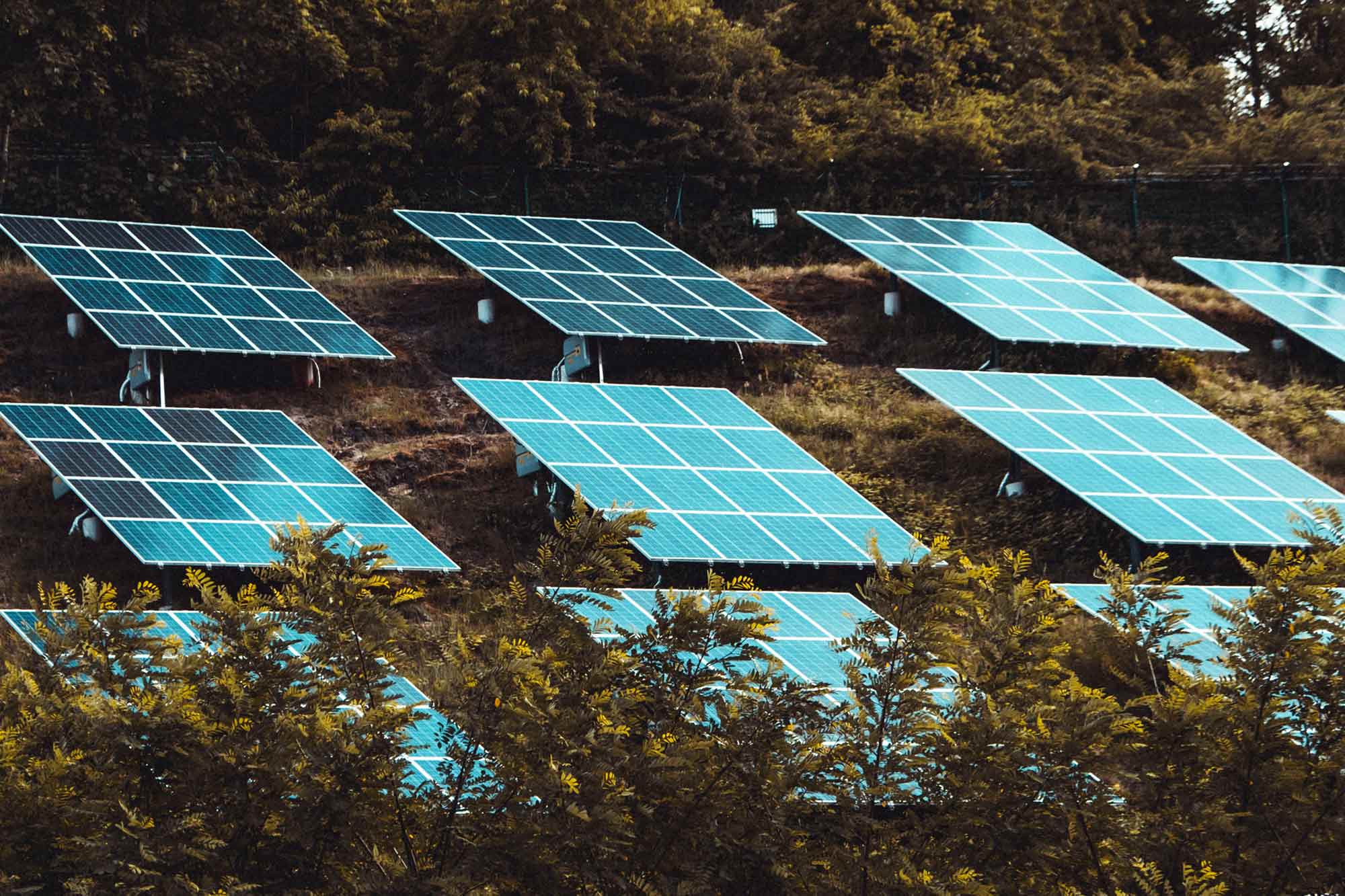

Forget the old rallying cry “There’s gold in them thar hills.” Silver, a precious metal in precious short supply, is up on the rooftops.

A research project at the University of Virginia aims to prove there’s a better way to extract the silver from old solar panels in order to put the valuable material back into new solar panels, and biomedical devices and other productive uses.

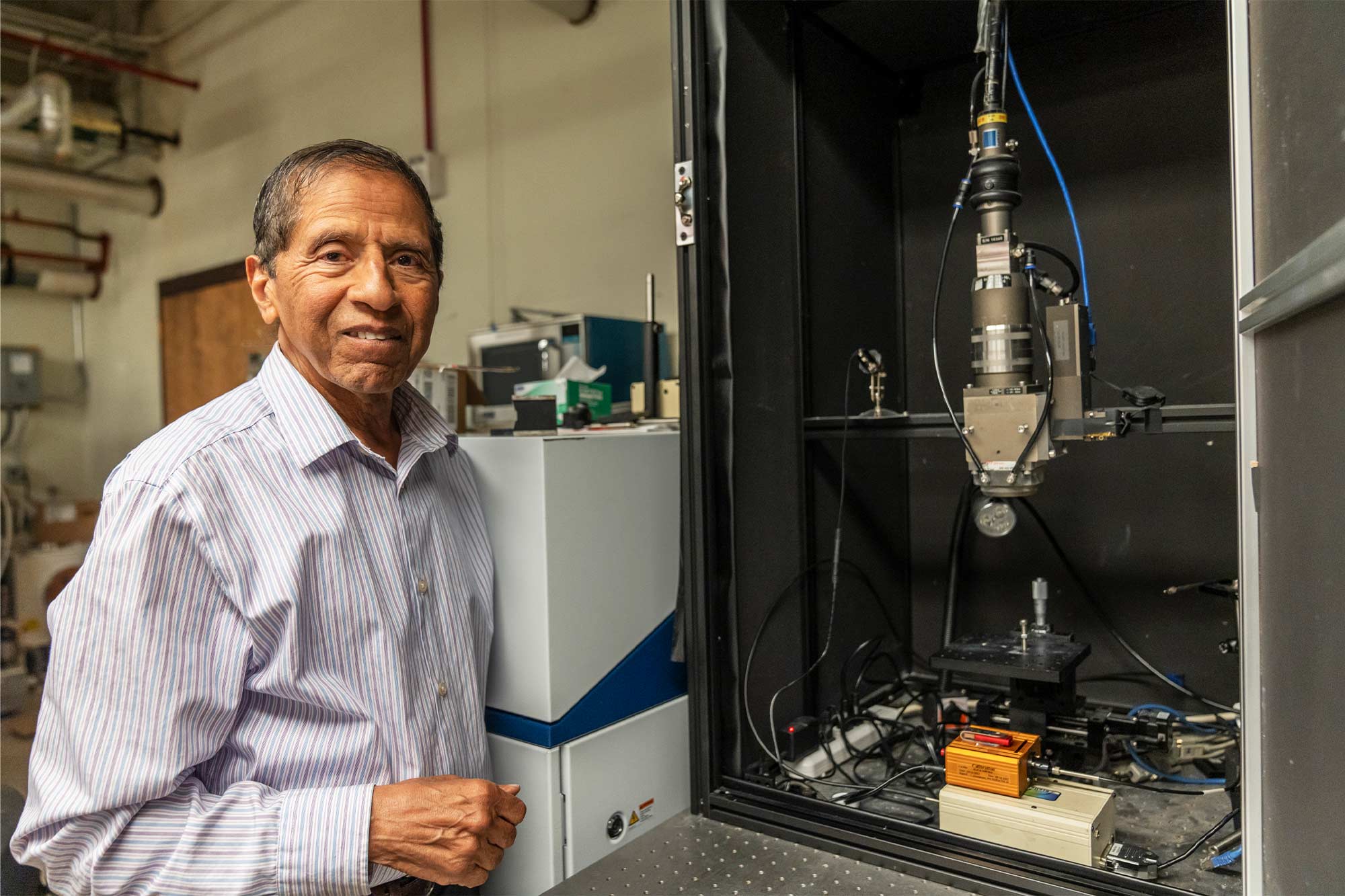

UVA engineering professor Mool Gupta is the principal investigator for the project, which received a one-year, $250,000 Department of Energy grant in June. The project is part of an overall $6 million DOE Solar Energy Technologies Office effort to seed small, innovative projects in photovoltaics and solar-thermal technologies.

“Silver is the world’s most efficient and cost-effective electrical and thermal conductor,” said Gupta, who serves as Langley Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering. “An average solar panel of two square meters in size uses about 20 grams of silver, so the photovoltaic industry consumes about 8% of the world’s silver supply annually. Yet the relative expense and demand for silver, especially in the growing solar panel market, makes it an important material to reclaim and not waste.”

When manufacturers produce panels, they prepare a silver paste, then use the screen printing process and high temperatures to make the thin silver lines that can be seen on the outside of the panels’ photovoltaic cells.

To remove the silver, Gupta said, UVA will use a new method called laser ablation on the PV cells, converting the silver electrical contact material into nanoparticles.

After extraction, the silver will need no further refinement before it can be used in new silicon modules.

It could also be purified for other uses.