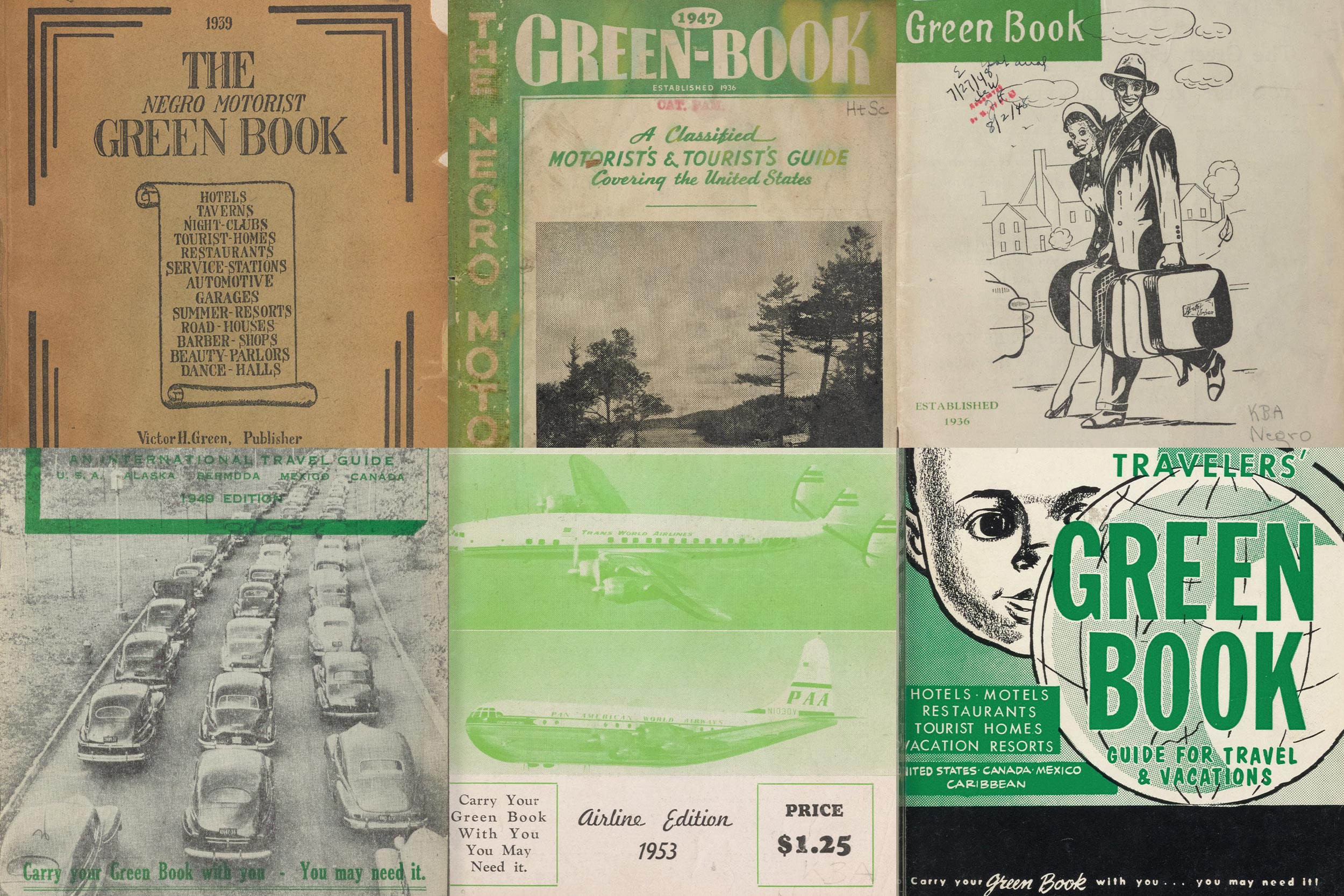

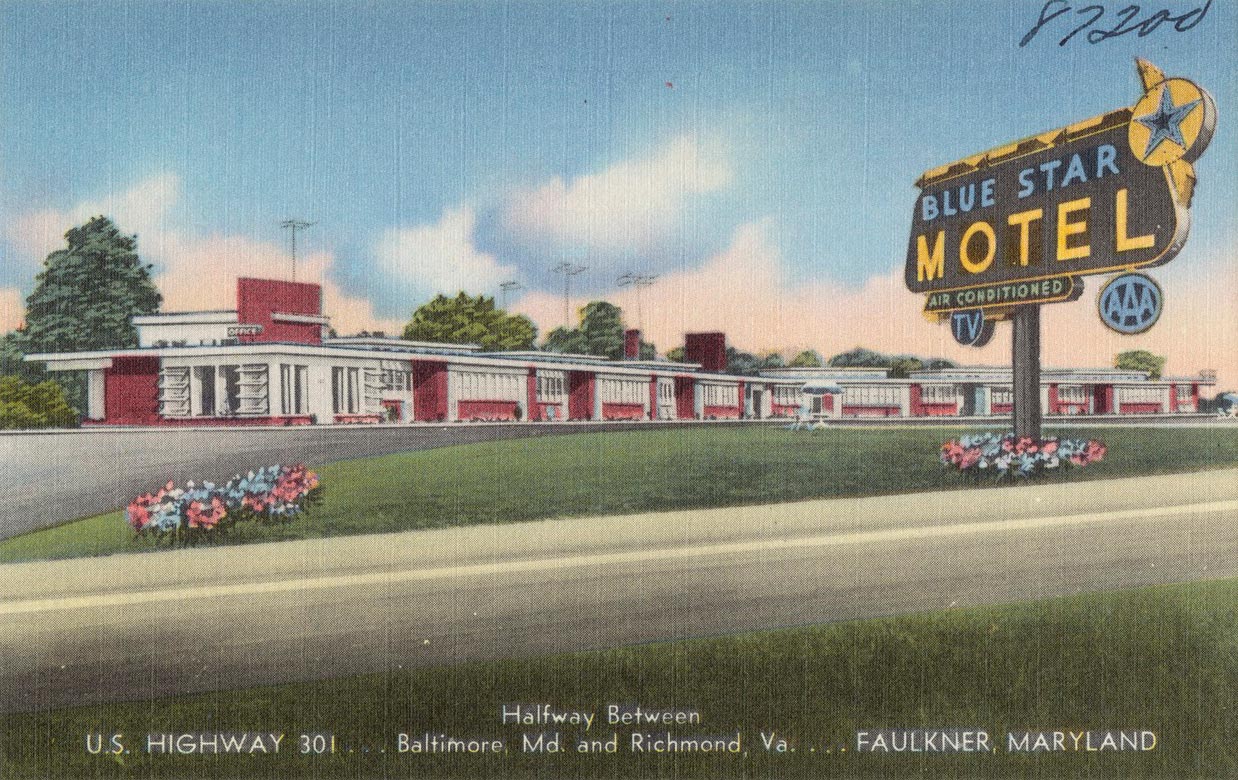

The guides reveal part of 20th-century U.S. history and how African Americans tried to avoid racism on the road. By its final year, the Green Book covered all 50 states and some foreign destinations. The books, organized by state and city or locality, recommended hotels, restaurants, gas stations, places for recreation and other services that Black travelers could rely upon, including accommodations that were sometimes in people’s homes.

From 2016 to 2020, Hellman had visited almost every place in Virginia with Green Book listings, checking on what happened to the establishments, and yet she fears that these sites are already disappearing.

“Since I started driving all over Virginia to document these, I know for a fact that some that were standing when I photographed them are now gone,” wrote Hellman, the principal planner for the city of Alexandria, in an email. “Two, for example, are the Colbrook Inn, south of Petersburg, and Bob & Sam’s Drive Inn in Newport News. [Over its 20 years, the Colbrook was also called a motel at one point.]

“In the case of the Colbrook Inn, they will at least retain the sign, and the site will be used for a good purpose” – to build a new affordable community housing development.

For Hellman, her primary goal for this project “is to raise awareness of these sites and therefore protect them. I nominated Virginia Green Book sites to Preservation Virginia’s 2021 Most Endangered Historic Places, noting that there are over 300 sites, so I realized that this was an unusual entry. But Preservation Virginia thought it was a great addition to the list.”

Despite having different kinds of day jobs in different states, the three architectural historians are on a mission: “Our goal is to build a database that tracks what happened to all of the sites that were ever listed in all of the Green Books,” Zipf wrote in email, “so, a small task,” she joked.

The team is recruiting scholars from all 50 states, including possibly many graduates of UVA’s Department of Architectural History, to document which buildings and sites across America have survived – or not, showing their fates on a single, searchable online platform.

Nelson, whose research has explored historic architecture in settings from the Academical Village to Jamaica, emphasized the significance of this project, saying, “The Green Book offers an extraordinary window into the landscapes of racism and resistance across mid-century America.”

“This project differs from others on the Green Book because it focuses on buildings and architecture,” Nelson said. It will become “a resource for state preservation offices as they are doing the work to recover important African American sites that have been overlooked because of the way history and historic preservation have been practiced in the U.S.”

Worthy Martin, director of the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities, observed that the website is based on an architectural history perspective – that is, “it is not focused on the published issues or on the people involved (although it will certainly address both), rather it is focused on the buildings and the architectural context,” he wrote in email.

Zipf, who serves as the executive director of the Bristol Historical & Preservation Society in Rhode Island, was writing a monthly column on architecture for the Providence Journal, when she saw a notice in 2015 about the Green Books; The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library had digitized its nearly complete collection.

“I posted a link to the article on my Facebook page, which is how Anne saw it,” Zipf wrote in email. “She read it and, having spent many hours researching African American architectural history in Maryland, proposed we do more with the topic.”

Bruder first found out about the Green Book when her book club read “The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration,” by Isabel Wilkerson, three or four years after its 2010 publication, she wrote in email. “It mentions the Green Book being used by one doctor as he moved from Louisiana to California in the 1950s, and that started my interest about what buildings had been included in Maryland and if they still existed,” Bruder said.

“Catherine’s article got me to go look at buildings (I work for the Maryland Department of Transportation State Highway Administration, so I’m a ‘road scholar.’) Since we’re architectural historians, our interest is always in the buildings and how they help tell the story of a place.”

Zipf and Bruder submitted a poster session proposal to the Southeast Chapter of the Society of Architectural Historians. “Things snowballed,” Zipf said. “People who were either already working on the Green Book, or wanted to, kept coming out of the woodwork. At this point, Anne and I reached out to Susan to see if she was interested in working on Virginia, which she was.”

At the chapter’s conference in fall 2016, the trio presented an overview poster and five posters about Green Book locations in Rhode Island, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina and Mississippi.

“Starting with five posters, our rag-tag band of architectural historians has completed or begun work on approximately 20 posters,” Hellman said. “We exhibit them at conferences and lectures and plan to create posters for each state.”

“At this point we’re thinking of them as places of resistance during segregation,” Bruder said. “And every state in the country had some sort of segregation law, so it wasn’t confined just to the former Confederate states or the South, but included Rhode Island as well as Washington state and Alaska.

“What interests me about the project is that it’s a lost piece of history,” Bruder said. “We can talk about slavery and the civil rights movement, but people forget that the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision in 1897 created segregation and that changed the way people were treated and could daily move about.”

Zipf said that Martin and the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities have been instrumental in the collaboration to design a flexible database structure to accommodate “all the different permutations of the research (as well as all the scholars).” Nelson helped the alumnae form an advisory committee and has been very supportive, she said. “With Louis and Worthy on the team, we are really looking forward to seeing the database come together.”

Looking to the future, Zipf said: “We’re also hoping that our information can be used to seed many other projects and, importantly, preservation efforts. We are finding that many of the sites listed in the Green Book have been demolished and that many preservationists are looking to save what’s left.

“We also hope to promote scholarship on African American architectural history and on African American travel – we’ve seen lots of scholars already doing some really good work on the topic, and we think our database can foster their efforts. And we’d really like for our database to be useful to those interested in researching their own history and for those who might have information on sites through their family lore to feel comfortable contributing to our efforts.”