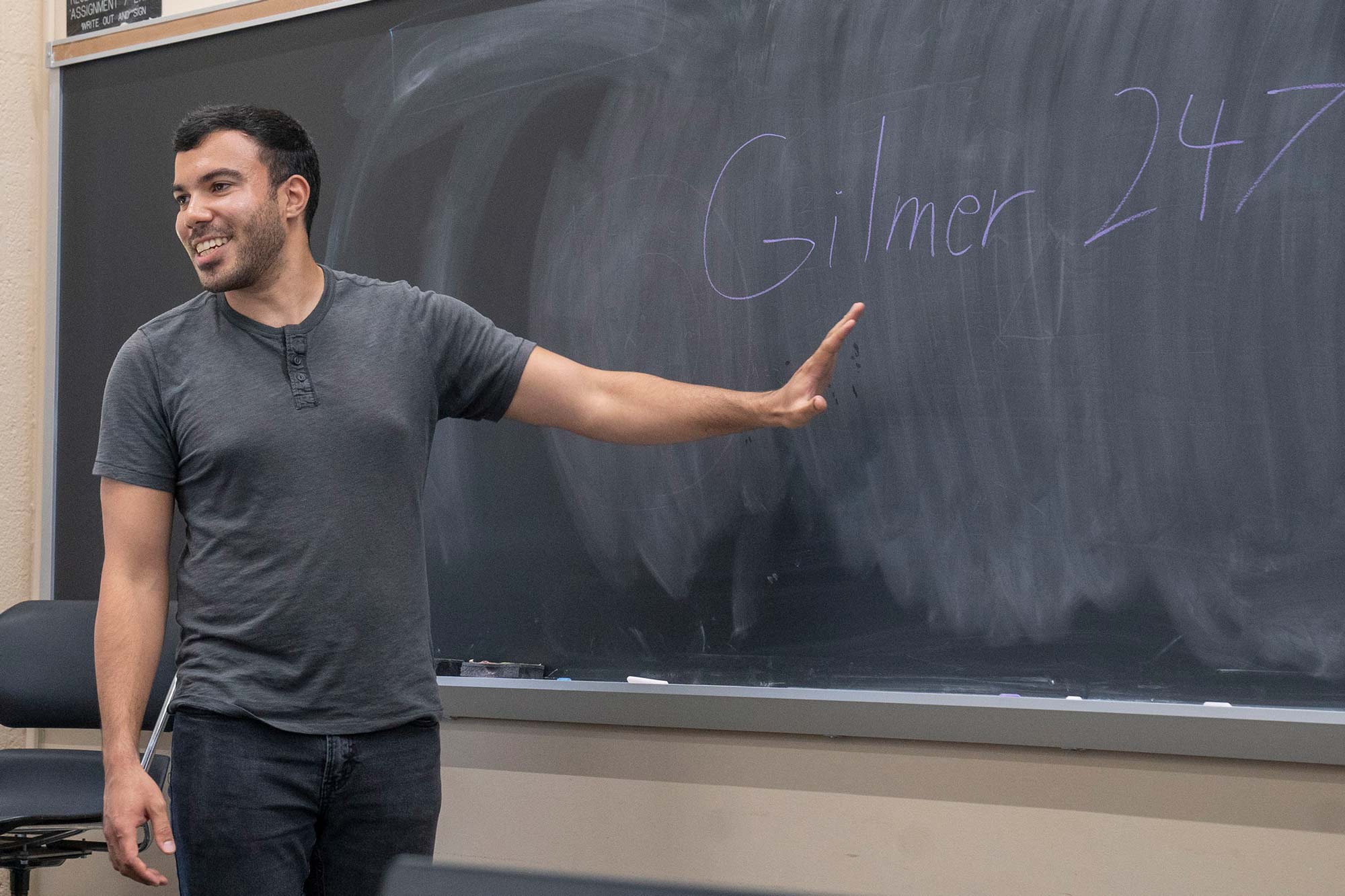

Nicholas James explores the universe in a black T-shirt and jeans.

James teaches the University of Virginia summer session course “Unsolved Mysteries of the Universe” – intended for non-astronomy majors – that tackles compelling popular science topics.

“When people find out you’re an astronomer, they want to know about dark matter, what happens inside a black hole, are there aliens out there,” James said. “This course allows us to explore some of those fascinating concepts in a way that’s accessible to really anybody.”

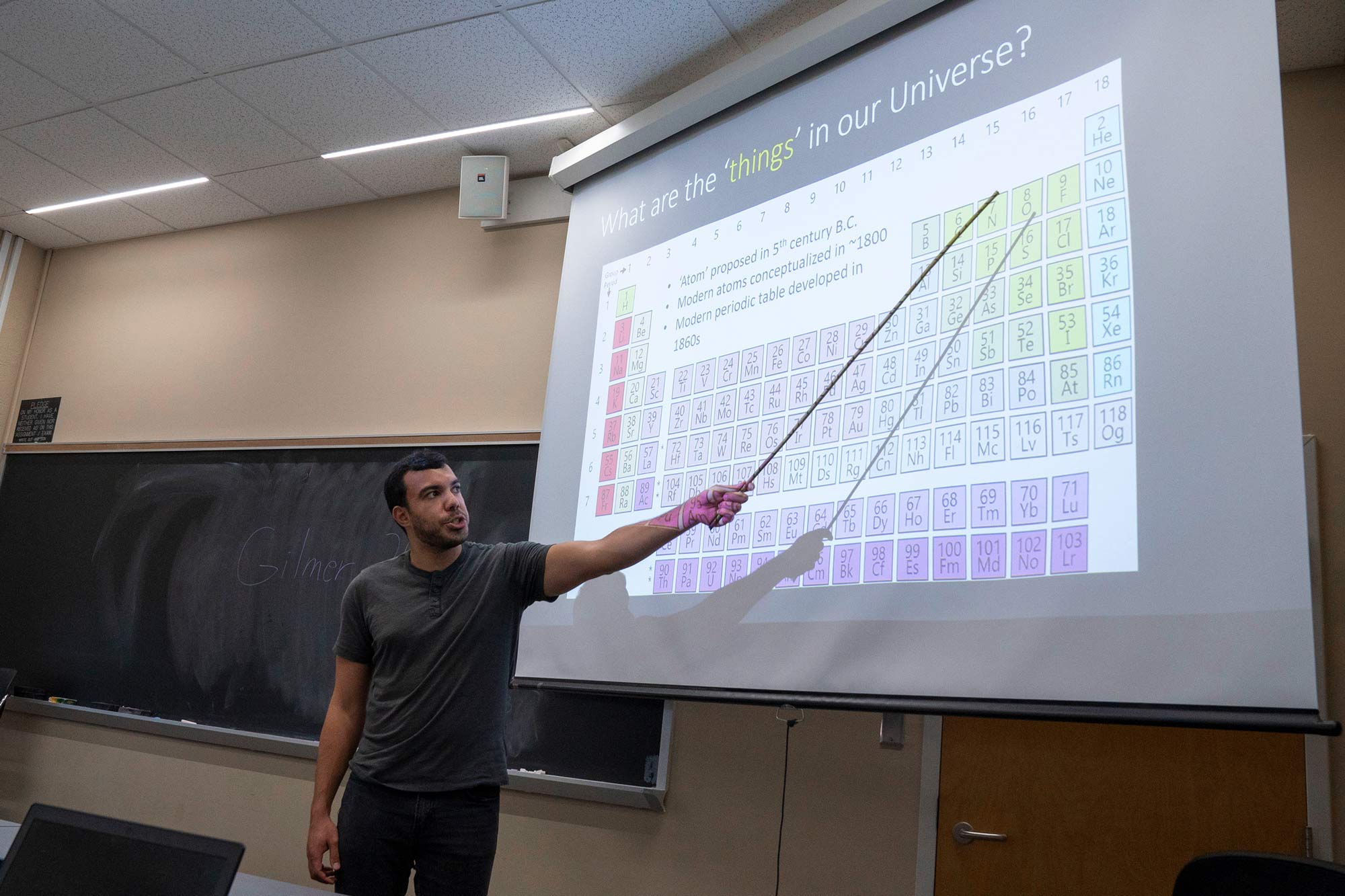

James, who is completing his doctorate, took over the course originally started by professor Kelsey Johnson and taught it the past two summers. The course’s content has morphed over the years depending on the instructor, James said, who said he is stressing the “nuts and bolts” of the cosmos. That means probing the fundamentals of astrophysics, understanding gravitational processes of how solar systems interact and how to detect planets outside our solar system.

In a recent class, James spent the two hours moving back and forth in front of the room, explaining the building blocks of the universe to about 15 students, gesturing to emphasize points. He took a brief foray into the physics of the universe to explore protons, neutrons and electrons, the basic building blocks of matter. On that foundation, he built up to bigger concepts, such as quantum mechanics and gravity.

“I think the balance is important, but we want to have a ‘wow’ factor,” James said. “Such as, here’s a picture of a black hole, here’s what happens when you get close to a black hole and the spaghettification, effectively stretching until you get pulled apart. That kind of thing gets people excited.”