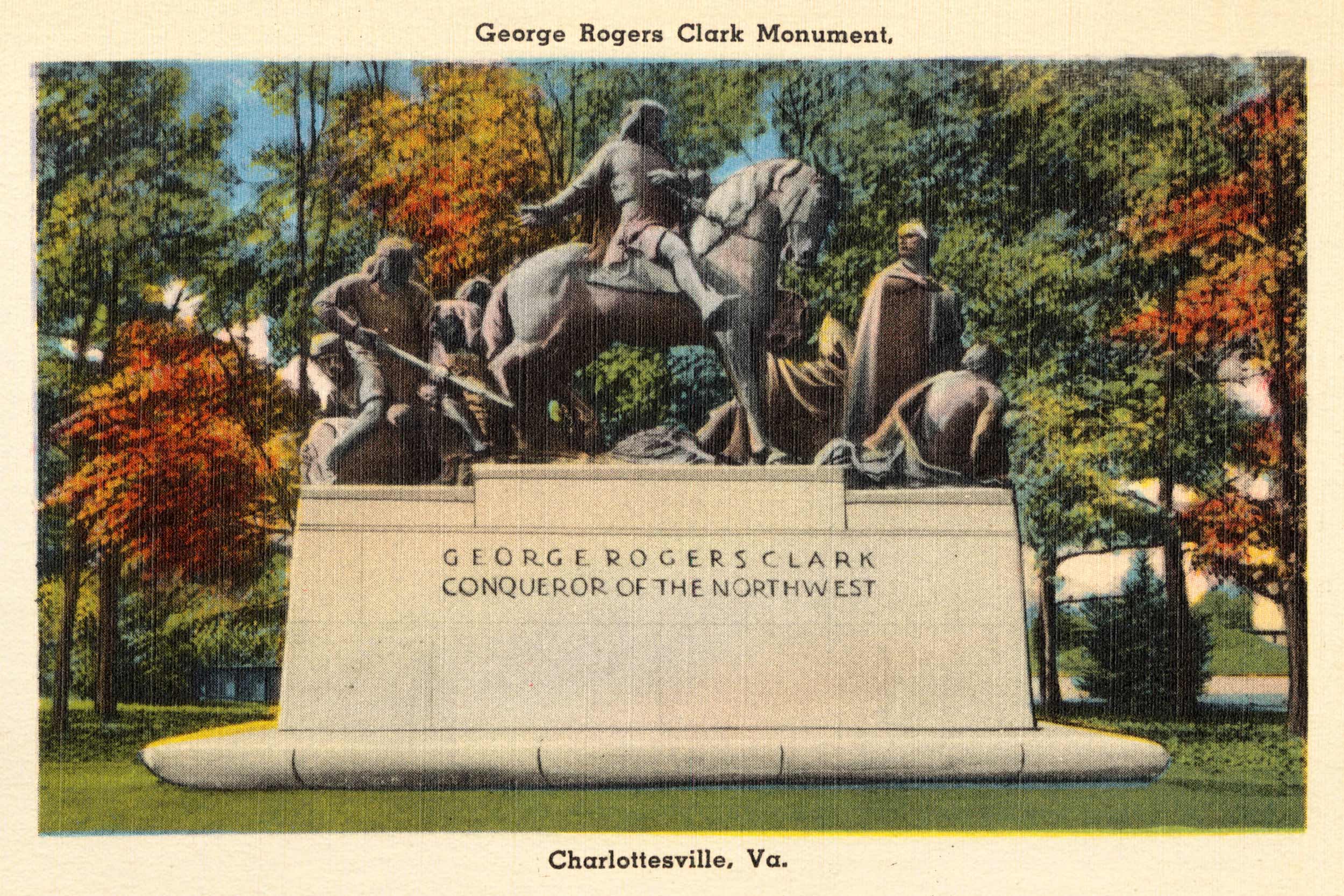

Lewis and Clark, of course, had encountered nothing like a wilderness – and they would never have claimed such a thing. Nor would Jefferson. On the contrary, Jefferson knew that west of the Mississippi, Native people were in charge. In fact, it was, according to Jefferson, the “immense power” of the Sioux, particularly the Lakota, that would be the biggest barrier to American trade and settlement.5 The wilderness that Armistead Gordon imagined in 1919 at the unveiling of the Lewis and Clark statue was in fact a region in which Sioux population and power would only increase in the decades after Lewis and Clark passed through.

In the early 1920s, in America and Virginia, worshipping those who settled the American landscape and erasing the presence – in the past and the present – of those who were here first, was commonplace. This manifested in several ways.

For one, in the decades surrounding World War I, the number of statues memorializing the settlement of the West exploded. The frontier had “officially” closed as of the 1890 census. No longer was the West considered unsettled. Frederick Jackson Turner, in his famous 1893 essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” claimed that the frontier was a place of rugged individualism, where societies could be formed anew. But with the closing of the frontier and America’s increasing urbanization, a key piece of America’s identity disappeared. When it did, a newfound interest in the country’s pioneer past emerged.

At the same time, Indians had come to be considered a “vanishing race,” doomed to extinction. Fueling this notion was a proliferation of “expert” opinion regarding what they argued was the vanishingly low Native population prior to contact with Europeans – an argument used to justify denying Native peoples legal rights to land.6

Finally, the American West was reimagined as having been a wilderness, a land uninhabited and free for the taking. The American past was rewritten and Indians were erased. There was no place to recognize, for example, the “immense power” Jefferson knew the Sioux possessed over a huge swath of the Northern Plains. The West, in this new historical narrative, was empty. The statues dedicated to Lewis and Clark and George Rogers Clark reinforced this historical narrative.

The myth-building about the vanishing Indian would not only be advanced by monuments. More devastatingly, actual laws harmed Native people and exacerbated discrimination against them for decades.

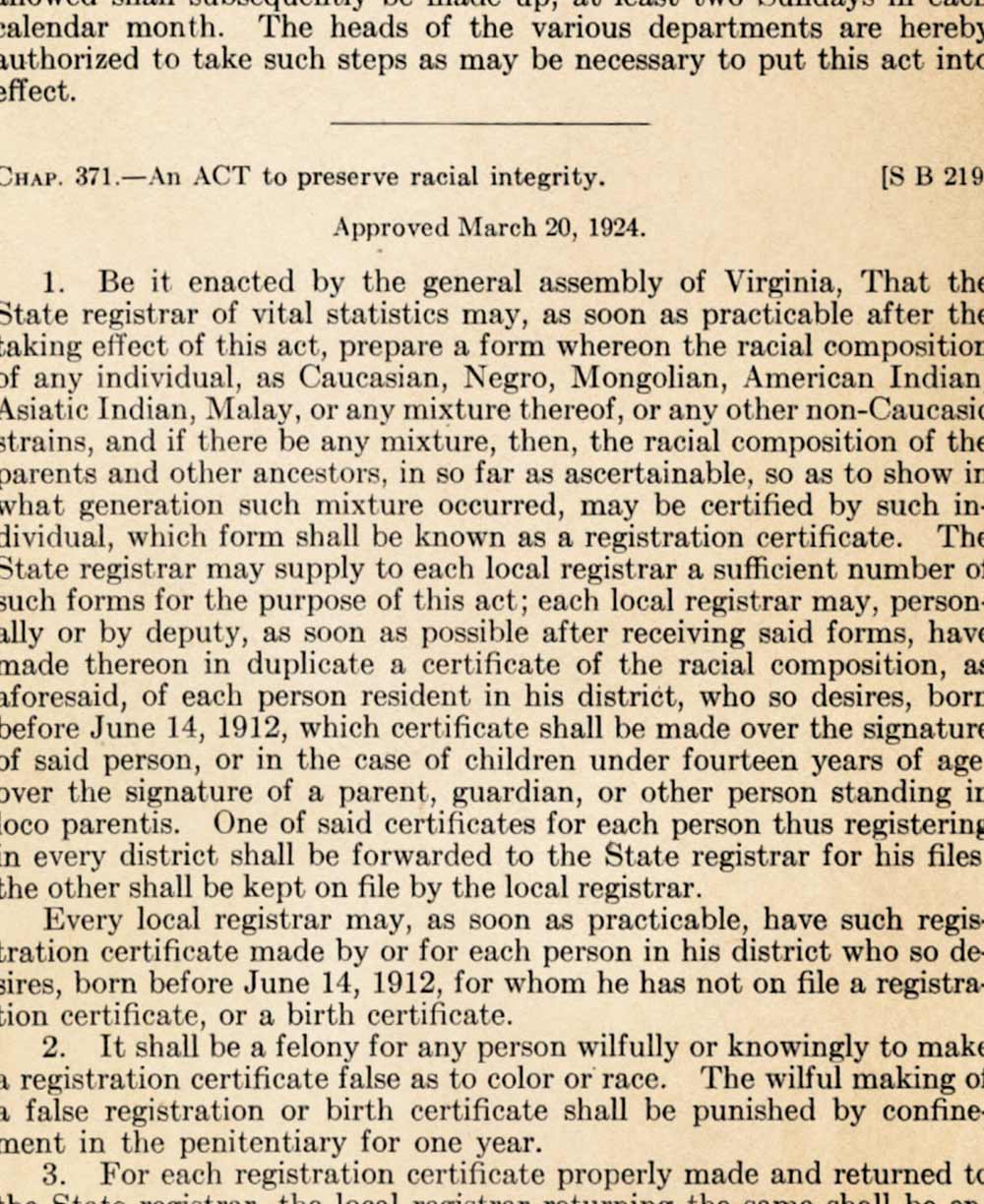

In 1924, when the General Assembly passed the notorious Racial Integrity Act, Virginia added racial purity to this already toxic mix of ideas. The act redefined racial classification in Virginia. Now, there were two: white and black. The categories were strictly defined and meticulously policed by the Bureau of Vital Statistics. Being Indian was no longer possible.

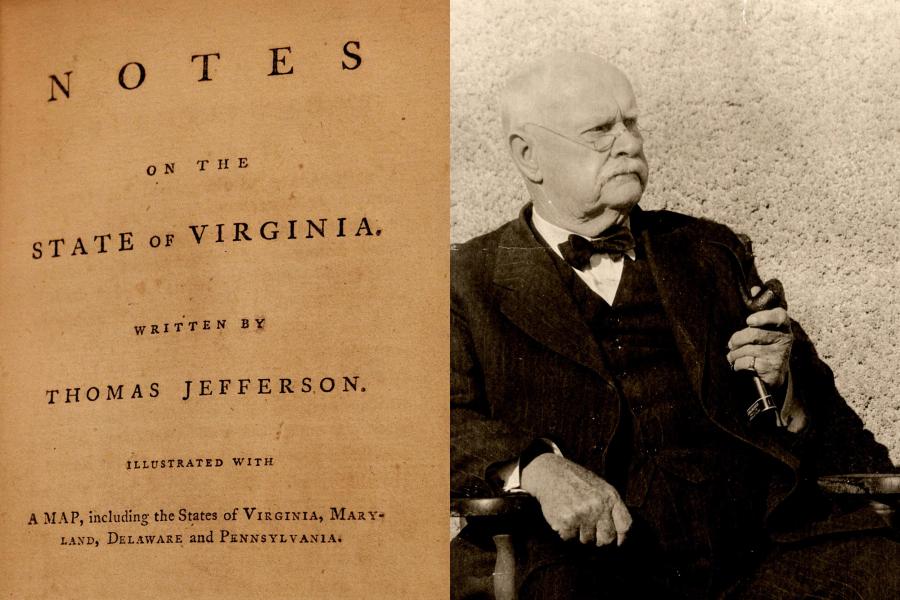

Native people in Virginia began to disappear from official records such as the census. After all, they no longer existed. By the 1940s, the Racial Integrity Act had greatly diminished the number of official Native people in Virginia. Walter Plecker, the State Registrar of Vital Statistics, was relentless in his pursuit of racial purity. He chased down individuals claiming to be Indian.7

In 1940, when explaining why he returned one man’s birth certificate, he wrote the following: “We have learned that none of the native-born individuals in Virginia claiming to be Indian are free from negro mixture, and under the law of Virginia every person with any ascertainable degree of negro blood is to be classed as a negro or colored person not as an Indian.” To another person claiming to be Indian, he wrote: “We do not recognize any native-born Indian as of pure Indian descent unmixed with negro blood. According to the law of Virginia any ascertainable degree of negro blood constitutes the individual a colored person.” Finally, after assiduous research in 1943 he claimed: “Public records in the office of the Bureau of Vital Statistics, and in the State Library, indicate that there does not exist today a descendant of the Virginia ancestors claiming to be an Indian who is unmixed with negro blood.”8 Therefore, there were no Indians in Virginia.

As the national historical narrative erased Indians, so, too, did Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act.

The impulse to pass laws like the Racial Integrity Act emerged out of the then-flourishing “science” of eugenics. Eugenics was based on the notion that, through selective breeding, superior racial stock would emerge. By forbidding the races to inter-marry, racial purity, and thus white racial supremacy, could be maintained. Eugenics, explored previously in this series, flourished at the University during the first decades of the 20th century.

During the 1920s, in addition to hiring professors who promoted eugenics, UVA also hired sociologist Floyd House. House got his Ph.D. at the University of Chicago, studying under Robert Park. He arrived at UVA the same year as Ivan McDougle and Arthur Estabrook published “Mongrel Virginians: The Win Tribe.” Win stood for “white, Indian, negro,” and the book was presented as an ethnographic-like case study of the nearly apocalyptic consequences that resulted when the races mixed. The community “Mongrel Virginians” depicted largely self-identified as Indian.

But not everyone believed in the racist logic of eugenics. Jeff Hantman, professor emeritus of anthropology at UVA and an expert on the Monacan Nation, has been doing research on House and the history of anthropology at UVA. Hantman’s research revealed a fascinating 1928 UVA master’s thesis by Bertha Wailes, one of House’s students. “Backward Virginias: A Further Study of the Win Tribe” was in many respects a rebuttal to Mongrel Virginians. Wailes knew the community well and argued that while they were indeed “backward,” their place in the social hierarchy could not be explained by their race. In fact, if race played a role in their social position, it was due to the racial prejudice of their neighbors and not any inherent racial characteristics the so-called Win Tribe possessed.

![UVA’s Clark statue held “creat[e] and perpetuat[e] the myth of brave white men conquering a supposedly unknown and unclaimed land,” though Native Americans already lived there. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications) Up close of statue text that reads: George Rogers Clarks Conqueror of the Northwest](/sites/default/files/grc_engraving_ss_inline_02.jpg)