bastions of diversity and inclusiveness. For the team to have success, it needs contributions from all of its members. Racial divisions are poisonous.

“I’m sure [racism] was all around us,” Lemmons said. “But [Martin] had the respect of all of us, and he was part of our team and one of us.”

Of course, Martin’s acceptance at N.C. State was not necessarily transferable to other teams and their fans as the Wolfpack played their Atlantic Coast Conference schedule. Many of the teams they faced, including the University of Virginia in Martin’s home state, were not yet integrated. “Duke may have had one or two players, but that was something you did not see,” Martin said.

Martin was not always a member of the travel team – a slightly smaller subset of the full team that would compete in away games – but he did recall playing at the University of South Carolina. After a play, he found himself at the bottom of a pileup, “the other team spitting and kicking. Those were some tough times.”

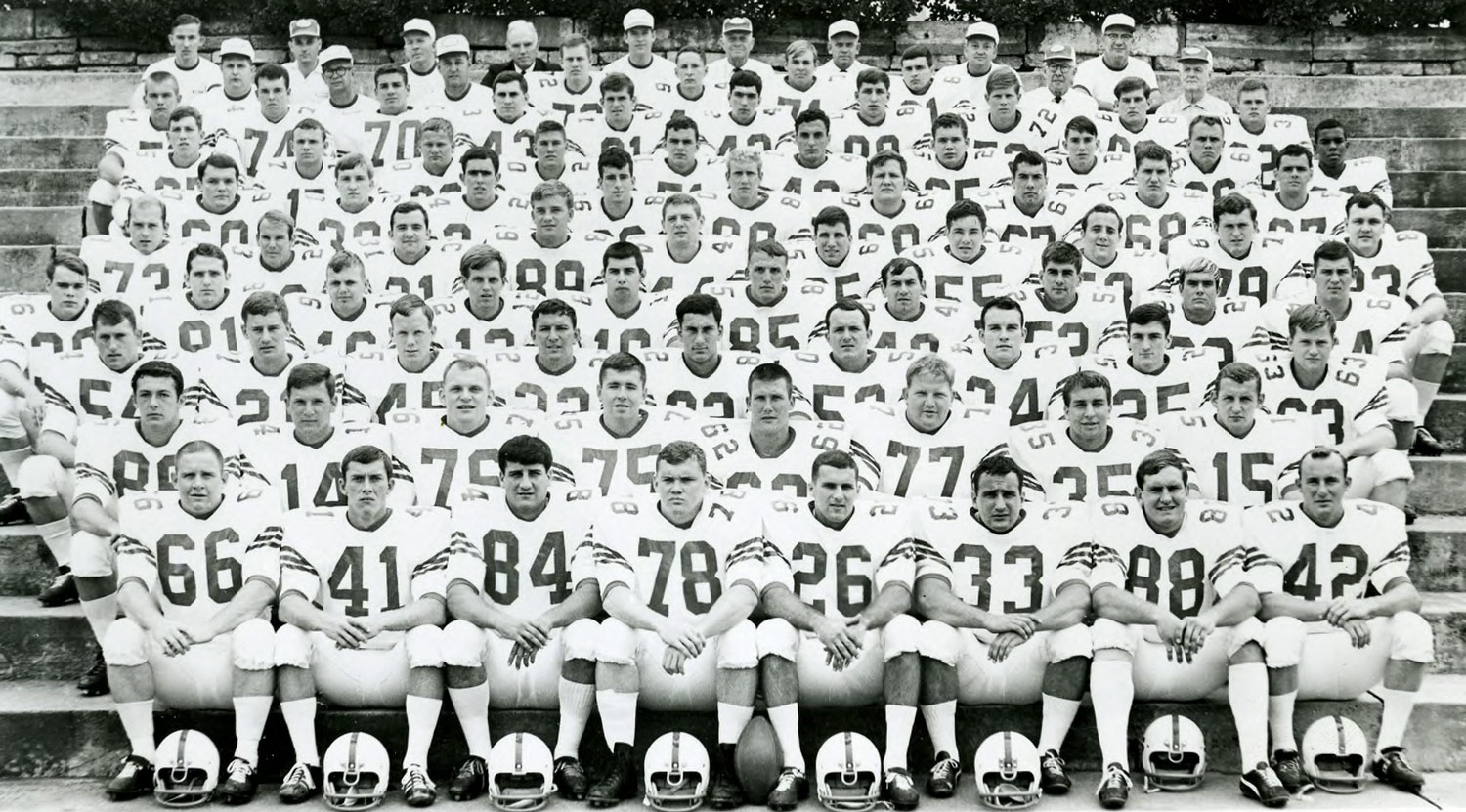

But Martin chooses not to dwell on those experiences. In his office at Madison Hall, he has two team photos, from the 1967 and 1968 teams. He likes to play the “Where’s Waldo?” game with visitors – can you find the lone black guy in the sea of white faces? – but he also starts to point out some of the players who had his back, before giving up. “I could go to just about any guy on this page and say they were supportive,” he said. “They accepted me.”

As the only African-American player on the roster, Marcus Martin was a singular presence in this 1967 team photo. His teammates, he said, were supportive of his inclusion. (Photo courtesy North Carolina State University)

Martin played for two seasons before choosing to leave the team to focus on his academics. He knew it was unlikely he would ever become a starter, and that he had to finish his courses in five years or run out of money. He also had helped establish N.C. State’s chapter of the Alpha Phi Alpha social fraternity, which demanded a lot of time.

Playing football “was definitely worth it. And I would do it again,” Martin said. “And perhaps knowing what I know now, I would try to do a little bit heavier training, particularly in the summertime. ... But the two experiences with activities on the field at N.C. State, marching band and as an athlete, I can’t say that too many people have that as part of their résumé – something they can reach back to and say it was character-building and I think propelled me in the right direction.”

Moving On

Martin did graduate on time, and returned to the paper mill in Covington, where he dutifully put in two years as a production engineer before applying to Eastern Virginia Medical School. His grades were good enough to win acceptance into a class of just 24 students, from a pool of 1,200 applicants. He was one of two African-American students who enrolled – a theme that recurs in Martin’s life.

He was the first African-American graduate of the emergency medicine residency program at the University of Cincinnati, the first African-American president of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, the first African-American president of the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors, and the first African-American chair of a clinical department at the UVA School of Medicine.

“The further you go up, the more likely it is you’re going to become a ‘first,’” Martin said. “At some point in history, you want to see that stop; you don’t want to see the ‘first’ anymore. You want to see more inclusion. But you can look back to say that you helped pave the way for others.”

Certainly, that’s true at N.C. State, where Martin went on to serve on the school’s Board of Visitors, appointed by former mascot/roommate Padilla. Looking at the old team pictures, Martin quipped, “You look at the N.C. State team these days, and you have to look to see where the white players are, because there are so many black players on the team, compared to then.”

Martin still glows as he talks about the 50th reunion this fall. Fifty of his 80 teammates – including Chuck Amato, who went on to some fame as the head coach at both his alma mater and at Florida State – showed up.

The team and its fearsome “White Shoes Defense” was recognized on the field during a break in the first quarter of the game with Clemson, to thunderous applause. The former players and their guests retired to the president’s box after the game for more socializing. The fellowship was just like 50 years ago, Martin said; “true camaraderie.”

Reflecting on his journey, Martin said, “There’s a Maya Angelou saying, when ‘we give cheerfully and accept gratefully, all are blessed.’ It’s just a blessing to be where I am now, and to have come from where I came from. And it all started with having a loving family, two parents, and being in a community that looked out for me.”

That sense of gratitude has inspired him in his current position, he said.

“There are a lot of students at the University of Virginia with varied backgrounds, different races, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, that I do all I can for – particularly opening doors, opportunity-wise, through the STEM fields, and also through medicine,” he said. “I mentor a lot of students, give them advice, and tell them about my background, and in a lot of cases write letters of recommendation and support for them, because opportunities and doors were opened for me on many levels.

“I was included. And so I want to see everyone included fairly and have the same type of opportunities that I had.”

Reflecting on his long journey from Covington to Madison Hall, Martin said, “It’s just a blessing to be where I am now, and to have come from where I came from.” (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Media Contact

Article Information

November 20, 2017

/content/football-first-helped-propel-marcus-martin-paper-mill-madison-hall