Famed artist Georgia O’Keeffe studied at the University of Virginia every summer from 1912 to 1916, taking courses designed for art teachers and teaching some classes of her own.

When she arrived, however, she was nearly ready to give up on art, lacking inspiration and struggling to work through her family’s financial struggles and, later, her mother’s death.

It was on these Grounds that the clouds slowly began to lift for her.

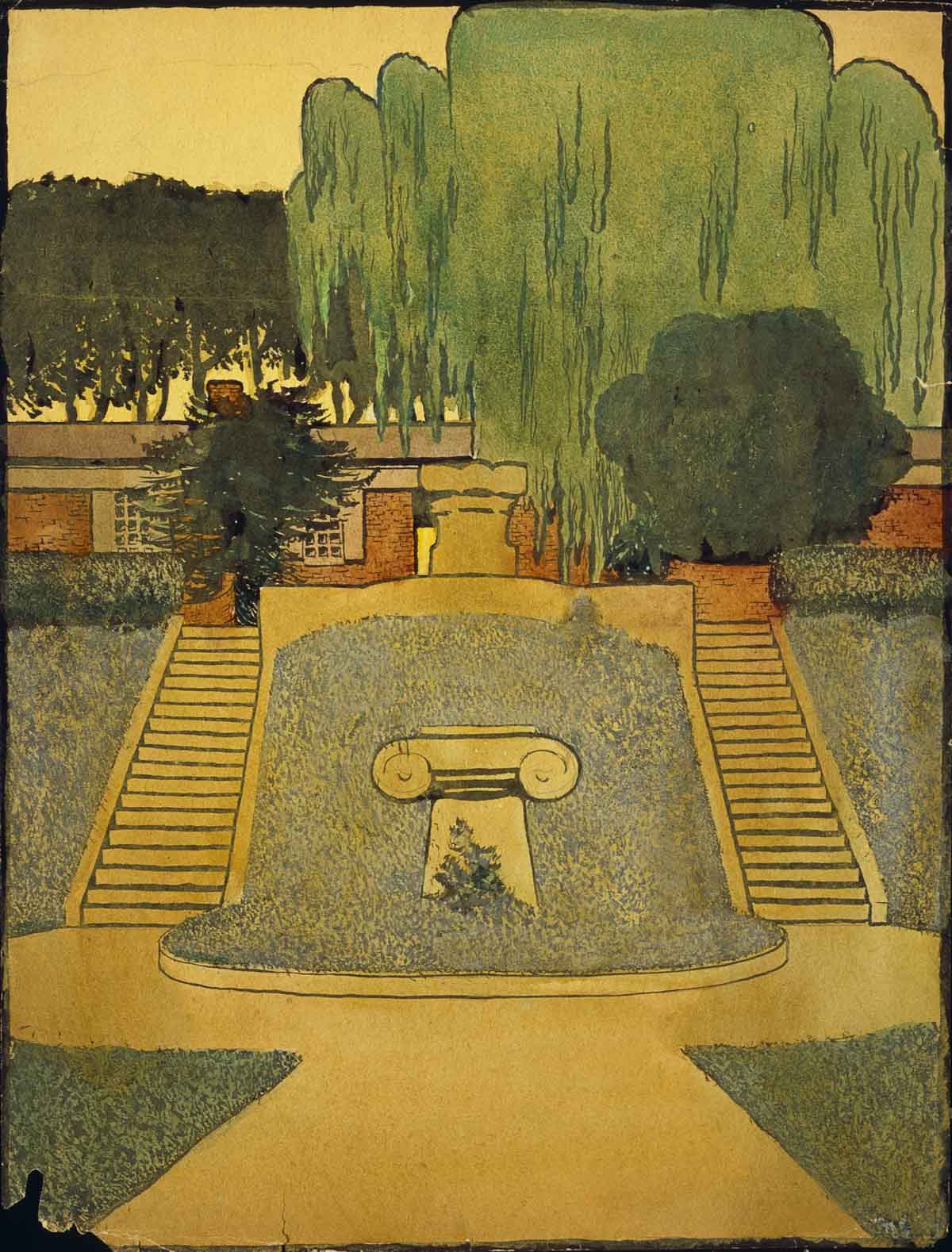

This was where she began her early experiments in abstract painting, drawing the buildings and gardens that she walked past every day on her way to class in Cocke Hall on the Lawn – watercolors like the one below, sure to thrill Cavaliers today.

In these classrooms, O’Keeffe first encountered the philosophy of Arthur Wesley Dow, an artist and teacher who would become one of her most influential mentors and shape her now-famous abstract style.

And it was in the Blue Ridge Mountains where O’Keeffe, like thousands before and after her, found inspiration, restoration and the courage to keep pursuing her dreams, even when they felt far out of reach.

A new exhibition opening this weekend at UVA’s Fralin Museum of Art, “Unexpected O’Keeffe: The Virginia Watercolors and Later Paintings,” chronicles these pivotal years of O’Keeffe’s life, long before she became a name still known around the world today.

The exhibition opens Friday and will run through Jan. 27. Visitors will find watercolors of Grounds, done for various assignments in O’Keeffe’s art classes; increasingly abstract paintings of the Blue Ridge Mountains; ink sketches; and even a sculpture. Archival materials – including photographs, books, periodicals and other memorabilia – paint a robust and fascinating picture of the University in the early 1900s. A new self-guided walking tour is also available, taking visitors to the same sites where O’Keeffe once sat with her sketchbook.

Left to right, Ph.D. student Meaghan Walsh, recent graduate Jonathan Chance, art history professor Elizabeth Turner and Fralin director Matthew McLendon prepare the soon-to-be-opened exhibition. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

All of it, according to Matthew McLendon, J. Sanford Miller Family Director at the Fralin, chronicles perhaps the only period in the famous artist’s life that has not been subject to intensive public and scholarly scrutiny.

“This is one of, if not the only, understudied period of Georgia O’Keeffe’s history,” said McLendon, who co-curated the exhibition with Elizabeth Turner, a professor of modern art and O’Keeffe expert in UVA’s McIntire Department of Art.

“She studied here at a critical time, a time when she actually thought she was going to stop pursuing art. It’s a transformative time for her, and we can trace how this transformation begun in Charlottesville carried on through the rest of her career, when she becomes the O’Keeffe that everyone knows now. That began here.”

Life on Grounds

Graduate students, working with McLendon and Turner, have spent months recreating O’Keeffe’s UVA for the new exhibition.

When the 25-year-old O’Keeffe arrived in 1912, the University was in the midst of a transformation. The effects of the Rotunda fire of 1895 were still evident, both in the brand-new or newly restored buildings and in the budding landscape, which had only just begun to regenerate.

The Rotunda in 1913, as seen from the north, a view O’Keeffe captured several times. Image: Rufus W. Holsinger (American 1866-1930). Rotunda, 1913. Dry-plate glass negative. Holsinger Studio Collection, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia Library.

Though women would not be fully admitted for decades, more and more female students were making their way to Grounds through programs like the one O’Keeffe attended, a summer program designed to provide supplementary education for teachers.

Almost 2,000 students enrolled in the program each summer, and the vast majority of them were women.

“We have this idea of UVA as a homogenous, male space at that time, and it was not,” McLendon said. “There were very active summer programs that brought many women to Grounds.”

O’Keeffe’s former home on Wertland Street, where UVA students still live. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

O’Keeffe, who worked as an art teacher at colleges in Texas and South Carolina during the academic years, attended the program for consecutive summers from 1912 to 1916, first as a student and then as an instructor.

While in Charlottesville, she lived with her mother and two sisters in her mother’s boardinghouse on Wertland Street, a building that still houses students today.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American 1887-1986). Untitled (West Lawn - University of Virginia), Scrapbook of UVA,1912-1914. Watercolor on paperGeorgia O’Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation (2006.05.618). © 2018 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Artists Rights Society.

Many current students will recognize the pattern of O’Keeffe’s life at UVA, as pieced together by Jonathan Chance, one of Turner’s students, who spent this summer conducting research for the exhibition.

Chance, who also works as an assistant winemaker at a local winery, earned his bachelor’s degree from the School of Continuing and Professional Studies in May.

“We wanted to figure out who she was, who she knew and what the University looked like then,” he said.

O’Keeffe began her day early, attending classes for about two hours in the morning. Like many of today’s students, she walked from her home on Wertland Street, up the Corner and toward the Lawn, via the East Range. This painting, for example, depicts a portion of the East Range, though it was later mislabeled as the West Range.

O'Keeffe's classes were in the building next to Old Cabell Hall, now called Cocke Hall, at the time called the Mechanical Laboratory. It was a relatively new building, built after the fire to house engineering, drafting and drawing classes.

Outside of class, O’Keeffe could have joined fellow students for the summer program’s excursions to Monticello or Natural Bridge, or socialized at dances held in Fayerweather Hall, which was a gymnasium at the time. She sent postcards from the Natural Bridge in August 1916, visiting with friends before she left Charlottesville.

Female students at a themed dance outside Fayerweather Hall in the summer of 1914. (Image courtesy Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

Despite sharing in these patterns and activities with her fellow students, O’Keeffe stood out. The boldness and singularity that would characterize the artist – she would become known for her solo trips into the harsh desert landscapes of New Mexico – were already very much in evidence, and she was very well-traveled for someone so young.

“She was an incredible traveler, even at a young age,” Ph.D. student Lucia Colombari said. “By the time she was 25, she had already lived in five states and seven cities. Considering the social constraints for women at the time, it’s quite impressive.”

In the few contemporary photographs we have of O’Keeffe and her sisters, taken by local photographer Rufus Holsinger, Georgia O’Keeffe appears to be a woman who does not hesitate to step outside the norm.

Left to right: Ida, Georgia and Anita O’Keeffe. In these photographs by Rufus Holsinger, Georgia O’Keeffe’s style clearly stands apart from that of her two sisters. (Images courtesy Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

“Georgia looks very different than her sisters, who are very traditional in their style for that period,” McLendon said. “When she comes to UVA, she already has a different sense of herself and her style, and people take notice. They realize that this family and this woman, in particular, are not like everyone else.”

A Life-Changing Class

Singular though she was, O’Keeffe was far from sure of herself when she arrived on Grounds in 1912.

Her mother was suffering from tuberculosis and her family was struggling financially, one reason she was working as a teacher instead of pursuing her own art full-time. She had also grown frustrated with the styles and techniques taught in traditional art lessons, finding them repetitive and uninspiring.

“Here is a woman who, all of her life, wanted to be an artist, who had attended some of the best art schools that encouraged her,” Turner said. “When her family fell on hard times financially, she gave it up. That is pretty remarkable. For almost four years, she does not think of herself or her future as being an artist.”

That changed when O’Keeffe took her first course at UVA with Alon Bement, a visiting artist who taught in the summer program. Bement introduced O’Keeffe to the design philosophies of Arthur Wesley Dow, an American artist and educator whose ideas would become the foundation of American modernism.

Dow believed that art should not imitate or copy nature, as was the case in the descriptive style taught in most academies at the time. Instead, he argued art should express a scene through design and composition. The artist, he contended, was akin to a designer, creating, inventing and building space instead of painting all of the details exactly as they appeared.

“When Bement starts talking about this form of empowered, inventive art, a way of life, really, it changed her,” Turner said. “It’s really remarkable just how quick that awakening was for her.”

Georgia O’Keeffe (American 1887-1986). Untitled (West Lawn - University of Virginia), Scrapbook of UVA, 1912-1914. Watercolor on paper. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation (2006.05.615). © 2018 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Artists

O’Keeffe would later move to New York to study under Dow himself, but his ideas immediately start showing up in her student notebooks at UVA, which she filled with watercolors of Grounds like this one, again of the East Range, later mislabeled as West Range.

In them, O’Keeffe uses trees and other elements to carefully frame buildings and create symmetry, as seen in her paintings of the gardens and range rooms, or of the Rotunda. The paintings are not designed to replicate the scenes down to the last detail, but rather to provide deliberately designed images of what O’Keeffe sees and feels as she paints on Grounds.

For example, Exercise No. 34 from Dow’s book, “Composition,” asked students to create “a landscape, reduced in its main lines, all detail being omitted.” That is exactly what O’Keeffe did in her student watercolors, using symmetrical lines and shapes to lead the eye.

“Looking at Dow’s philosophies, you can see how she takes them in as a student, testing them out for herself,” said architecture Ph.D. student Lauren McQuistion, who took a course with Turner this semester and worked on the exhibition. “It felt familiar to me because it is similar to how design students today are taught to understand and create space.”

The UVA watercolors marked the beginning of O’Keeffe’s journey toward the abstract style that would make her famous, as she increasingly focused on just a few powerful shapes and lines, packing a lot of emotional punch into sparse details.

During her last summer at UVA, she took an additional step toward that style in the beautiful Blue Ridge Mountains, where she fled during a time of heartbreaking grief.

Restoration in the Mountains

When O’Keeffe returned for what would be her final summer in Charlottesville in 1916, she was reeling from her mother’s death earlier that year.

Her letters from that time were despondent and hinted at depression, as she wrote about not wanting to do anything but sleep and expressed no enthusiasm for her art.

“She wrote that she taught for about two hours and then would go home and sleep for the rest of the day,” Chance said. “She was exhausted, and possibly depressed.”

O’Keeffe turned to a familiar place and ritual for comfort. She had often visited Elliott Knob, a peak on Great North Mountain near Staunton, with friends. O’Keeffe returned there to camp, and then a week later camped with friends at Humpback Rocks, familiar to UVA students as one of the most popular short hikes near Charlottesville.

True to her reputation as a rugged individualist, she slept outside her tent directly on the rocks, under the stars.

“When she writes that she slept out on the rocks, she means it literally,” Chance said. “It was something she enjoyed and would do over and over again later in New Mexico. She was very rugged, very tough and she wanted to be right in nature.”

Uncomfortable as it sounds, the ritual seems to have had its desired effect. O’Keeffe began painting again – colorful watercolors of mountain scenery that are more abstract than most of her work to that point.

“She writes that camping ‘got things going’ again,” Chance said. “We start getting watercolors again, right after these camping trips.”

Georgia O’Keeffe (American 1887-1986). Inside the Tent While at U. of Virginia, 1916. Oil on canvas. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation (2006.05.039). © 2018 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

The scenes she painted are familiar to any ’Hoo, evoking the undulating mountains that form the backdrop to Grounds itself and have long called to any student wanting to escape to nature for a little while.

“If you have lived in Charlottesville, you will be able to identify with her idea of the mountains,” Turner said. “You see the lines of the hills, the remarkable blue color that we all experience. That color, when I look west from Beta Bridge as the sun is going down, never fails to amaze me. You don’t think of blue as warm, but in our region, there is real life and vigor and warmth in it.”

A Lasting Legacy

Like many UVA graduates today, O’Keeffe went from Grounds to New York City, where art dealer and photographer Alfred Stieglitz held an exhibition of her work in 1916, followed by a solo show in 1917. She started studying under Dow himself, who taught at Columbia University Teachers College and married Stieglitz in 1924.

Her work grew bolder and more abstract, taking Dow’s philosophies to greater extremes and transforming natural and architectural forms into abstract shapes. She began spending more and more time in New Mexico, finding inspiration in its stark desert landscapes. She moved there permanently after Stieglitz’s death in 1946, and Santa Fe is now home to the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, established after her death in 1986.

Though her work evolved significantly after she left Charlottesville, McLendon, Turner and her students see echoes of her time here even in later works.

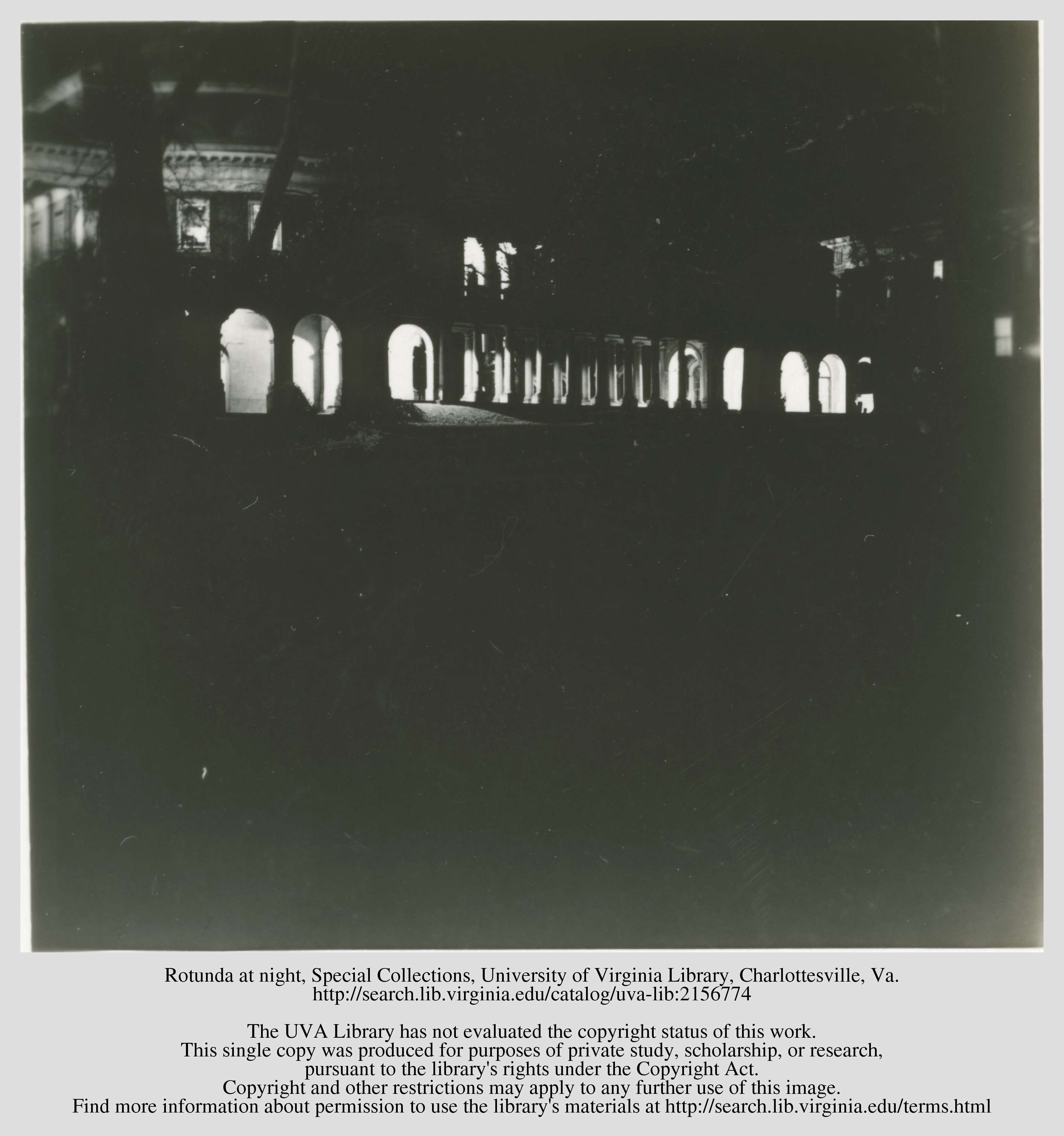

Chance, for example, found a reference to the arched passageways underneath the Rotunda, a shape that shows up abstractly in O’Keeffe’s work.

O’Keeffe references the illuminated arches in this photo, taken by George Seward in the 1930s, in her letters. (Image courtesy Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

“I found a picture of the Rotunda at night, taken from the Chapel, where just the shapes of the arches beneath the building are lit,” he said. “In later letters, O’Keeffe talks about seeing this, seeing the light on the Rotunda and wanting to do something with it.”

Meaghan Walsh, a second-year doctoral student studying art history and architecture, noted that O’Keeffe kept her sketchbook from Charlottesville with her until her death.

“To me, that reveals the importance of her summers in Charlottesville in her career,” Walsh said. “When you look at how her style changes and develops from her first summers in Charlottesville to her last summer in Virginia, you can see her growing interest in abstraction, portraying the world around her, and attention to detail. All of these interests are apparent in her later works, which suggests that it was in Charlottesville that she developed the distinctive features of her artistic style.”

McLendon has found enough to declare the exhibition just the beginning of telling the full story of O’Keeffe’s years in Virginia. He and Turner hope to turn the exhibition into a book project with Turner’s students.

“The exhibition has opened up so many lines of inquiry,” McLendon said. “It really is the ideal university museum project, with an exhibition that will add significantly to scholarship and offers plenty of opportunities for students, who have been actively engaged in pushing that scholarship.”

He, Turner and the graduate students behind the exhibition hope it plants a flag for O’Keeffe at UVA. Chance put it this way, gesturing to the Rotunda and other nearby buildings and gardens.

“I wanted us to reclaim her. We have a significant chunk of her history. A good, solid foundation was laid here,” he said. “It started in these buildings.”

Turner also sees O’Keeffe’s story as an important reminder of the many other journeys that have and will start here on these Grounds.

“It is important for us to remember,” she said, “to know how someone can set a path and chart a course here, have a profound awakening here, that will lead them to contribute great things through the rest of their lives.”

Media Contact

Article Information

October 16, 2018

/content/virginia-years-untold-story-georgia-okeeffes-time-uva