Only with a fuller understanding of individual, local, state and national history will people be able to answer the question the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. posed near the end of his life: “Where do we go from here?” That was the consensus of panelists who gathered Tuesday night at the University of Virginia to ponder King’s lasting impact.

Throughout 2018, a series of discussions are being held in Virginia communities that King visited as he fought for civil rights for African-Americans. King came to Charlottesville on March 25, 1963, and spoke to a packed house in UVA’s Old Cabell Hall auditorium.

To honor King’s life and legacy – 50 years after he was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee – the Virginia General Assembly’s Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Commission organized the events to reflect on King’s vision of a “beloved community” and to examine what is needed to improve equality and inclusion in the commonwealth. At UVA, a panel discussion hosted by the UVA Office of the Vice President and Chief Officer for Diversity & Equity was held Tuesday in the same venue where King spoke, Old Cabell Hall auditorium.

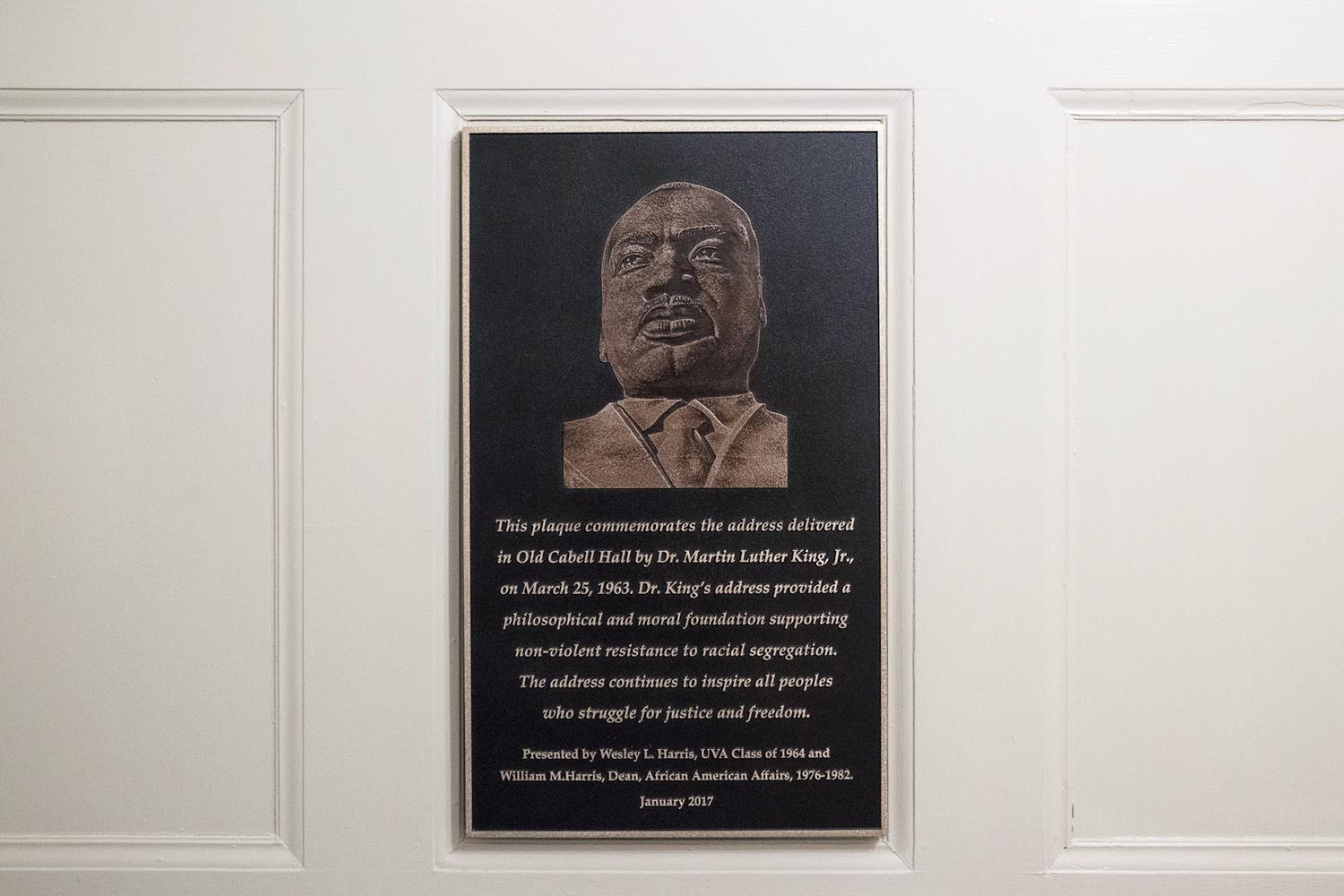

UVA recognized King’s 1963 speech on Grounds in January 2017 with a plaque in Old Cabell Hall, a gift from brothers Wesley and William Harris.

The event featured leaders from the community who addressed King’s question, “Where do we go from here?” King gave a speech with that title at the 11th annual session of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1967, a year before his assassination, and he also gave his fourth and final book that title, followed by the subtitle, “Chaos or Community?” Some of the panelists alluded to those works and other King writings.

State Sen. Jennifer McClellan, who chairs the state’s memorial commission on King, moderated the discussion and introduced the panelists: the Rev. Lehman Bates, pastor at Charlottesville’s Ebenezer Baptist Church; Andrea Douglas, executive director of the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center and a UVA alumna; Nikuyah Walker, Charlottesville’s newest mayor; one of the first black undergraduate students, UVA alumnus Wesley Harris, C.S. Draper Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who helped bring the civil rights leader to the Grounds; and UVA President Teresa A. Sullivan.

Sullivan mentioned that the University and local community have been working together on the annual Martin Luther King Community Celebration for eight years, with a variety of 20 or more events in January.

She also described one of her latest actions: creating the President’s Commission on the University in the Age of Segregation, to explore Virginia’s participation in the Massive Resistance movement in the 1950s.

“During this period, public schools here in Charlottesville were closed to prevent desegregation, although the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals eventually overturned the closings,” she said.

UVA recognized King’s 1963 speech on Grounds in January 2017 with a plaque in Old Cabell Hall. The plaque was a gift from brothers Wesley and William Harris, who both have deep UVA ties. Wesley, a 1964 graduate, helped bring King to Charlottesville for the historic visit, and his brother William served as dean of the Office of African-American Affairs from 1976 to ’81.

Wesley Harris, who said a high school teacher encouraged him to go to UVA, was one of only seven African-American male students in the School of Engineering and Applied Science in the early 1960s – the only undergraduate school that would accept black students at the time. Returning again to UVA for the panel, he said the small group that brought King to the Grounds needed his vision “to nurture their souls,” and that King did just that.

King laid out his basis for social justice, citing well-known philosophers, Harris said.

University leaders did not acknowledge King’s visit, but they did not block it. Harris said hearing King, who he called “America’s greatest advocate for social justice,” changed him forever.

Sullivan said Harris’ account of that time at UVA was moving, but despite the extreme loneliness of his and others’ experience, they paved the way for other African-Americans to come to the University. She mentioned that several thousand black alumni registered for the Black Alumni Weekend reunion last year.

In her own experience, Sullivan recalled attending a Catholic high school in Mississippi that integrated early and thus, “we were hated by the community.” She said that was partly why she became a sociologist – “to try to understand why people who seemed good could turn so ugly” in response to upsetting the status quo of segregation.

State Sen. Jennifer McClellan (left), who chairs the state’s Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Commission, and the panel of distinguished leaders, including UVA President Teresa Sullivan (second from right), reflected on King’s vision of a “beloved community.”

The Jefferson School’s Douglas, who earned her master’s and Ph.D. in art history from UVA, said in 1963 the city of Charlottesville was embroiled in its own fight for civil rights, with the local NAACP chapter especially trying to desegregate schools after had closed several years earlier in the “Massive Resistance” reaction to the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

“I believe that King’s visit in 1963 probably provided solace to the community pushing for desegregation,” she said.

At the time, plans were also being made to raze Vinegar Hill, a historically black neighborhood, in the name of “urban renewal,” Douglas said, which brought housing into the picture and tied it to education. She wondered if closing African-American schools and sending black students to white schools was the best way to integrate.

“Not all of us have accepted the notion that the system that was integrated was the

correct system anyway,” Douglas said.

Mayor Walker mentioned that within schools, segregation has persisted. A Charlottesville native, Walker, who is black, said this is a resource-rich community, but said those resources don’t reach those who most need them – especially African-Americans.

Sullivan said that “white flight” affected many American cities, and that in this locale, the borders and governance structure of city and county limit the city’s ability to deal with housing affordability. The University will continue to work with both to find ways to partner on such issues, she pledged.

On a federal level, the 1964 Civil Rights Act that outlawed discrimination in employment and in public places brought enormous change. Several speakers mentioned that not many people who lived through the Jim Crow era are alive now to remember it, and not enough people today know the history about what things were like for African-Americans.

When she talks with students about this history, Sullivan said they have a hard time believing it.

“What I hope we can do at UVA is help students learn about this so they have the ability to analyze the systems we live in and then look for ways to improve them,” she said.

Douglas echoed that need to educate not just children, but everyone, whether they are ignorant or racist, on the context of racial injustice.

Walker added that leaders must be willing to hold themselves and others accountable, and that it’s hard to be patient when swift action is needed to find solutions for issues such as equality in education and disparities in the criminal justice system.

King was aware of how far society was from his “dream,” but he laid out the path, focusing in his later work on ways to eliminate poverty, she said, wielding a book of his writings.

McClellan said part of the King Commission’s work is helping to tell the whole story about Virginia, so “when we make policy decisions, it’s with the full knowledge of the context.”

“To understand where we are going, we have to understand how we got here,” she said.

The first “Beloved Community Roundtable” program was held March 1 at Virginia Union University in Richmond. The next events will be held in Farmville (April 24), Williamsburg (June 6) and elsewhere in Virginia cities throughout the year.

The General Assembly established the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Commission, a bipartisan agency, in 1992 to honor King’s legacy through educational, historical and cultural programs, public policy analysis and public discourse on contemporary issues.

Media Contact

Article Information

March 14, 2018

/content/55-years-later-panelists-ponder-kings-question-where-do-we-go-here