It took an earthquake to convince one city to do away with a double-decker highway.

City planners in San Francisco had tried for years to get approval for removing the Embarcadero Freeway that blocked access to the San Francisco Bay, before a 1989 earthquake finally made that roadway unusable. (It also collapsed a section of another elevated highway in Oakland, killing 42 people.)

The Embarcadero Freeway was torn down, and the area developed into a waterfront park, attracting jobs, housing, activities and tourists.

University of Virginia engineering professor Leidy Klotz took his family to visit the Embarcadero park several years ago. While he didn’t know it at the time, it would become the opening story for his book, “Subtract: The Untapped Science of Less,” published a few months ago. He tells readers “subtraction is the act of getting to less, but it is not the same as doing less. In fact, getting to less often means doing, or at least thinking, more.”

It is more than worth it, his book reveals; applied to the world’s toughest problems and everyday life, the options of different kinds of subtraction are helpful and necessary as humans pursue a better future.

Klotz’s book has much to say about how humans came to rely on adding more, and why we should consider taking away to solve problems. To illustrate, he describes a range of ideas from concrete examples – including the invention of a new building block – to abstract concepts and dilemmas, like racism and climate change.

Klotz brings together many of the reasons why subtracting might be a more successful option or strategy and conveys them through lively stories from science, history and daily life. (Photo by Tom Cogill)

He brings together many of the reasons why we need to be reminded that subtracting might be a more successful option or strategy and conveys them through lively stories from his life at home – he and his son playing with Legos, for instance – to involving students in subtraction studies, to ancient history, including the early construction of temples.

Klotz, the Copenhaver Professor in the Department of Engineering Systems and the Environment in UVA’s School of Engineering, said he hopes the book will help readers “rearrange their mental furniture” to make them more likely to think about subtraction.

In addition to his own reading and research, Klotz, who also has joint appointments in the School of Architecture and Darden School of Business, worked with colleagues and students across disciplines conducting experiments to see whether people would recognize when taking away would be a better option. His collaboration with professors Gabrielle Adams and Benjamin Converse of the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy was supported by a 3Cavaliers grant and resulted in a paper published (and featured on the cover) in April in the journal Nature (covered in a previous UVA Today article), which also served as the basis for Klotz’s first chapter.

“That finding – that people systematically overlook subtractive options – raises two questions: ‘Why don’t we choose it?’ And ‘What can we do about that?’ We’re missing out on a basic way to make the world a better place,” Klotz said, adding, “How can we do better?” Considering both addition and subtraction, instead of just the former, should be the goal, he said.

Klotz said his motivation for all his work, the book included, comes from wanting to make the environment more sustainable, to allow more people to thrive, now and in the future. He had long noticed how the mindset to keep adding, thinking that “more” is always better, seemed to be a root cause of problems like climate change. His breakthrough came when he homed in on subtracting as an action. And that action, it turns out, isn’t easy.

“Removing a freeway is far more challenging than leaving it alone, or than not building it in the first place. As my team would find in our studies, mental removal requires more effort, too,” he wrote in his introduction.

Klotz said he was drawn to UVA because of its support for interdisciplinary work, with the leadership and faculty in the departments he joined in 2016 particularly supportive of a boundary-crossing exploration of the science of people and things, which he credits with nurturing his work that combines psychology with how we create and build things.

“I moved to UVA to be able to do this work, and it has been the perfect place for it,” Klotz said.

“Subtract” is receiving widespread media attention, but Klotz said the best kind of feedback is like that he got recently from an incoming first-year student who was inspired after she read it.

“I was intrigued by your interdisciplinary work in cognitive science and engineering,” Caroline Wynne, who hails from Seattle, wrote in an email. “The past few years I’ve developed an interest in cognitive science and the relevance it poses to many other fields. I thought it was so cool to see someone (at UVA no less) using behavioral science to address a wide variety of fields and systems.”

Klotz involved his students in several experiments conducted at UVA, one of which looked at whether patent documents used adding or subtracting language in describing innovations. Doctoral student Katelyn Stenger and Clara Na, at the time a second-year undergraduate student, carried out the study, finding that patents contained three times more additive terms than subtractive ones.

Klotz also shared his ideas when he taught an architecture seminar on “Positive Subtraction” in 2019.

He’ll resume teaching in person this fall, in a large engineering and architecture course, “Behavioral Design,” open to any UVA student. (At a basic level, we all are “designers” any time we change something from the way it is to what we want it to be, he explained.)

Included here from “Subtract” is a checklist – or a “lesslist,” that Klotz provides as a process for readers to use subtraction.

The “lesslist”

Subtract before improving.

Sometimes, when there’s a lot of information or things happening at the same time, subtracting details can help to find the essence in a system. Hospital emergency room personnel use the triage process to determine who needs care the quickest, asking three questions: Does this patient require immediate lifesaving intervention? How many resources will this patient need? What are the patient’s vital signs?

The doctors and nurses still need to have the huge store of medical knowledge they’ve learned, but focusing on fewer steps enables them to make decisions that lead to better care of patients.

Make subtractions first.

Klotz describes the game of Jenga as an example that also emphasizes balance. Players must take away pieces of a tower made of wooden blocks and arrange them on the top without toppling the tower. Sometimes in planning a project, taking away can subvert problems that might emerge down the line.

In a common parenting situation, Klotz describes that when it came to play time with an iPad, instead of giving his son an incentive – getting a cookie – to not use it, he found it was better to remove the iPad as a choice.

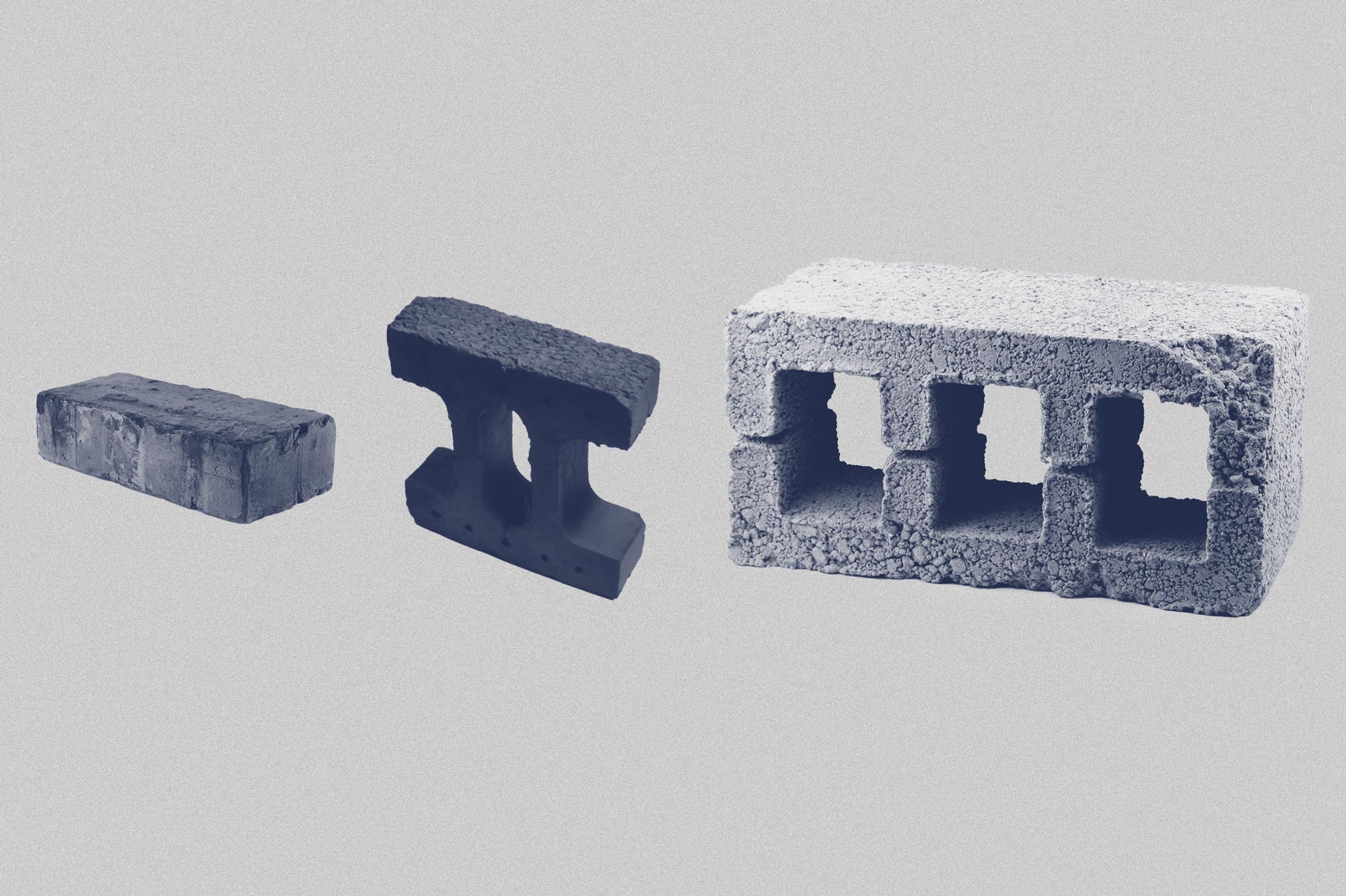

Subtractions can be efficient, too. Anna Keichline, an early 20th-century architect, is credited with designing the precursor to the concrete block. Her 1927 patent subtracted some of the inner mass of the building block, leaving the load-bearing outer parts. The hollow block required half the material to make, so was less expensive, and provided some insulation as well.

Persist to “noticeable less.”

This idea explores how it can be tricky to show that subtracting something has produced a better product – with writing being a good example. Strunk and White’s “The Elements of Style,” still found in more courses than any other writing guide, advises “omit needless words,” but Klotz’ collaborative research at UVA showed that people tended to add, rather than subtract words when working with content. Writers and readers need reminding that the guidance results in stronger writing, he said.

Because we often can’t see what’s been taken out, Klotz looked for examples where what had been removed made something stand out. That could be getting rid of the double-decker freeway in San Francisco, but also is noticeable in Bruce Springsteen’s stripped-down lyrics and instrumentation that were the defining feature of his “Darkness at the Edge of Town” album, Klotz said.

Reuse subtractions.

Can you say doughnut holes? They’re a nice reminder of the commercial use of what’s left over. Klotz retells the two parts of the story: that in the mid-19th century, dough was cut out of the middle to improve the frying and the flavor. It took more than 100 years for someone to think of making and selling those small bits as bite-size pastries.

In another example of using subtraction to improve a system, Klotz describes how the protests against apartheid that were most successful drove divestment in South Africa. The actions of taking away the financial support put pressure on the government to dismantle the unjust system. Plus, the financial support that was removed from apartheid could be reinvested elsewhere.

Media Contact

Article Information

August 5, 2021

/content/4-ways-use-subtraction-could-make-life-better