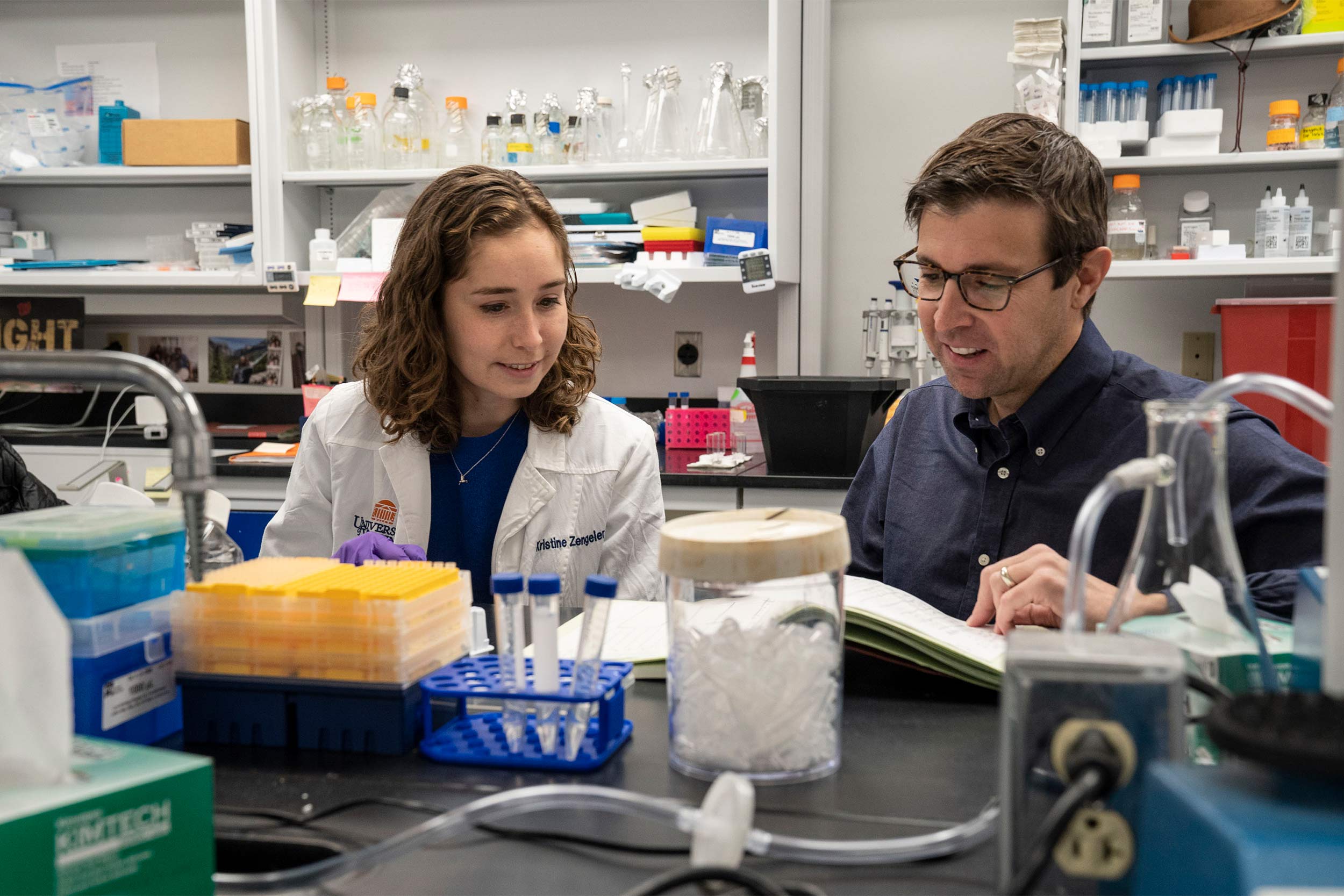

“We identified inflammatory signatures in the placenta that correlated with neurologic changes in the adult offspring of mothers that encountered an immune challenge during pregnancy,” said researcher Kristine Zengeler, the first author of a new scientific paper outlining the findings. “These signatures could be used to help identify biomarkers and druggable targets to help mitigate neurodevelopmental consequences of prenatal environmental stressors, like an immune response.”

Prior research has shown that infections, autoimmune disorders and other conditions that alter a mother’s immune state during pregnancy can affect neurodevelopment. SSRIs, the UVA researchers believe, may be interacting with that inflammation and amplifying it, leading to permanent brain changes.

The results make sense, the researchers say, because of how SSRIs alter serotonin in the body. Serotonin is an important mood regulator. It’s often thought of as a “feel good” chemical in the brain, but it’s also a vital regulator of the body’s immune response. Developing infants receive serotonin only from their mothers via the placenta in the early stages of pregnancy, so disrupting serotonin levels in mom may have consequences for baby as well.

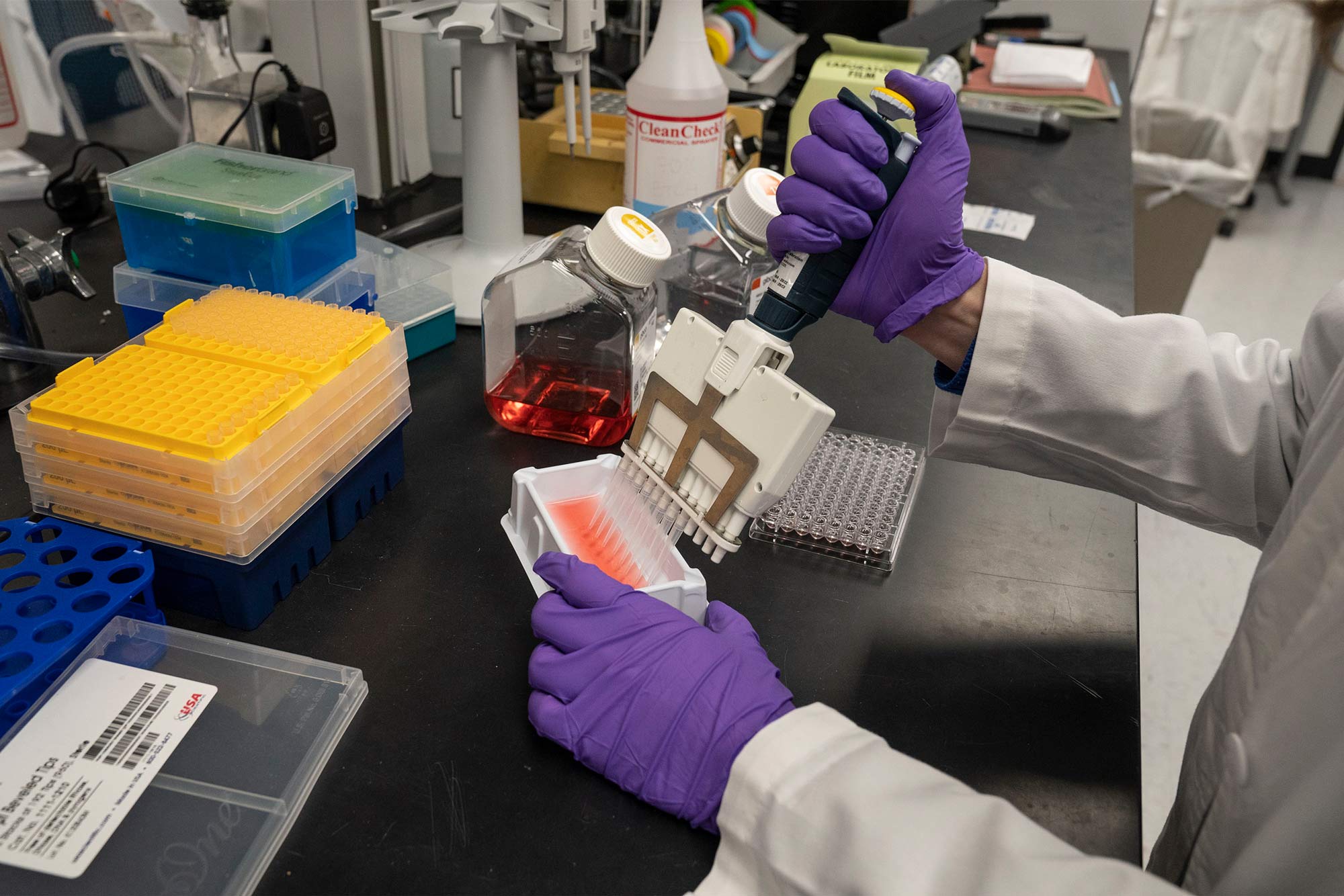

The researchers found that inflammation alone, and in combination with SSRIs, altered serotonin levels in the placenta in opposite directions. “We found that mothers who encountered an immune challenge during pregnancy showed a totally different signature in the placenta when they were on SSRIs compared to mothers that were not on SSRIs,” Zengeler said. “This highlights the importance of considering the entire prenatal environment, as drugs designed to dampen inflammation may lead to unanticipated consequences on the baby if they are combined with other modulators, such as SSRIs.”

The researchers noted that SSRIs are important tools for managing depression and emphasized that pregnant women should not stop taking them without consulting their doctors. Instead, the scientists are calling for additional studies, eventually in human subjects, to determine how the drugs may affect mother and child and to better understand the interactions of SSRIs and inflammation.

“Untreated maternal stress, depression and anxiety can all on their own perturb offspring neurodevelopment, contributing to adverse behavioral and cognitive outcomes,” the researchers write. “It will therefore be of utmost importance to consider both the relative benefits and potential consequences of SSRIs as a therapeutic option during pregnancy.”