The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 visit to the University of Virginia was the result of a small-but-determined group of students fighting an uphill battle for racial equality at a time when the nation was deeply divided.

Wesley Harris, then an African-American student raised in Richmond’s Church Hill neighborhood and now a professor of aeronautics and astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was at the center of that effort.

Harris enrolled at UVA in 1960 and immediately recognized that he would not be afforded all the opportunities of his white counterparts. Black students were not allowed to enroll in the College of Arts & Sciences at the time, he said, and Harris majored in engineering.

“My life’s desire was to follow my high school physics teacher and major in physics, but UVA would not allow blacks to major in physics,” he said.

Not long after, he and a tiny group of black and white students, “never more than a dozen,” formed the Thomas Jefferson Virginia Council on Human Relations.

“The first and primary objective of the Thomas Jefferson Virginia Council on Human Relations was to provide that safe space,” Harris said. “The second was to provide a platform to address the critical social injustice that was so prevalent on Grounds and in the greater Albemarle County.”

They wanted King on that platform at UVA, and turned for help to faculty adviser Paul Gaston, a history professor who knew how to get in touch with the civil rights leader.

The need to have King address the University, Harris said, was “obvious.” He and his black classmates, who numbered seven or eight in the undergraduate school, were regularly subjected to terrible abuse.

“This was, in my eyes as I remember it, some very dark times on Grounds,” Harris recalled. “Walking through Grounds on an evening at night, you would be presented with cigarette butts thrown from cars driving by, the N-word being yelled from cars being driven by.”

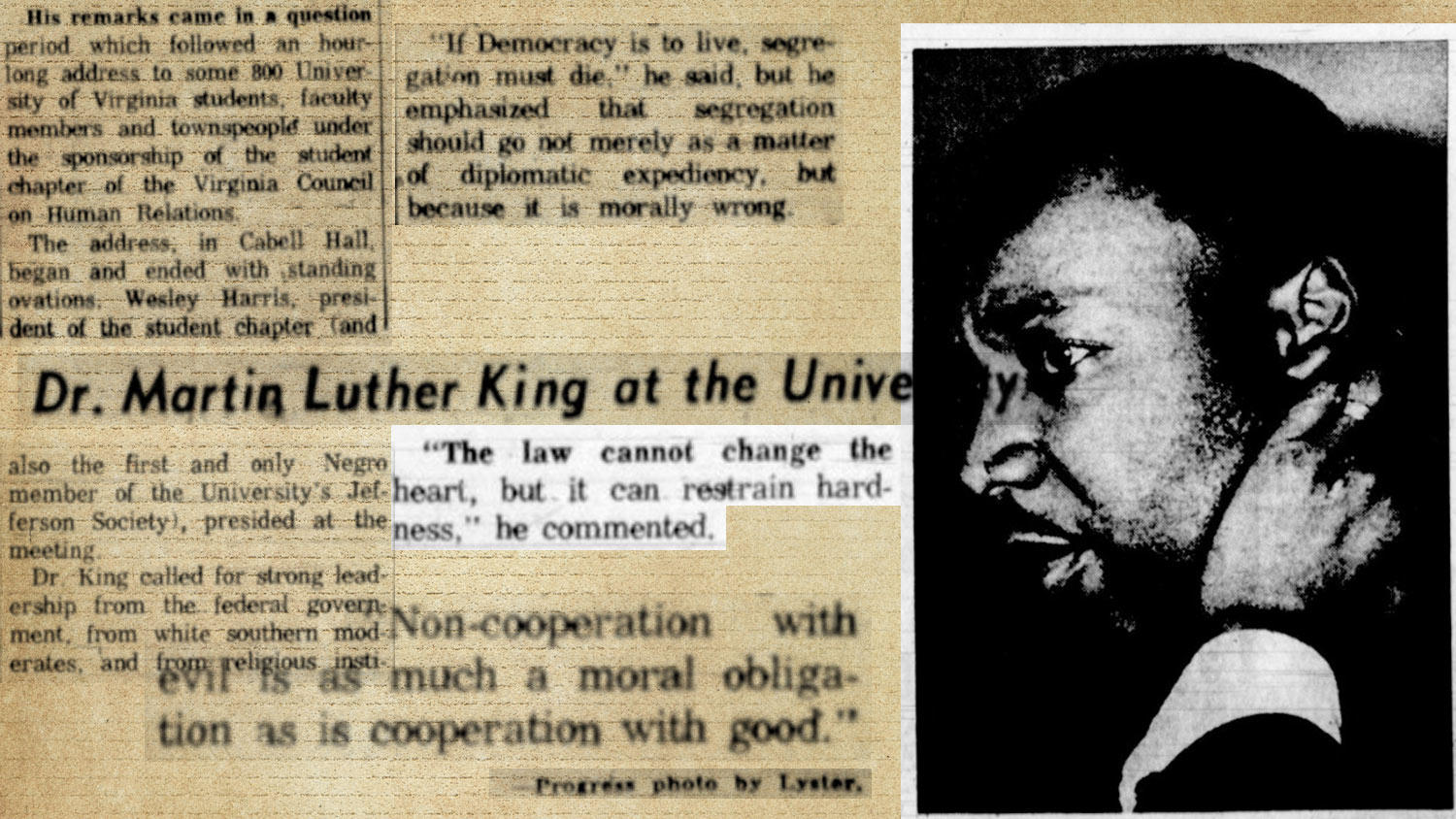

The student committee sent a letter of invitation to Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, where King preached. The reverend said he would come and the two sides agreed he would speak in Old Cabell Hall on the evening of March 25, 1963.

Harris said he remembers King’s arrival that day “vividly,” because King drove to Charlottesville by himself; there were no bodyguards, no entourage. “Usually when you see Dr. King in a photograph or a newsreel, he is always surrounded by people. He was not when he arrived at the University of Virginia,” Harris said.

King arrived late in the afternoon and Harris got him settled in a hotel that once stood on Emmett Street near the Lambeth Field Apartments, but recently suffered major fire damage. The pair then met Gaston and Gaston’s wife for dinner at the University Cafeteria, the only dining establishment on the Corner that would serve African-Americans.

While Harris does not remember specifics of the dinner conversation, he remembered King’s demeanor very well. “A very solid person, very quiet but very strong. Very direct eye contact – little words, but useful, profound words when he spoke,” he said.

Last January, brothers Wesley and William Harris presented a plaque commemorating Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s appearance at UVA March 25, 1963. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

After dinner, the group strolled around Grounds, touring the Lawn and other areas of the University.

Then something alarming happened. As they were crossing the McCormick Road bridge, a loud sound that sounded like a rifle shot rang out. Instinctively, Harris covered King.

“It just was spontaneous,” he said.

King’s reaction was to look at the young man. “I think he may have said ‘Brother Wes,’ and that was all.”

Harris had promoted King’s appearance in the city, especially to black churches. When the dinner companions arrived at Old Cabell Hall, it was packed with community members. Harris estimates about a third of the audience was white, and he was surprised at the size.

That was because University leadership, led by President Edgar Shannon, “basically ran away,” Harris said. “The University didn’t have the courage to acknowledge his presence – they simply didn’t.”

King’s speech about civil rights lasted no more than an hour. Rather than a rousing sermon, the audience heard a scholarly address. When he finished, Harris said, the hall was quiet.

“I think a lot of folks were stunned. I think many were expecting that Southern Baptist preacher, and that’s not what they got,” he said. “I think they were expecting quotes from Isaiah, and they got quotes from Kant.”

That evening, Harris and Gaston escorted King back to his hotel to offer their thanks and say their goodbyes. It would be the last time Harris would speak with the leader.

A few years ago, Harris was visiting Princeton University, where he earned his Ph.D. and serves in a leadership advisory position. In the Great Chapel at the school, he noticed a plaque commemorating King’s sermon there in 1960. Harris instantly thought UVA needed a similar plaque to honor King’s speech.

Last January, he and his brother William, UVA’s first dean of African-American Affairs from 1976 to ’81, returned to UVA for a dedication ceremony honoring King’s remarks. The plaque is installed in Old Cabell Hall, where King spoke 55 years ago.

Media Contact

Article Information

January 12, 2018

/content/how-rev-martin-luther-king-jr-came-speak-uva-1963