So what exactly is Brogdon putting in his Wheaties?

In the spirit of the movie, “Bull Durham,” we weren’t about to ask him.

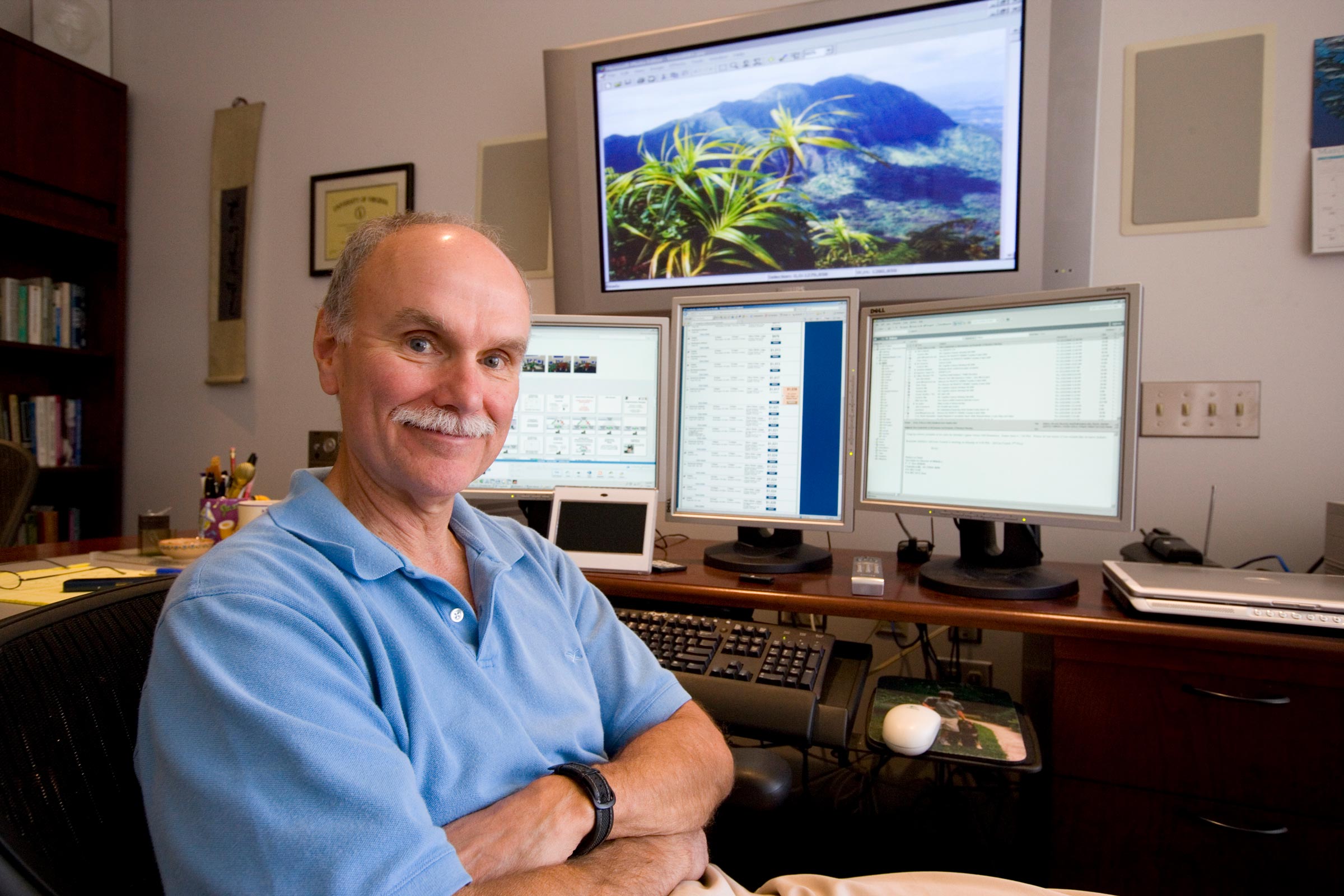

However, since it is a common belief that being a good free-throw shooter revolves mainly around practice and confidence – perhaps mixed in with a little bit of physics? – we caught up with UVA assistant men’s basketball coach Jason Williford, UVA psychology professor Dennis Proffitt and UVA physics professor Robert Jones.

Q. How do you account for Malcolm’s improvement from the free-throw line as a pro? Can you pinpoint anything?

Williford: Work ethic. The dude is a machine. He probably shoots hundreds of free throws a day before and after practice. And he’s super-confident in his basketball skills. Having confidence and then working at it makes for a pretty good recipe.

Proffitt: I have, of course, no idea why Brogdon is on this hot streak. Along with the obvious reasons – skill, practice and technique – are such psychological factors as confidence.

Perhaps of interest is the likelihood that for Brogdon, the hoop may look bigger when shooting foul shots than it does for other players. Sports’ lore is filled with observations from players that the target in their sport looks bigger when they are hitting it well. For example, once after a home run, Mickey Mantle described the ball as looking as big as a grapefruit.

Research in our lab – mostly with golf – has shown that this anecdote is real. The golf hole does in fact look bigger when golfers are putting well. I suspect that Brogdon may have an unfair advantage these days in that for him, the hoop may look as big as a kiddie swimming pool – some exaggeration here.

Q. Are there any laws of physics that come into play when shooting a basketball?

Jones: The relevant laws of physics are Newton’s laws of motion and gravity, as applied to projectile motion and collisions. The path of the projectile (i.e. the basketball) toward the hoop is determined by the force that the shooter uses to launch the basketball into the air, and gravity acting on the ball while in flight. If the ball hits the rim (or backboard) then the physics of collisions determines whether the ball will fall through the net or not.

Both the amount of the shooter’s force – which determines the initial speed of the ball – and its direction are important. Gravity is fixed, so once the ball leaves the shooter’s hand, the motion is set. Of course, the ball can reach the hoop using many different combinations of initial speed and direction, but each of these results in a different ball speed and direction of travel at the hoop. These two parameters are very important in setting the likelihood that the shot will be made.

The key to being an accurate shooter is the ability to precisely and consistently reproduce the optimum launch force.

Q. Is Malcolm doing anything different mechanically?

Williford: I watch a few minutes here and there when I can – but I’m not sure. I would imagine it’s probably the same shot. But when he was here, we wanted him to get the ball late in the game. It was like, “Malcolm, you get the ball and go make free throws.” And he wanted to go make free throws. There was a confidence of, “Just give me the ball, I’m going to make them. I shoot enough of these and have trust in my stroke.” He just trusts his free throw stroke and is confident when he gets it.

It’s amazing because you see guys that struggle at the line both in college and the pros – but they can shoot. I don’t understand it. It’s all in their head. Malcolm is just supremely confident in his abilities.

Q. Can anybody be a good free-throw shooter?

Williford: Sometimes there are mechanical [issues] and then sometimes it’s confidence – just not trusting your stroke. Certain big guys like Shaq – because his hands were so big and his mechanics – just wasn’t going to be a good free-throw shooter. But a lot of that is upstairs.

A lot of golfers can be on the practice range and drain putts left and right, but then as soon as they get into competition where there’s something on the line, it’s just a mental block. You just have to trust your stroke.

Q. Would Isaac Newton have been a good free-throw shooter?

Jones: Of course I don’t know, but assuming he was like most other scientists, he probably would have been content calculating the optimum angle and speed of release, or designing a machine that could consistently produce the precise forces required, rather than taking the many hours of repetition required to train his imperfect body to consistently produce those precise forces on demand.

.jpg)